Only a quarter of Britons with a university degree voted Leave, which has led many to conclude that education makes people less Eurosceptic. Sander Kunst (University of Amsterdam) tested this theory and found that the association is not simple.

Only a quarter of Britons with a university degree voted Leave, which has led many to conclude that education makes people less Eurosceptic. Sander Kunst (University of Amsterdam) tested this theory and found that the association is not simple.

A small majority of 51.9% voted to Leave the EU. Recent studies show that education level was one of the most important determinants for voting Leave or Remain. The work of Sara Hobolt clearly illustrates this point. She shows that around 70% of Britons without any qualifications voted Leave, while only 25% of voters with a university degree did. This divide led the Independent to speculate that Brexit could have been prevented if only Britons received slightly more education.

It is an interesting proposition: could Brexit have been prevented if the population had spent a few more years in school? More generally, is there a causal relationship between education and Euroscepticism? In a recently published article in European Union Politics, Theresa Kuhn, Herman van de Werfhorst and I have examined this specific question.

From association…

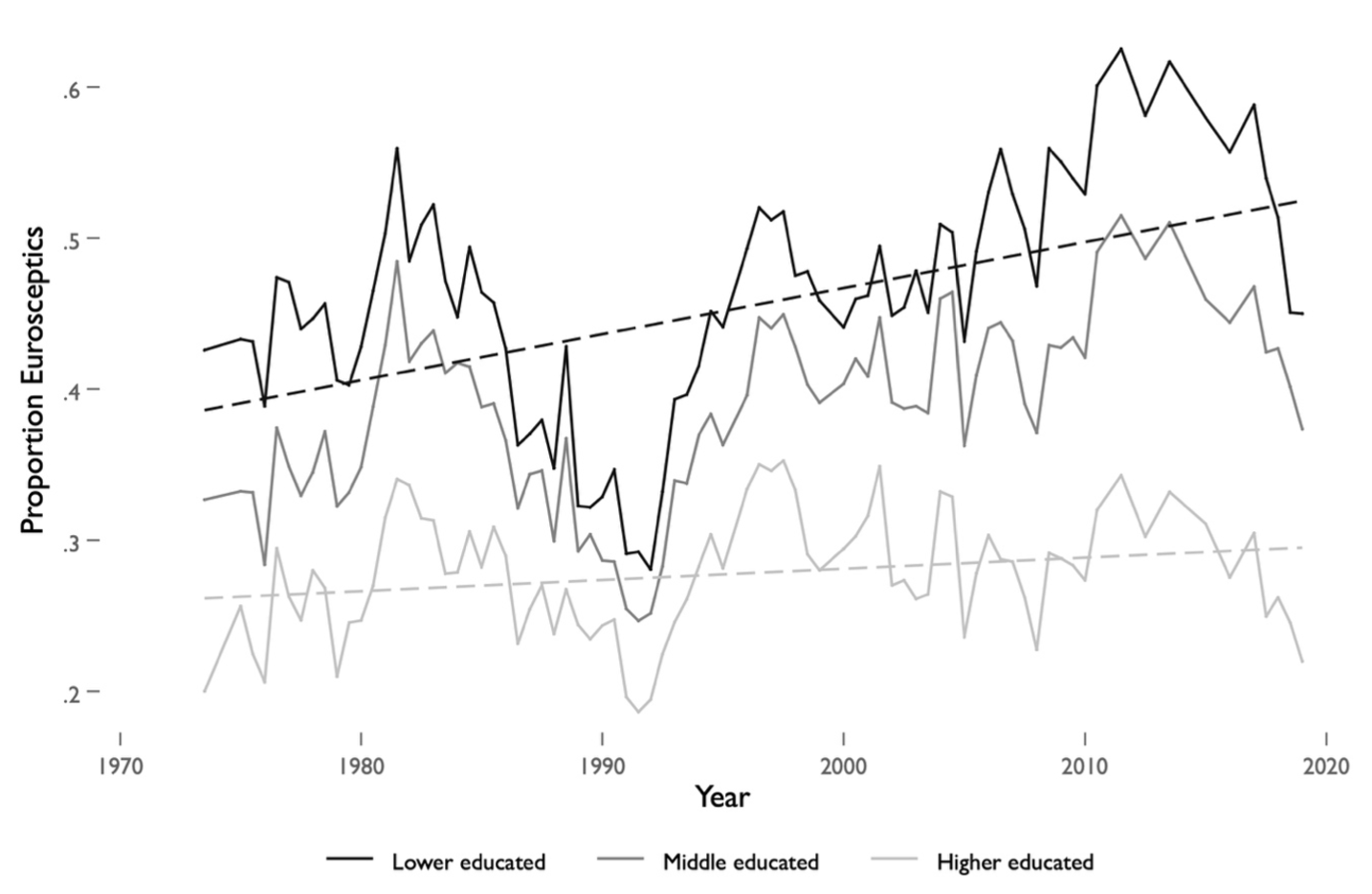

The clear relationship between education and Euroscepticism is not only visible in the UK. Those with more years of education report more enthusiasm for the EU in almost every western European country (see figure 1). Although these differences have been present since the 1970s, the gap between different levels of education in Euroscepticism has been significantly exacerbated over time.

Figure 1: Euroscepticism in western Europe between 1973 and 2018

Source: Eurobarometer

A number of explanations have been put forward to explain this divide. The higher educated are more supportive of the EU as they profit more than the less educated from further European integration, due to their knowledge and skills. Because of the disappearance of hard borders within Europe, studying or working in another EU member state is a realistic possibility for many. However, this possibility seems to be especially available for those with higher educational credentials. For example, a cashier at Tesco in Birmingham is less likely to move to Austria to get another job than a computer programmer who can market her or his skills anywhere in Europe. As the ‘winners’ of globalisation, they are not limited by national borders and can enjoy all the benefits that European integration offers. And as a result, they are more positive about the EU.

