Nicholas Allen offers an in-depth analysis of Boris Johnson’s new cabinet and places the reshuffle in a historical context. He writes that the new prime minister has made the parliamentary arithmetic even less favourable to his Brexit plans, and explains why the reshuffle indicates that there may be another general election sooner rather than later.

Nicholas Allen offers an in-depth analysis of Boris Johnson’s new cabinet and places the reshuffle in a historical context. He writes that the new prime minister has made the parliamentary arithmetic even less favourable to his Brexit plans, and explains why the reshuffle indicates that there may be another general election sooner rather than later.

Boris Johnson has finally achieved his lifelong ambition by becoming prime minister. The ensuing reshuffle or reconstruction of the Tory government was remarkable. Of the 27 ministers who attended Theresa May’s last cabinet, only 11 would be invited to attend Johnson’s first.

Forming a cabinet is a challenging business. New prime ministers need to reward supporters, appease or punish rivals and give posts to those with appropriate abilities, seniority and, on occasion, policy preferences. They also need to be mindful of their cabinet’s overall gender, race, regional and factional balance. And the overwhelming majority of their appointments must be drawn from a relatively small talent pool: their party’s MPs. The challenges facing ‘take-over’ prime ministers are even greater. Unlike their counterparts who first take office after winning a general election, take-over prime ministers have had no time to develop their team in opposition. Their government must be an iteration of their predecessor’s choices.

Johnson’s response on taking office was to conduct a wholesale purge of his predecessor’s appointees. Newspapers portrayed the clearout as ‘carnage’ and a ‘massacre’. In practice, not every departure was a clear-cut dismissal or, in a few cases, resignation. The extent to which ministers leave office involuntarily or voluntarily is a matter of degree. Some ministers choose to go knowing a prime minister is about to sack them, others leave after being offered a lesser post in an almost calculated snub.

For example, both David Liddington, sometimes referred to as Theresa May’s de facto deputy, and Chris Grayling, her transport secretary, in all likelihood chose to resign in anticipation of being dismissed. Jeremy Hunt, May’s foreign secretary and Johnson’s erstwhile rival for the Tory leadership, chose to leave rather than accept a demotion.

Only three members of May’s cabinet publicly announced in advance their refusal to serve under Johnson: her chancellor of the exchequer, Philip Hammond, her justice secretary, David Gauke, and her international development secretary, Rory Stewart. They may well have expected the sack but they also took clear positions against the new prime minister and his willingness to countenance a no-deal Brexit.

Johnson’s reconstruction in historical perspective

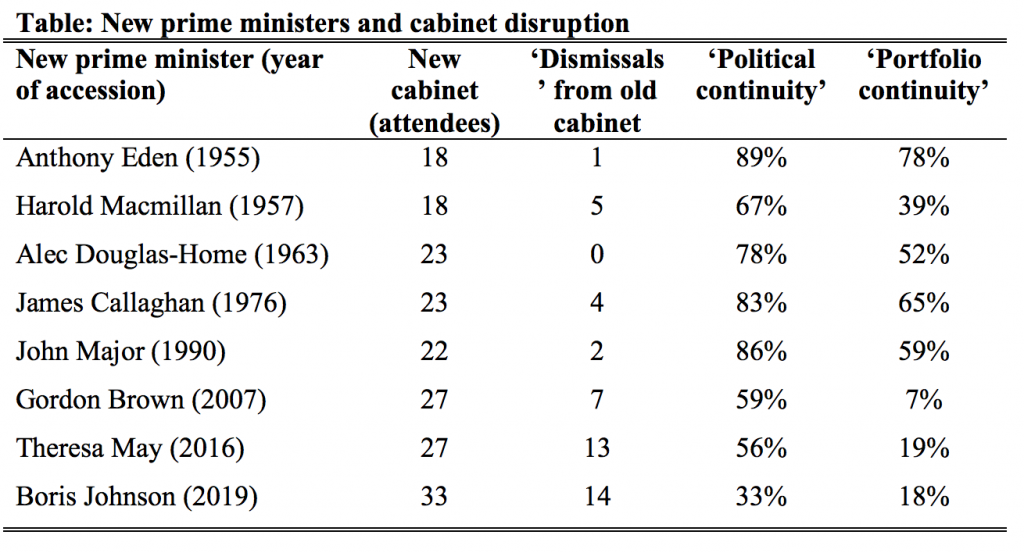

If we exclude these three individuals, Johnson’s cabinet reconstruction involved the dismissal of no fewer than 14 ministers (including pre-emptive and forced resignations). As the table below illustrates, he stands out as the most brutal of the eight post-war take-over prime ministers. Only Theresa May comes close: she dismissed 13 members of David Cameron’s cabinet when she took office. The next bloodiest purge was Gordon Brown’s in 2007, when he sacked seven of Blair’s cabinet ministers.

The table also reports two other measures of disruption: the new cabinet’s ‘political continuity’—the proportion of members who sat in the outgoing cabinet—and its ‘portfolio continuity’—the proportion of members in the new cabinet who held the same job in the old cabinet. These measures confirm just how extensive Johnson’s reconstruction was. The ‘political continuity’ between May’s and Johnson’s cabinet was comfortably the lowest of the eight prime ministers. Just one-third of ministers attending his cabinet attended May’s. In contrast, all other incoming prime ministers since 1945 retained at least half of the old cabinet in one job or another.

