After the conclusion of negotiations between the twenty-seven EU Member States and Boris Johnson’s government on the UK’s EU withdrawal agreement, Brexiteers seem to finally be on the verge of achieving their goal, writes Thierry Chopin (ESPOL/Bruges). But will Brexit succeed? Probably not, or else in its current form it will cause many losers, including those who voted to leave the EU and could turn bitter.

In 2016, a majority of eligible voters, in particular in England, decided that their country should leave the European Union. The deal that was patiently negotiated by Theresa May and the twenty-seven Heads of State and government of the other EU Member States was not ratified by the UK Parliament, which had become more fragmented than ever. None of the motions submitted to a vote (soft Brexit, reconsideration of Brexit, customs union, second referendum) obtained a majority. Prime Minister Boris Johnson now defends – together with his closest advisers (first and foremost Dominic Cummings) – the option of a hard Brexit according to which the UK’s economic model should transition to a ‘Singapore-on-Thames’ to achieve success outside the EU. In such a context, the question if Brexit will succeed is more pertinent than ever[1].

What is the objective of Brexit: Global Britain or isolationism?

During the referendum campaign, two seemingly contradictory political visions could be found amongst ‘Leave’ supporters. The first is isolationism, fuelled by fear of immigration and the quest for sovereignty, reinforced by the influx of refugees. In fact, many Brexit supporters have been confused about freedom of movement in Europe and immigration from beyond the EU’s borders. It should be noted here that some in the UK (particularly those from Commonwealth backgrounds) see Brexit as an opportunity to address the perception that nationals from the rest of the world are treated unfairly in comparison to EU citizens when trying to obtain the right to work and live in the United Kingdom.

The second vision is that the United Kingdom should become an advocate for free trade and an offshore financial centre. Supported by the memory of the empire and the good health of the Commonwealth, as well as the desire to preserve its claimed status as the world’s leading financial centre, it affirms the global vocation of the United Kingdom (Global Britain), which European regulatory constraints supposedly hinder. The two visions, isolationism and globalism, are based on political and identity-based logic rather than economic and utilitarian rationale. And their contradictions are apparent: Leave supporters dream of making the United Kingdom a ‘great Switzerland’, globally open to foreign capital and trade in manufactured goods and services (while protecting its agriculture), connected to the EU through sectoral agreements, but closed to immigration.

But it is far from certain that the majority of British citizens who voted in favour of Brexit want the United Kingdom to turn into ‘Singapore-on-Thames’. While this was true for neoliberal Brexiteers, leftist Brexiteers rather hoped for a return to a purely national welfare state unconstrained by EU competition rules. This was in line with the idea that the Labour party, if it came to power, could more easily implement its programme once it had rid itself of the ‘neoliberal treaties’ on which the EU is based. Moreover, arguments around the economic benefits of openness were mainly invoked by ‘Remainers’. When Leave supporters discussed economic implications, many defended the need to rebalance between London, which took advantage of the country’s membership in the EU, and the many other parts of the country that failed to make the most of European and international economic and financial openness. In this respect, it is striking to see to what extent the issue of inequality has played an important role in the economic discourse surrounding Brexit. Many would like to see the United Kingdom become less open than in the past; British farmers and fishermen seem to want less competition rather than more.

What brought together Brexiteers was the idea of “taking back control”, each component with the hope that its political agenda would eventually triumph domestically. The decision to leave the EU indeed only became possible because a majority of British citizens thought there were national alternatives to EU membership. For Brexiteers, this meant to return full control to the national parliament overall decisions applying to the United Kingdom. Ironically, however, many of them then expressed frustration with the role of the UK Parliament in the Brexit process and supported its prorogation (which was later invalidated by the Supreme Court).

