Although the Tories gained back votes from UKIP in 2017, their hard Brexit rhetoric also lost them votes to Labour. But if the party softens on Brexit to gain those back, they could once again bleed voters to a resurgent UKIP. Heinz Brandenburg and Anders Widfeldt explain the data behind this dilemma.

Although the Tories gained back votes from UKIP in 2017, their hard Brexit rhetoric also lost them votes to Labour. But if the party softens on Brexit to gain those back, they could once again bleed voters to a resurgent UKIP. Heinz Brandenburg and Anders Widfeldt explain the data behind this dilemma.

If everything had gone to plan, the main story of the 2017 General Election would have been how the Conservatives increased their majority in the House of Commons by taking votes from UKIP. But the voters had other ideas, and we are now faced with the second hung parliament of the decade.

UKIP did of course lose lots of votes, and are at the moment leaderless. Still, there are two key questions about the party, which have been somewhat drowned by other political developments. One is where the UKIP votes went, now that the Tories saw their majority reduced. The other is what the future holds for UKIP, after losing more than 8 in 10 votes compared to 2015.

© Copyright Oast House Archive and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

In and of itself the core Conservative election strategy – to target UKIP voters with their hard Brexit rhetoric – was a resounding success. Ashcroft polls conducted around polling day suggest that 57% of former UKIP voters switched to the Tories. In addition, we ran a simple regression analysis relating UKIP losses to the change in Conservative vote share across all English and Welsh constituencies (in constituencies where UKIP did not stand in 2017, the loss was measured as their 2015 share of the vote in the same constituency). We found that for every percentage point that UKIP lost in a constituency, the Conservatives gained 0.95 of a percentage point, i.e. almost all.

The problem was that the Tories also lost votes to other parties, mostly Labour. On average over 6% of Tory voters in each constituency went elsewhere. We estimate that for every two voters they gained from UKIP, the Conservatives lost one of their own to Labour. So, if the attempt to woo UKIP voters was successful, it looks like it had unintended side-effects.

The fact that so many UKIP voters did go to the Tories was not as such unexpected, with the governing party’s emphasis on a “hard Brexit” before and during the campaign. But the shift from UKIP to the Tories was not merely driven by short-term factors, as supported by research we conducted about UKIP’s support base 2010-2015.

