Britain has not always been reluctant to countenance European unity. Tommaso Milani (LSE) recalls the intellectual impetus for a European community in the inter-war period, which was driven by a desire for peace and, from some, the left-wing case for a socialist European economy.

Britain has not always been reluctant to countenance European unity. Tommaso Milani (LSE) recalls the intellectual impetus for a European community in the inter-war period, which was driven by a desire for peace and, from some, the left-wing case for a socialist European economy.

As history is written and rewritten in constant dialogue with the present, Brexit is likely to affect the way Britons think about their national past. Due to current events, some of the interpretations of the relationship that the UK has had with the European Communities from 1950 onwards will undergo close and renewed scrutiny. Perhaps future research will finally dispel the aura of historical inevitability that surrounds Britain’s pursuit of EEC membership – which is how the story has often been presented in textbooks and surveys for the general public.

The task of the scholars operating in this field – to quote a witty analogy coined by Wolfram Kaiser – may no longer resemble “that of a pathologist concerned with identifying the syndromes responsible for Britain’s dysfunctional behaviour”, the latter being “the abnormal detachment” from the European project following the second world war. Writing in 2019, the assumption that Britain’s fate lies, and supposedly always lay, in Europe looks increasingly questionable. Long gone is the belief, so widespread in the 1970s, that the decision to join European institutions had become, in the words of Frederick S Northedge, “natural and perhaps inescapable” and only the “faulty perceptions, anticipations and priorities” of successive post-war cabinets prevented the country from embracing its preordained destiny earlier.

However, even revisionism has its dangers – the biggest of which is to further downplay the already neglected role that ideas of European unity played in British history and culture, hence fuelling a narrative of separateness and estrangement. Scholars must resist the temptation to conflate the aloofness that the British political class occasionally displayed towards institutional endeavours aimed at fostering European integration with a general lack of interest in blueprints for a federal Europe. While it is true that British leaders – especially when serving in office – have been scarcely receptive to ‘Europeanist’ intellectuals and societal pressure groups, those inputs nonetheless existed and drew heavily from a long-standing tradition of a distinctively British – as well as imperial – international thought.

If we move beyond the examination of the European policies actually put in place and incorporate a wider range of elite-level discourses on Britain’s position towards the Continent in our analysis, the thesis according to which supranationalism is a fundamentally non-British, or even anti-British, idea appears utterly untenable. As a consequence, the more we scratch beneath the government level, the less persuasive the exceptionalist accounts – based on an allegedly unbridgeable gulf between British and European attitudes towards national sovereignty – seem to be.

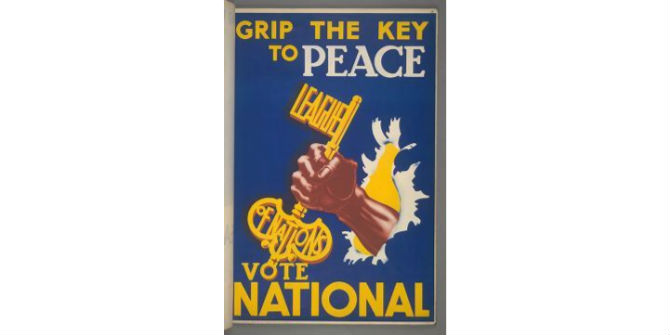

To be sure, even when sceptical or semi-detached, British intellectuals of the 19th and 20th centuries could hardly ignore the significance of Europe as a political arena – partly because of its geographical proximity, partly because the rise of the British Empire led them to focus on international relations as a distinct area of inquiry. After 1914, it was the problem of peace that came to dominate British thinking about the Continent – and understandably so, considering the sheer loss of life that the first world war wrought on the UK. While British policy promoted the creation of a relatively loose League of Nations, prominent voices contended that only the centralised pooling of armaments, rather than a non-binding legal framework for member states, would prevent the outbreak of wars in the long run. The trajectory of Philip Kerr – a distinguished politician, editor, and diplomat better known as Lord Lothian – from critical backer of the League to advocate of European federalism through a prolonged flirtation with appeasement epitomises the painful process through which growing sections of the British establishment called into question the sustainability of the 1919 Versailles settlement.

