What is going on with economic expertise? Why is it that it is constantly depicted as simply based on opinion rather than facts, ask Marina Della Giusta, Sylvia Jaworska, Danica Vukadinović-Greetham and Anna De Liddo? In this blog, they present their research which uses network and language analysis to explore the audience and the style of communication of top economists on Twitter.

The Financial Times just published a letter from economists and academics commenting on the likely effects of the spending plans outlined in the Labour Manifesto on the economy, while simultaneously highlighting what the authors’ political leaning was as if this were evidence to qualify the reliability of their assessment. After reading the piece, one simply wonders (yet again) whether this would happen, for example, to doctors. Asked for an expert opinion on the likely effects of spending plans for the NHS on patients, would they too be required to state their political affiliation?

This is of course not new: economics expertise has been presented and perceived as fundamentally biased or at best conflicted for quite a while, most prominently by politicians (Gove’s famous ‘enough of experts’). Precisely those who are expected by the public to use economic expertise to make informed and evidence-based decisions seem to gradually undermine it. The public itself does not really trust economists, something which has worsened since the Brexit referendum or actually understand what economics expertise entails. Findings from the ING survey are indicative: a few understand what economists do (something that several initiatives are aiming to address, most notably the Discover Economics campaign) and only some know that economists are actually involved in the job of policy evaluation affecting all sorts of key areas including social policy, transport, health, crime, education, pensions and try to make sure that the polices are evidenced-based.

So what is going on with economic expertise? Why is it that it is constantly depicted as simply based on opinion rather than facts?

The status of economic knowledge was the subject of a debate a couple of weeks ago at the Bristol Festival of Ideas and although part of the debate was dominated by the “fallacy of forecasting” discussion (much of the distrust in economics is believed to be arising from the failure to predict economic events accurately), several other issues were discussed including the teaching of economics itself in both schools and undergraduate programmes in universities, the need to represent more clearly the fact that most research is indeed very applied and to extremely important questions ranging from climate change to the causes and consequences of inequality. But this is not always clearly communicated to the public partially because economists seem to lack the kind of communication skills that can engage the public and help people make informed decisions.

The supply of economic information

Experts have been increasingly using social media platforms to communicate with their communities and the wider public, prompted by both the need to acquire and disseminate knowledge and to demonstrate impact and public engagement. Whilst scientists have moved on from the understanding of the public as having a cognitive deficit (a deficit top-down model of communication) and developed an engagement model, economists are still in the dark age of a deficit model and show both less engagement with the public or fail to make their expert knowledge relevant to them.

This hampers the public’s understanding of economic knowledge and contributes to the wider current discontent with expert knowledge. Using network and language analysis to explore the audience and the style of communication on Twitter, we compared the top economists and to the top scientists. Although both groups communicate with people outside their respective professions, economists tweet less, mention fewer people and have fewer Twitter conversations with members of the public than scientists. The language analysis of the differences in communicative style finds that in contrast to economists, scientists use a more informal and involved style as exemplified by the frequent use 2nd person pronouns, discourse and politeness markers as well as various forms of evaluative and emotive lexis – features that are almost absent from economists’ tweets. Also, scientists engage the wider audiences through posting interactive and multimedia contents to be watched and listened to, while economists tend to promote traditional written media to be read such as books and research papers that arguably are not accessible to all.

Social media thus offers an opportunity for expertise to re-establish reputation for itself, but only if experts develop a two-way communication style. There is a really nice community of economic experts talking to each other on Twitter (using the #econtwitter), but they very much remain in their own bubble. So much needed engagement with the public is scarce and there is a dearth of economists/expert influencers willing to enter debates in ways that are conducive to public appreciation (which requires not only plain language but also inclusivity in communication) and increased understanding of economic issues.

Image by Steve Jurvetson, Some rights reserved.

The demand for expertise

But do people even care about the economic content of the proposed policies or is it rather the tone that matters both for them to be heard and then to be endorsed?