Education is also thought to socialise students into a set of (cosmopolitan) values, such as diversity, pluralism and individual freedom. As a result, a higher level of education is associated with holding fewer nationalist sentiments and feelings of being culturally threatened. This in turn may boost support for cosmopolitan political projects such as the EU.

…to causal relationship?

The implicit assumption of these explanations is that the relationship is causal: spending more years at school and university leads to a more positive opinion about the EU.

But is this the case? The mechanisms described above are primarily examined using research designs that can only test for association, not causality. Moreover, recent studies show that a variety of background variables is associated both with educational attainment and political attitudes (here, here and here). Many of these factors (e.g. political socialisation at home, cognitive skills etc.) are hard to quantify and/or to take up in commonly used statistical models. By omitting these variables it is likely that previous work has overestimated the effect of education on Euroscepticism.

The ‘gold standard’ to test for causal relationships is to conduct an experiment. In the perfect scenario, we would recruit a group of students, flip a coin to determine who will quit school and who will continue studying, and afterwards see if there is a significant difference in Euroscepticism between the two groups. Of course, this is a pipe dream, since no ethical board would ever approve this plan…

Natural experiment

To approximate the causal relationship between years of schooling and Euroscepticism we therefore use a quasi-experimental method, namely a regression discontinuity design. We focus on five changes in the education systems of Great Britain (1947, 1972), the Netherlands (1974), Denmark (1958) and Sweden (1965), which as a result changed the compulsory schooling age. In our study we compare the cohorts that were just below and just on or above the threshold to be exposed to the reforms. Whether a child was exposed to the reform or not is in the end dependent on chance. Accidentally being born a year later or earlier can mean a year (or more) of additional schooling, while many other important background variables will be identical.