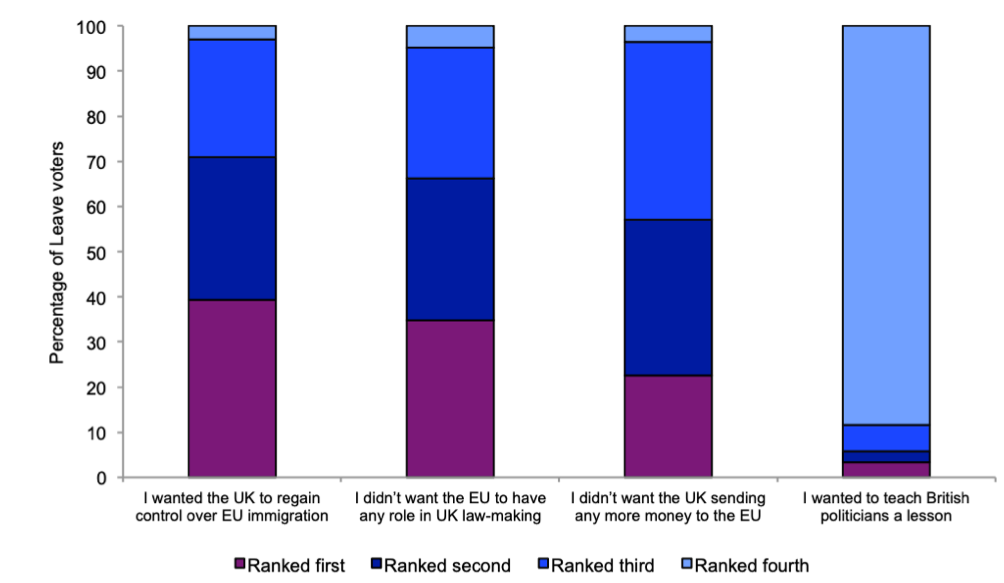

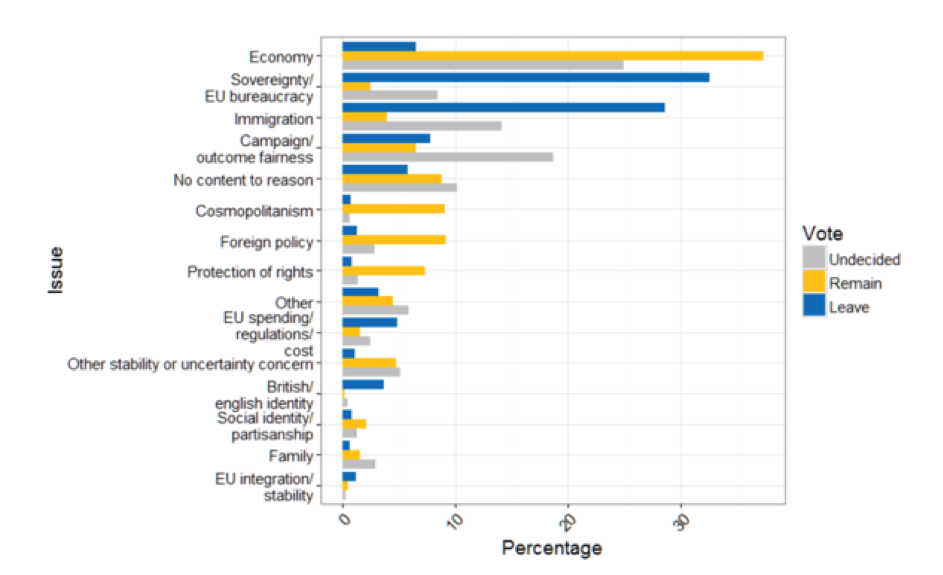

The common narrative among Brexiteers was therefore mainly political, emphasising the themes of sovereignty and immigration (see Figures 1 and 2) and brushing away the different political agendas of its promoters. This contrasted with the clear economic focus of remainers (Figure 2).

Figure 1 ▪ Reasons why Leave voters voted Leave

Source : CSI Brexit 4 : “People’s Stated Reasons for Voting Leave or Remain“, The UK in a Changing Europe, Centre for Social Investigation, Economic and Social Research Council, 24th April 2018

Figure 2 ▪ The themes that influenced the votes by Brexiteers, Remainers and the undecided

Source : Chris Prosser, Jon Mellon, and Jane Green (2016), “What mattered most to you when deciding how to vote in the EU referendum?“, British Election Study, 11/07/2016.

The blindness of hard Brexiteers

Several elements also highlight the weakness of the “Singapore-on-Thames” promise of neoliberal Brexiteers and the risk that the UK may end up with less rather than more economic sovereignty in globalisation.