In 2017 we analysed a large sample of 55 million Tweets collected in the run-up to the Brexit referendum. Focussing on datasets created around popular hashtags reflecting the key issues in the campaign “free movement”, “project fear” “350m” “budget” we found the same content spreading (around 70% of tweets in each dataset are retweets) and there was little diversity in the users represented in “project fear” where a smaller number of users seemed to exert a very strong influence (1/8 of all tweets posted by top 100 users). Trust was a big issue in debates on the cost of the EU membership (350m) and those pertaining to the economic consequences of leaving (“project fear”), providing further evidence for the mistrust of experts and statistics found by post-vote surveys When modelling the networks of tweeters, we found that the most ‘central’ political figures were Boris Johnson, George Osborne and Nigel Farage followed by the most influential media such as BBC and media shows including the Andrew Marr show. These were the actors that seemed to occupy the central position in the digital world of Brexit, exerting most influence on the forming of opinion.

We then focused on the most influential tweets in both camps and explored language and sentiment use. We found that Leave had more influence, that their tweets were, on average, more emotive and substantially more judgemental, towards both individuals, and institutions like the EU. Whenever security and desire were expressed, Remain were far more negative than Leave: “serious economic danger” occurred very frequently in the remain tweets. Leave tweets, instead, constructed secure post-Brexit scenarios (e.g. “a bold, brave new Britain awaits”). Importantly, Remain never celebrated the intrinsic value and security of the EU in the same way that Leave did with its descriptions of the UK out of the EU. Winning the referendum, at least in social media, clearly seemed to require negatively judging opponents, creating a sense of security, and praising the social and human value of what was being defended (not just its economics)!

Will the tone and rhetoric be again important when it comes to the current election? We analysed a set of 1,120 tweets produced between 29 October and now[1]. And yet again, many matters in need of informed economic expertise are discussed such as social care, NHS and Brexit but there is no evidence of them being based on economic expertise. For example, numbers are routinely thrown into the discussion but act more as rhetorical devices of intensification as opposed to being something based on economic facts. Brexit emerged as the key topic in our data set and it is often accompanied by numbers without any justification or economic detail and this is not just due to a lack of space:

No-deal Brexit planning costs us all £billions

@BorisJohnson has announced: A new # Brexit deal An extra £1.8 billion for the NHS

And when the economy is talked about, the most frequent association is strong as in “strong economy” and it only comes from the conservative politicians with no mention of economic experts; here a few indicative examples:

@sajidjavid: Great to see solid Q3 growth – another welcome sign fundamentals of UK economy are strong

@Conservatives: Wages are up and unemployment is down. Our strong economy means we can invest in the country’s priorities.

@MattHancock takes apart Labour’s lies about the NHS. Only @BorisJohnson and a strong economy can fund a brilliant health service.

Wages are up. Unemployment hasn’t been this low since 1975 when I was 9 years old. The strong economy means we can raise the taxes to pay for our brilliant public services.

So ‘economy’ is dropped, when convenient and needed to justify and boost a leader’s or party’s performance or to create credentials for the ‘brilliant’ future to come. Given the dominance of a few powerful voices in steering the debates on Twitter, the question inevitably arises to what extent are opinions expressed on social media representative of the unconditioned feelings of the UK citizens.

But whose opinions do undecided voters actually trust? Do they even trust their own?

We turned to new technologies for public deliberations and analysed public engagement data provided by Democratic Reflection – a new platform for live engagement with political election debates. This new technology enables people to interact with televised political debates in a truly personal and immersive manner, allowing them to express their spontaneous reactions, reflections and feelings towards the ongoing televised debate, in the moment, and before they can be biased by social media dynamics. The audience reactions gathered by the platform can be then analysed and presented to people as personalised analytics, allowing the audience to gain a deeper understanding of both the debate and people’s feeling and opinions towards it. We analysed data coming from a panel of 93 undecided voters using Democratic Replay during the ITV Johnson-Corbyn debate.