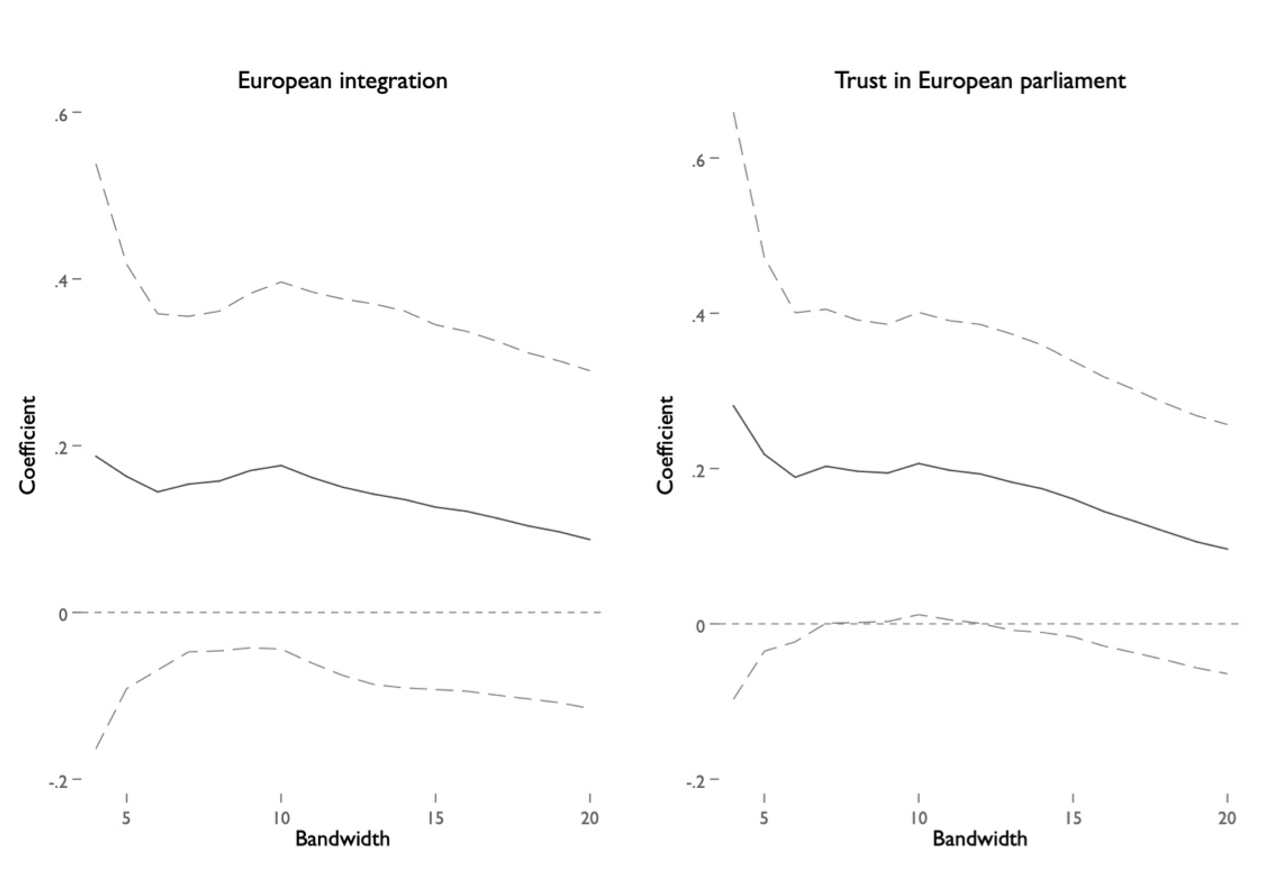

The results of our study indicate that cohorts that were just below and just on or above the threshold to be exposed to the reforms differ significantly in their years of schooling (see figure 2). However, when we look at attitudes towards the EU (support for further European integration and trust in the European Parliament) we do see differences, but these differences are not statistically significant (see figure 3). Put differently, the additional schooling did not significantly impact their attitudes towards the EU. In contrast to the robust association found in the political science literature, we do not find conclusive evidence for a causal relationship between education and Euroscepticism.

Figure 2: Average years of schooling for each birth cohort (with 95% confidence interval)

Figure 3: Effect of schooling on Euroscepticism (with 95% confidence interval).

What does this all mean?