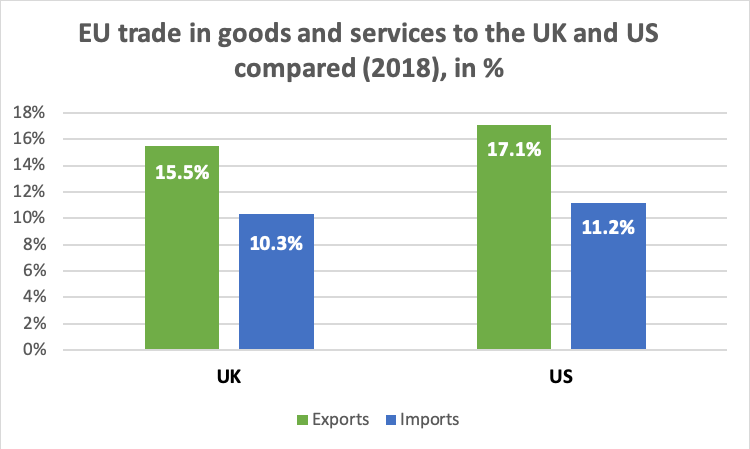

First, will the United Kingdom’s ability to negotiate free trade agreements with third countries be stronger outside the EU than within it? There are good reasons for skepticism. The EU’s economic and commercial weight is much greater than the United Kingdom’s. In addition, the EU is less dependent on the United Kingdom than the other way around: 46 per cent of UK exports of goods and services are exported to the EU (compared to 15.5 per cent of exports from the EU to the UK); 53 per cent of UK imports are from the EU (compared to 10.3 per cent of European imports coming from the UK).

Figure 3 ▪ Comparison of trade in goods and services between the UK and the EU and between the UK and the USA in 2018 in per cent.

Source : ONS, PinkBook

Figure 4 ▪ Comparison of trade in goods and services between the EU and the UK and between the EU and the USA in 2018 in per cent.

Source : European Commission, DG Trade

Negotiations on trade agreements with major powers such as the United States, China and India will be long, and tough for the United Kingdom once it is outside the EU. Negotiating alone puts it in a much less favourable position than negotiating as a Member State of the EU. Given the new power differential that would result from a hard Brexit, it is likely that access to the UK market for US agricultural and agri-food products would have a negative impact on British farmers who would not necessarily benefit from the trade. If some sectors (such as financial services and hedge funds) can benefit from this new situation, it will also result in losers and involve costs for other sectors.

Second, access to a country’s market is provided under a compensation logic which involves third countries. For example, Poland has an interest in opening its market to British companies as long as the United Kingdom allows Polish workers access to its market. China and India will not give more favourable market access to the United Kingdom than to the EU, if London does not relax its visa policy towards Chinese and Indians. Japanese companies are closing sites in the United Kingdom to repatriate them to Japan in order to avoid the uncertainty of Brexit and because of the free trade agreement negotiated by that country with the EU. With regard to taxation, the ‘Singapore-on-Thames’ scenario could also lead London to deploy very aggressive tax competition strategies against its former European partners. But a non-cooperative and combative tax strategy would ignore a number of realities: tax competition is already possible within the EU (as showcased by Ireland and Luxembourg); all Member States are in the process of lowering their corporate tax rates (as is the case in France, for example).

Third, would other EU Member States allow this to happen by turning a blind eye? The European (including British) reaction to the United States on taxing multinational technology companies illustrates that this is not obvious. Last but not least, such a tax strategy would involve financial costs for the financing of the British public sector and therefore political and social cost due to the increase in resulting inequalities. Is this really the choice of a majority of British citizens who voted for Brexit?

Can ‘Singapore-on-Thames’ be a model?

The ‘Singapore-on-Thames’ narrative has to be questioned at the political, economic and social level. Politically, it should be recalled that Singapore is governed by an authoritarian and clan-based regime (around a few families) in which there is no democratic competition. Economically, Singapore is not only a major financial centre and its growth has been over-determined by its geographical location: Singapore has a world-class port with logistics, trading and refining activities. Conversely, ports in the United Kingdom are underdeveloped compared to those in the EU, particularly in Antwerp and especially Rotterdam. The comparison with Singapore therefore has its limits; we are not talking about the same economy. London is not Singapore and the United Kingdom is not just London; if that had been the case, the United Kingdom would have remained within the EU.