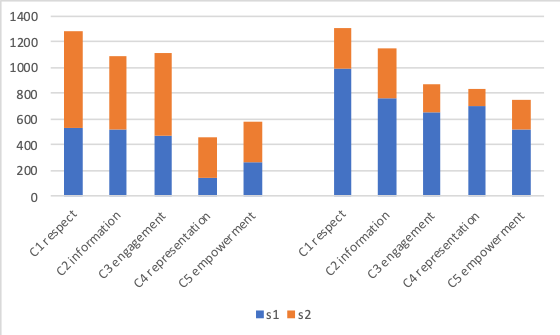

Figure 1

Investigating the live interaction data, which captures how people felt while the speakers where talking, we found that people thought of Jeremy Corbyn as being overall more honest and direct (blue bars on the right stack in Figure 1) and less manipulative then Boris Johnson (orange bars on the left stacks). Jeremy Corbyn was also perceived as providing more interesting information, more engaging and more capable of making a positive difference.

Still, this pro-Corbyn reaction is not confirmed by the perception they had on the overall performance of the debaters when asked at the end of the debate. In fact, only 17 per cent of our participants thought that there was no difference in the speakers’ performance, while 33 per cent of people reported that despite their political stance, they thought that Jeremy Corbyn won the debate, and 50 per cent thought that Boris Johnson did.

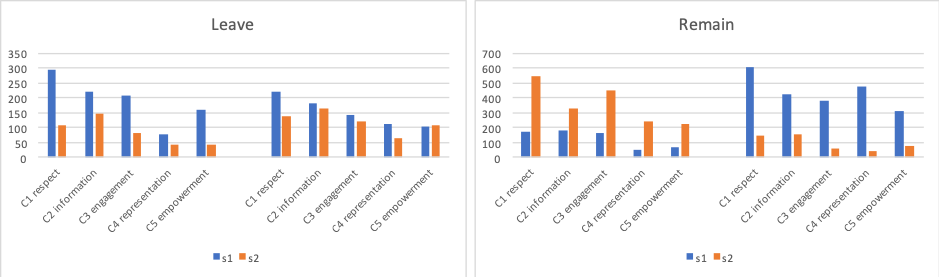

We can deduce from this that there is something either in the performance of the speakers or in participants pre-empted perceptions that affected participants in switching their conscious assessment of the leaders from positive toward Corbyn during the debate, to predominantly positive toward Johnson after the debate. Another explanation for the mismatch could be political pre-positioning. To test this, we considered the stance on Brexit. We classified participants on the base of how they voted for the Brexit referendum (in 4 categories: “remain”, “leave”, “prefer not to say” and “did not vote”).

Figure 2

figures) elicited more positive reactions from remainers, while the positive perception of Johnson (S1 in figures) was coming from leavers. What seems worth noticing is that leavers were more balanced in their assessment of Corbyn. They perceived him sometime positively and sometime negatively, almost evenly, during the debate. On the contrary, remainers were more extreme in their positive perception of Corbyn and rarely reacted positively when Johnson was talking. This finding may be interpreted either as a success, from Corbyn side, in the way he was able to talk to the levers and positively elicit their reactions, but it may be also a worrying sign of silent frustration from the remainers side, which results in them being more extreme in expressing their political reactions.

What do we learn about the role of expertise?

Many alternative, sometimes even competing, interpretations can be inferred from our analysis. Far from being a weakness, this is a value, because it mirrors the complexity of the phenomenon, and the need for expertise to be appropriately examined. On the one hand, this shows how public debate can be effectively supported and analysed by a variety of existing and new social media methods and technologies. On the other hand, it also shows how important is for expertise, both economics and data science expertise, to work hand in hand, to build authentic, evidence-based interpretations of the public debate. Interpretations that are grounded in an in-depth understanding of the complexity of socio-economic and political dynamics can be used to better inform opinions and political decisions, and to reinstate trust in the experts and expertise.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

[1] This is a subset of last 3250 public feed tweets collected on the 12 Nov 2019 from 4 Labour,4 Conservative and 4 LibDem MPs through Twitter API. (The limit is imposed by Twitter)

“What is going on with economic expertise? Why is it that it is constantly depicted as simply based on opinion rather than facts”

It’s not rocket science. It’s very simple. The so-called experts make predictions and get it badly wrong. The most recent example is, of course, last night’s result. The “experts” at LSE did a study that predicted 326 Conservative seats. The result was 364 seats. All other predictions – from the polling organisations, from public opinion, or from bookmakers, were far more accurate than the so-called experts, who are blinded by their own wishful thinking based on their own political bias.