It is important to note that this does not mean that education cannot have an effect on Euroscepticism. In our study we only look at changes for the period people are in high school and analyse relatively older generations. The research design we used is very useful for uncovering causal effects, but this comes with a price: our results are hard to generalise to other contexts. For example, should we examine the consequences of university attendance, instead of high school? Could there possibly be an effect of schooling for younger generations who grow up in a world where the EU is self-evident? More research is necessary to determine if, and how, education influences the formation of political attitudes. So could Brexit have been prevented with more education? Maybe…

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor LSE.

Sander Kunst is a PhD candidate in the Sociology and the Political Science departments of the University of Amsterdam. His PhD project seeks to investigate the mechanisms underlying the educational divide in cosmopolitan attitudes in Western societies in the age of globalisation.

in a nutshell without the chuff posted, those in the academic bubble, lliving in the leafy suburbs and thus unaffected by the negative affects of the EU- (immigration, pay compression, jobs, public services not private) voted for the rose tinted EU projection- those most affected by the EU policies, who it affects the most on a daily basis- voted to leave.

The answer is obviously ‘No’.

And not just because;

– Nobody cast their vote in 2016.

– No opinion-poll, glorified or otherwise, yields ‘a’ result.

– There was never a majority of those canvassed that expressed an opinion ‘to’ leave the EU.

Not having a degree-level education myself; I feel free to stick my neck out even further:

– There never was a referendum on the public utility of EU membership, even in 2016.

What the public was forcibly embroiled in was a ‘Party-Political attitude to EU membership’ survey.

This was clear from the outset, and reinforced by all in Party-Politics replacing the living and breathing, electorate with the abstract: Will of the people.

– I’m off now to return to mangling my wurzels.

What condescending middle class posh tosh, if you voted to leave you must be uneducated. I voted to leave, I am educated to PH.D level. I voted to leave as I did in ’75 because the EU is an organization that is clearly fascistic in its presentation and functions. MEPS do not generate legislation, that s for the unelected Commission, the same commission determines how money (grants etc.) is disbursed, upset them and you will be punished. If the commission bring out a law and it is passed by the supine EU parliament there is nothing the local voter can do about it. A case in point is vehicle insurance, this, in the UK, was always based on perceived risk so women had lower rates than men. Along comes the commissions and decides that in the name of equality there should be no discrimination on the basis of gender, the risk element should be ignored. Logical eh? To add insult to injury the commissions then decides that the uninsured should be able to claim in the event of an accident against the insured driver. Being a law breaker is therefore encouraged by the Commission. Wedgewood-Benn warned us in 1975 that this EU super state would come about, not enough of us listened to him and here we are poor supplicants at the knee of the Commission, all highly educated dreamers who are a long way away from the normal population, like the majority of UK politicians who, by definition are undemocratic, Quentin Hogg once described the Hose of Commons as an elective dictatorship, how right he was. This country is not truly democratic. I have no wish to be a part of a super state where I have no effective democratic control over the lawmakers, that is not democracy but tyranny. I have looked beyond the money unlike many of my colleagues.

This is the Britain-centered view that (over-)emphasizes the democratic shortcomings of the EU without acknowledging the EU’s contributions for peace and economic development.

Interestingly, the Brexit mess has shown that the British democratic system is not free from shortcomings either, and the British political elite in my view does not seem to care more about ‘ordinary’ people than any where else in Western Europe.

Personally, as a citizen of an EU country outside Britain, I think I can tell the difference between living in a totalitarian country vs. living in the EU, and I definetly prefer the latter.

This was an interesting read. It was refreshing to see an experimental approach as opposed to another analysis of association. However, as you mention, your results should be taken with a pinch of salt. I question whether an extra year or so of high school is likely to have a sizeable effect on attitudes toward the EU. Rather it is the three (or more) years of attending university that many have found to make the significant difference. Or at least several years of high school. Or maybe the link between education and Euroscepticism applies to the UK only. It would be nice to see further research on this topic.