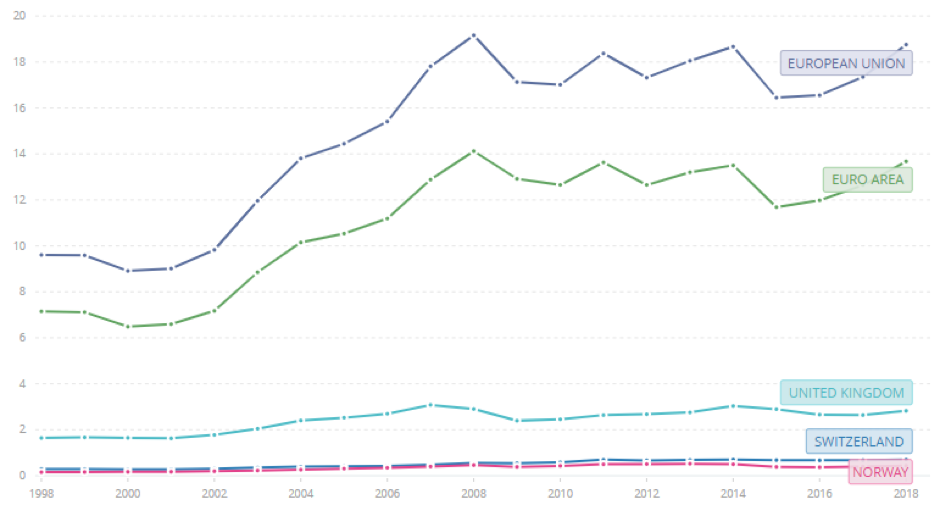

In addition, the comparison with economically prosperous non-EU European countries must be put into perspective. Switzerland, for example, is currently renegotiating its bilateral agreements with the EU, which are not considered satisfactory by either side. Norway is a member of the European Economic Area[2]. It should also be noted that GDP growth in these countries has been lower than that of the United Kingdom (as an EU Member State), the EU, and the euro area over the past 20 years.

Figure 5 ▪ GDP (current US$) – European Union, Euro area, Norway, Switzerland, United Kingdom (in trillion)

Source: World Bank

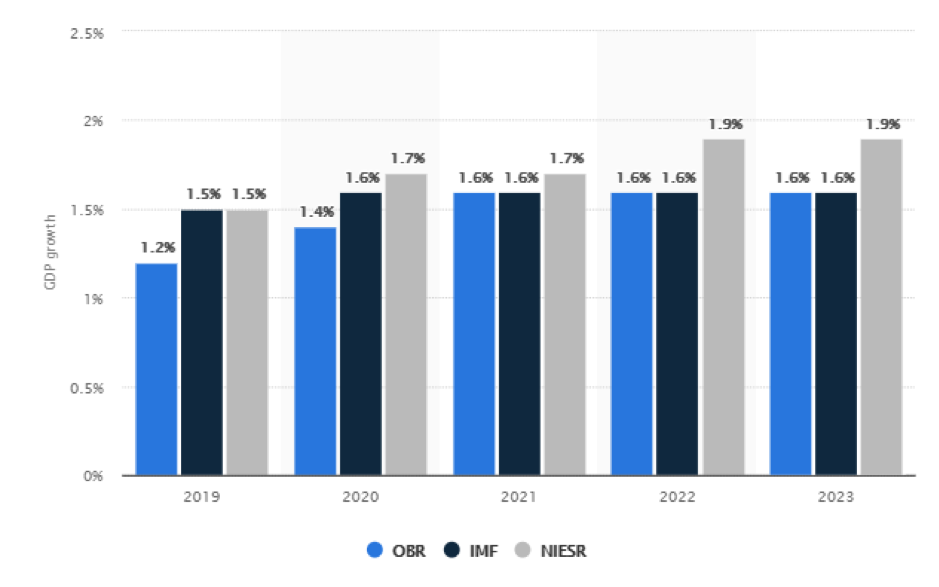

The United Kingdom’s growth forecasts are also falling in anticipation of its exit from the EU.

Figure 6 ▪ Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth forecasts for the United Kingdom (UK) from 2019 to 2023, by institutions.

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility; IMF; NIESR; Oxford Economics

The neoliberal strategy of financial deregulation, led by Margaret Thatcher, has been successful but it occurred within the framework of the EU market that favours financial services. The City is the financial centre for the euro (the second most traded currency in the world) and will remain an important financial centre. But the United Kingdom will lose the financial passport to serve the euro zone from London and the euro zone will condition access to its financial services market on the equivalence of UK and EU regulations in areas where these possibilities are provided for by European legislation.