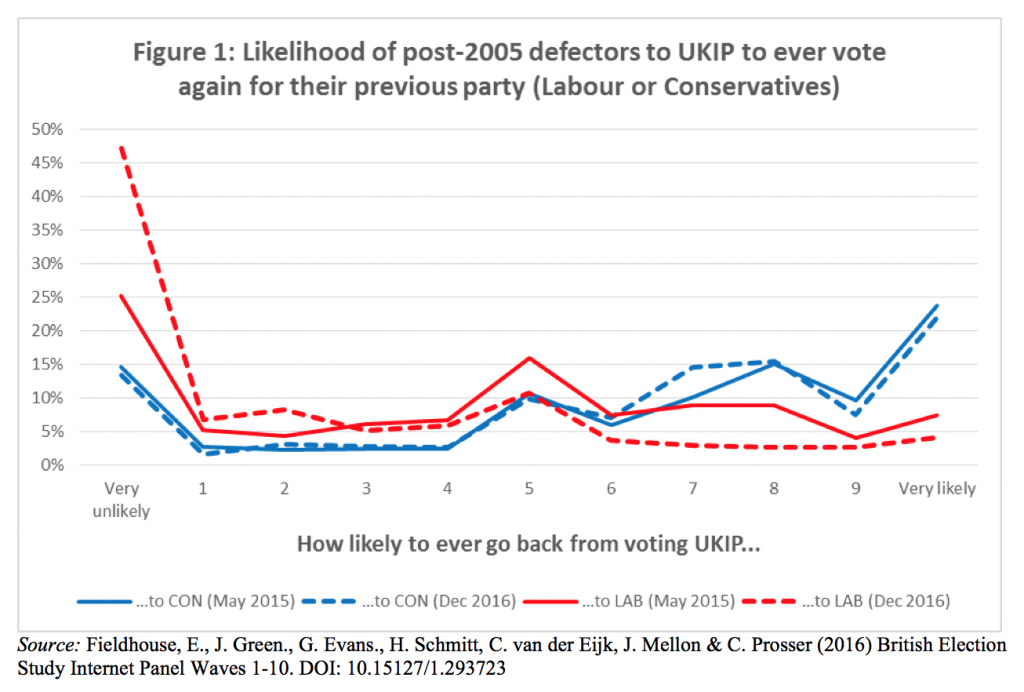

Analysing respondents’ feelings towards the British parties, we found that UKIP’s main competitors for sympathies and votes were the Conservatives. The BNP was also a viable alternative for many UKIP supporters, while Labour was hardly in the picture. The latter may be surprising given that roughly 1 in 5 newly recruited UKIP voters had defected from Labour, before or after 2010. But for most Labour defectors, a return to Labour had become inconceivable, as illustrated in Figure 1:

Figure 1 reports how likely defectors from Tories and Labour to UKIP think it is that they would ever vote for their old party again. (These are so-called Propensity to Vote. The survey question is “How likely is it that you would ever vote for each of the following parties?”. Asking this question about their former party to respondents who had moved from Labour or Conservatives to UKIP, we get a measure of the likelihood of a return to the erstwhile favourite party.)

The data are taken from the British Election Study Internet Panel study. We only selected those who voted either Labour or Conservative in 2005, but UKIP in 2015. The solid lines report their answers just after the 2015 election, in which they voted UKIP; the dashed lines are from December 2016, i.e. when the intentions of the Conservative government to favour a hard Brexit had become apparent.

Figure 1 shows that ex-Tory voters could easily imagine themselves moving back, while Labour defectors to UKIP have closed the door on their former party. The trend grows stronger the further away we move from the 2015 election. While three-quarters of Labour defectors consider it unlikely to ever move back (scoring <5 on the 10-point scale), almost 50% exclude the possibility altogether (scoring 0). Meanwhile, three-quarters of Tory defectors think it more likely than not to move back (scoring >5). Most notably, these Tory defectors consistently saw a return as a distinct possibility – there is virtually no difference between the two blue lines. Theirs was not a change in party allegiance, but more of a strategic vote.

The future of UKIP is thus very much in the balance. The party’s raison d’être has hardly disappeared. The Brexit process is in progress, but is not certain to reach a conclusion approved by UKIP supporters. If they regard the eventual Brexit as too soft, those who now moved back from UKIP to the Conservatives could just as quickly return. The softer the Brexit, the more likely a UKIP resurgence.

But that is not the only possible scenario. UKIP’s support base also includes many who have moved from BNP (or from Labour via non-voting and/or BNP). The party thus has two main choices. One is to aim for the position as a mainstream guardian of Brexit, reclaiming mainly Tory voters unhappy with the route Brexit may take. The alternative is to consolidate the smaller base of more radical supporters, some of whom have in the past supported BNP.

For the Tories, there may be problems ahead. Gaining votes from UKIP did not help secure an outright majority because it meant losing votes to Labour. These voters may not easily come back, at least not as long as the Tories stick to the hard Brexit agenda. If, on the other hand, the government party softens on Brexit, they could bleed voters again to UKIP.

This article first appeared on EUROPP and it gives the views of the author, and not the position of LSE Brexit, nor of the London School of Economics.

Heinz Brandenburg is Senior Lecturer in Politics at the University of Strathclyde.

Anders Widfeldt is Lecturer in Nordic Politics at the University of Aberdeen.

You say ‘many’ UKIP voters came from the BNP.

When did the BNP ever get anything like the millions of votes UKIP got recently?

Surely the maths means that well less than half of UKIP voters could possibly have come from the BNP?