A second, original source of support for the creation of a European federation involving Britain came from left-wing thinkers who, during the Great Depression, highlighted the danger that the drive towards greater capital concentration, economic nationalism and autarchy would exacerbate international tensions. Rather than simply championing the restoration of liberal free trade, authors like Henry Noel Brailsford, Kingsley Martin, and Leonard Woolf envisaged a European federation centred on wide-ranging economic planning, aimed at ensuring full employment, monetary stability, equal living standards between different European regions, and – perhaps more crucially – a unique sphere of influence for British socialism, which they regarded as different both from American unfettered capitalism and from the Soviet, more authoritarian brand of it.

Acknowledging the existence of a substantial body of imaginative, highly sophisticated and at times surprisingly far-sighted literature on European unity produced by British intellectuals before 1945 should not, however, be taken as conclusive evidence of Britain’s inherent European vocation. Rather, it should encourage historians to investigate how, in many respects, the peculiar, historically contingent form of European integration experimented from 1950 onwards – i.e. the Monnetian, functionalist undertaking centred on sectoral integration and aimed at achieving increasingly close interdependence between member states – was poorly suited to meet the expectations, the interests, and the demands that British supporters of European unity had expressed during the previous decades.

Researchers may come to realise that an even more profound mismatch emerged between the neat, highly stylised but deeply coherent British models of European federation elaborated throughout the interwar period and the complex, muddled, and inevitably haphazard set of institutional arrangements through which the actual European Union was gradually built. Nevertheless, British visions of European unity deserve better consideration – not only as a repository of ideas, but also as a reminder of the roads not taken by the process of integration.

If, as the convulsions of Brexit suggest, Britain’s relationship with Europe is bound to remain problematic, unresolved and impervious to any teleological reading, one could only hope that greater engagement with British ideas will stimulate Europeans to reflect more critically about the EU – its achievements, its shortcomings, and its future prospects.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Further reading and references

M. Beloff, Britain and European Union: Dialogue of the Deaf (Basingstoke: Macmillan 1996)

D. P. Billington Jr, Lothian: Philip Kerr and the Quest for World Order (Westport: Praeger 2006)

M. Burgess, The British Tradition of Federalism (London: Leicester University Press 1995)

M. Gilbert, ‘The Sovereign Remedy of European Unity: The Progressive Left and Supranational Government, 1935–1945’, International Politics (46:1 2009)

J. Frankel, British Foreign Policy, 1945-1973 (London: The Royal Institute of International Affairs 1975)

W. Kaiser, Using Europe, Abusing the Europeans: Britain and European Integration, 1945-63 (Basingstoke: Macmillan 1999, 2nd ed.)

T. Milani, ‘Retreat from the Global? European Unity and British Progressive Intellectuals, 1930-1945’, International History Review, January 2019, 1-18.

T. Milani, “From Laissez-Faire to Supranational Planning: The Economic Debate within Federal Union (1938-1945)”, European Review of History / Revue européenne d’histoire, (23:4 2016), 664-685.

F. S. Northedge, Descent from Power: British Foreign Policy, 1945-1973 (London: George Allen & Unwin 1974)

Dr Tommaso Milani is a Guest Teacher of International History at the LSE and a stipendiary lecturer in Modern European History at Balliol College, Oxford.

Good to be reminded how British attitudes to the EU have changed over time, swinging wildly between europhobia and europhilia.

I am old enough to remember the 1970’s, when there was almost universal agreement in the UK that the UK had “missed the boat” with regard to the Common Market, partly because of General de Gaulle, and had to join the Common Market as soon as possible. The UK was the “sick man of Europe”, with France, Germany and Italy all embarrassingly racing ahead of the UK in terms of economic progress.

As a passing note, I notice the reference to LSE Professor F S Northedge. As a student of International Relations at LSE in the 1970’s, his “!00 Years of International Relations” was one of the set texts we studied.