Finally, the scenario of making London a ‘Singapore-on-Thames’ implies a reduction in taxes, which raises the question of financing public expenditure and in particular the UK’s National Health Service. Although this would not pose any problems for the Conservatives, left-wing Brexiteers may have a different view… The dilemma facing the British is therefore the following: become a poorer and more unequal country but make decisions under apparent sovereignty? This dilemma must be resolved by the British, who, beyond partisan cleavages, will also be divided on the issue between the United Kingdom’s constituent nations, particularly in the case of Scotland.

From the EU’s perspective, vigilance is required. The “Singapore on Thames” agenda may be adopted by a conservative UK government under the pressure of the hard neoliberal Brexiteers within the Conservative party. The emergence of a British competitor on the EU’s doorstep with low taxation, lower standards, lower costs and free ports, would force the EU to protect its market and would end up creating significant economic barriers between the EU and the UK.

***

The Brexiteers could finally succeed. Since the referendum, the likelihood of an exit has never been higher. But will Brexit succeed? Probably not, or else it will cause many losers, including those who voted to leave the EU and could turn bitter. The resulting frustration, resentment and anger will only increase the rise of populism in the form of both nationalist and neo-liberal populism on the one hand and left-wing populism on the other. It is obvious that neither the English, nor the British, nor the Europeans would have anything to gain from such a scenario.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. Image Hans Gerwitz, Some rights reserved.

Thierry Chopin is the author of several books and articles on European integration. He holds a PhD in Political Science from the School for Advanced Studies in Social Sciences (EHESS). He is Professor of Political Science at the Catholic University of Lille (ESPOL, European School of Political and Social Science) and Visiting Professor at the College of Europe (Bruges). He is special advisor at the Jacques Delors Institute.

[1] I would like to thank Jean-François Jamet. Our exchanges and discussions on this subject have been of great value. A an earlier version of this text has been published at the Jacques Delors Institute.

[2] The Agreement on the European Economic Area, signed on 2 May 1992, extended the EU’s internal market to the Member States of the European Free Trade Association, with the exception of Switzerland, which has not ratified the agreement. It therefore includes the EU Member States as well as Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein. While not belonging to the EU, these states benefit from the free movement of goods, persons, services and capital and must apply the relevant European rules without participating in their development or in the decision-making process. They also participate in certain EU programmes (e.g. research, education, environment and cohesion) and contribute to them in proportion to their GDP. However, they do not participate in tax policy, agricultural and fisheries policy or trade policy towards third countries.

A very useful, clear analysis with clear assessments in a language accessible to a wider range of readers than most analyses of this kind, particularly relevant regarding choices faced by the UK electorate.

I agree that this is a very clear analysis of the logical flaws in the Brexiteers’ case. It is also commendable that a prominent French academic has such a clear understanding of the position in the UK.

However we must remember that we are in a “heart over head” situation. The logical results of Brexit have always been very clear to most reasonable people, despite the best efforts of the right-wing press to muddy the waters. There is an emotional attachment to a sense of Britishness as a place apart from continental Europe which remains strong, especially in England outside Greater London.

Good analysis but not true to say that in 2016, a majority of eligible voters, decided that their country should leave the European Union. Actually something like 37% of eligible voters voted to leave. These little details matter.

True, “neither the English, nor the ‘British’ (whoever they are), . . . would have anything to gain from such a scenario. But the Scots, Irish (and Europeans to an extent), will. We will have an independent Scotland and a unified Ireland contributing wholeheartedly to the EU, (or at the very lease to EFTA). Perhaps even Wales will regain it’s freedom. Meanwhile, England can be free to continue its project to return to the 19th century.

This analysis is very consistent with my own thinking for a long time. This is however a very clear analysis based partly on data.

There is one thing missing from your comments on ‘the Singapore-on-Thames’ option. What the leave campaign never mention is that one of the foundations of Singapore’s economy is massive levels of low-wage immigration. The migrant share of the workforce rose from around 3% before independence to around 33% a quarter of a century later. It’s enough to make you ask those pleading a low-regulation low-tax future which Singapore they are referring to.