@Teejay: “As a statistician, I do not have a clue what Figure 3 indicates since the axis label ‘bandwidth’ is not explained.” Yeah, that puzzles me too. Perhaps one has to check the original article, which I don’t right now have time to do 🙂

“The article fails to address the issue that, due to social evolution, younger people have generally spent longer in education than older people and that people’s views can change with age. ” I suppose the argument is that by choosing cohorts just before and just after the change in years of schooling, any influence due to age is minimal. Of course you can’t prove that. As I’m sure you as a statistician are aware, finding perfect Instrument variables is hard, and usually impossible.

I think, nonetheless, the study is highly interesting, even if inconclusive.

As a statistician, I do not have a clue what Figure 3 indicates since the axis label ‘bandwidth’ is not explained.

The article fails to address the issue that, due to social evolution, younger people have generally spent longer in education than older people and that people’s views can change with age. There is a tendency for older people to be more conservative. Also older people have had more experience. It may have come as a complete surprise to younger voters that the Leave outcome did not result in the predicted substantial rise in unemployment in the short term. It would have been less of a surprise to older people who had lived through the ERM debacle and who had observed that the predicted negative consequences of remaining outside the Euro did not happen. The phrase ‘University of Life’ may be a cliché but it does contain some kernel of truth.

The paper states that ‘We focus on five changes in the education systems of Great Britain (1947, 1972), the Netherlands (1974), Denmark (1958) and Sweden (1965), which as a result changed the compulsory schooling age. In our study we compare the cohorts that were just below and just on or above the threshold to be exposed to the reforms’. There is a simple analysis that can be performed here. We can observe in each of the five cases whether or not the group experiencing the longer education were more EU sympathetic or not (however marginal). If the relationship between education duration and EU sympathy was purely random then we would have roughly a 3% chance of observing in all 5 cases that the longer educated group was more EU sympathetic (0.5^5). What did the data actually show?

I’m educated to degree level, plus some post graduate courses and have lived in 5 different countries. I voted to leave because I know what the EU is all about and fully understand it’s evil intent. The younger ‘educated’ generation are the ones that have been indoctrinated by Lefty & Liberal propaganda at school and university for many years. Surprise, surprise – they voted to remain. As for the ‘uneducated’ they are much more savvy than you assume. They see life as it is – NOT through EU rose-tinted spectacles. Many of them are fully aware of UN Plan for 2030, the Barcelona Declaration, the Lisbon Treaty and the UN Migration Pact. Then, of course, the C-K Plan. With such knowledge why on earth would they wish to stay in the EU? If more of the electorate really knew about the EU, the vote would have been 70+% OUT and our odious parliament would not have dared to overturn the Referendum.

This comment refers to the C-K Plan, which somewhat confused me, as I am sure it does other people.

Searching on Google, I came across the famous inter-war pan-European idealist Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi, and I presume the “C-K Plan” is supposed to refer to him?

A world of universal respect for human rights and human dignity, gosh how terrible @GeoffG

UN Agenda 2030

The Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development was launched by a UN Summit in New York on 25-27 September 2015 and is aimed at ending poverty in all its forms. The UN 2030 Agenda envisages “a world of universal respect for human rights and human dignity, the rule of law, justice, equality and non-discrimination”. It is grounded in the Universal Declaration on Human Rights and international human rights treaties and emphasises the responsibilities of all states to respect, protect and promote human rights. There is a strong emphasis on the empowerment of women and of vulnerable groups such as children, young people, persons with disabilities, older persons, refugees, internally displaced persons and migrants.

The Agenda’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), and their 169 targets, aim at eradicating poverty in all forms and “seek to realize the human rights of all and achieve gender equality”.

You don’t really believe in that BS do you? It’s world communism carefully wrapped in a palatable form for all the little unthinking cabbages to applaud. Get ready for an ever decreasing standard of living whilst the strength and hard-earned wealth of all Western countries is given away to the backward, feckless and useless It’s work in progress as we speak and only fools cannot see it. All it will do is cause a massive increase in the world’s population, which even now is unsustainable. Be careful what you wish for.

When the hypothesis of negative correlation between education and leave is applied to Northern Ireland we see other variables at work, loyalism or nationalism, religion. ethnicity which could override that of education.