The low continuation in Johnson’s case is partly the result of Johnson’s butchery, and partly the result of his decision to increase the number of ministers attending cabinet. Whereas 18 ministers formally attended Anthony Eden’s new cabinet, no fewer than 33 attended Johnson’s. Britain’s supreme collective decision-making body has almost doubled in size since 1955.

Only in respect of ‘portfolio continuity’ was Johnson’s reconstruction not the most disruptive. Instead it was the second-most disruptive after Brown’s in 2007. Six ministers attending May’s cabinet retained their posts under Johnson, including the Brexit secretary, Stephen Barclay, the work and pensions secretary, Amber Rudd (although she also gained the women and equalities remit), the leader of the Lords, Baroness Evans, the health and social care secretary, Matthew Hancock, the Welsh secretary, Alun Cairns, and the attorney general, Geoffrey Cox.

What to make of the new cabinet?

What was the purpose such an extensive purge of Theresa May’s ministers? The first and most obvious answer is that it was clearly meant to signal a break with her government and failed Brexit strategy. It was also a very brutal assertion of prime ministerial power. Ministers who are not with him—personally or ideologically—can now consider themselves dispensable.

A second and related answer is that Johnson now has a cabinet that is in accord with his commitment to risk a no-deal Brexit if he cannot renegotiate the Withdrawal Agreement with the European Union. He has created space around the cabinet table to bring in, or back, a number of committed no-dealers, including Priti Patel, the new home secretary, and Theresa Villiers, the new environment secretary, who took a prominent role in the 2016 Leave campaign.

From Johnson’s point of view, the new cabinet establishes his credentials with the EU as a prime minister who is serious about leaving without a deal. It also lessens the threat from the Tory hard-Eurosceptic right. Jacob Rees-Mogg, former chair of the European Research Group, can no longer snipe from the sidelines. He is the new leader of the Commons.

Johnson’s approach also reduces the prospects of any cabinet resignations down the line if there is a no deal. Jo Johnson, the new universities minister, who quit May’s government in 2018 because he opposed Brexit and wanted another referendum, has presumably reconciled himself with his brother’s worldview. Blood, it seems, is thicker than principle.

Second chances and chancing an election

There are three additional points worth making about Johnson’s new cabinet. The first concerns the number of what might be called cabinet retreads: ministers who have previously attended cabinet. If Andrew Bonar Law appointed the ‘second-eleven’ government in 1922—so-called because several of the most prominent Tories refused to serve—Johnson has appointed a second-chance government.

In addition to the prime minister, who resigned as foreign secretary in July 2018 in opposition to the Chequers agreement, and his brother, the new cabinet contains three other ministers who quit in protest at May’s Brexit strategy: Dominic Raab, Andrea Leadsom, and Esther McVey. It also sees the return of Nicky Morgan and Theresa Villiers, who were sacked in 2016 by Theresa May.

More controversially, the new cabinet contains three retreads whose careers were previously interrupted by scandal: Patel, who was sacked as international development secretary in 2017 for breaching the ministerial code; Gavin Williamson, who was sacked as defence secretary following a leak from the National Security Council earlier this year; and Grant Shapps, who resigned from Cameron’s government in 2015 over allegations about bullying in the Tory party.

Readmitting to the fold ministers tainted by scandal can be a potentially risky business. On the one hand, a lack of political judgement—an enduring defect in a minister—may have been a factor in their initial departure. On the other hand, the media may well subject these individuals to even greater scrutiny, potentially increasing their chances of being caught out over even the most minor transgression.

The second point about the new cabinet concerns its orientation to Brexit. Reaching out to Tories opposed to a no-deal is seemingly not Johnson’s priority. Instead, he has used his powers to create a government that is fully committed to leaving the EU by 31 October. It is entirely consistent with a strategy to appeal to supporters of Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party.

The third point is the parliamentary challenges created by the reconstruction. May took office as the head of a divided party with a wafer-thin parliamentary majority. Johnson takes office as the head of an even more divided party with no parliamentary majority.

Johnson has now sent a number of senior politicians to the backbenches, some of whom, like Hammond, have already promised to oppose a no-deal Brexit, others who may now hold a grudge. The new prime minister has made the parliamentary arithmetic even less favourable to his long-term plans. Just as he wants to win back support from the Brexit Party, his reshuffle seems to have been based on an assumption that there may be a general election rather sooner than later.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. The post appeared first on LSE British Politics and Policy. Featured image credit: Chatham House under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

Nicholas Allen is Reader in Politics at Royal Holloway, University of London.

It is not surprising that Boris Johnson is faced with a challenge, because the Tory Party was split – so he needed ‘Brexit’ and ‘Johnson’ parliamentary supporters. He achieved the election for leadership (who else was there) of the Conservative party and he progresses with his often ill thought out (self obsessed) agenda.

What he, and many pundits, do not appreciate, is that the UK electorate, as a whole, will not accept a ‘No Deal Brexit’.

If that is threatened the clamour for another referendum would rise.