Climate change is now the ever-present reality of human experience. Late last year we witnessed a procession of huge hurricanes batter the US and Caribbean, the largest wildfires on record burn through California, and in Australia, despite the death of up to half of the Great Barrier Reef in back-to-back coral bleaching events, political support for new mega-coal mines and coal-fired power stations. While there is now a clear scientific consensus that the world is on track for global temperature increases of 4 degrees Celsius by century’s end (threatening the very viability of human civilization), our political and economic masters continue to double down on the fossil fuel bet, transforming perhaps the greatest threat to life on this planet into ‘business as usual’.

One response to the failure of government has been a belief that markets and corporate innovation will provide the solution to the climate crisis. As business tycoon Richard Branson has proclaimed ‘our only option to stop climate change is for industry to make money from it.’ Thus while business corporations are major contributors to escalating GHG emissions, they are also often presented as offering innovative ways to decarbonise our economies. But how much faith can we place in corporations to save us from climate change?

In a recently published paper, we explore how major business corporations translate the grand challenge of climate change into strategies, policies and practices over an extended period of time. Our research involved a detailed cross-case analysis of five major corporations operating in Australia over ten years, from 2005 to 2015. During this period, climate change became a central issue in political and economic debate, leading to a range of regulatory, market, and physical risks and opportunities, and each of these five companies were leaders in publicly promoting their engagement with this issue.

However, despite different industry contexts (banking, manufacturing, insurance, media and energy) we found a common pattern over time in which initial statements of climate leadership degenerated into the more mundane concerns of conventional business activity. A key factor in this deterioration of corporate environmental initiatives was on-going criticism from shareholders, the media, governments, and other corporations and managers. This ‘market critique’ continuously revealed the underlying tensions between the demands of radical decarbonisation and more basic business imperatives of profit and shareholder value.

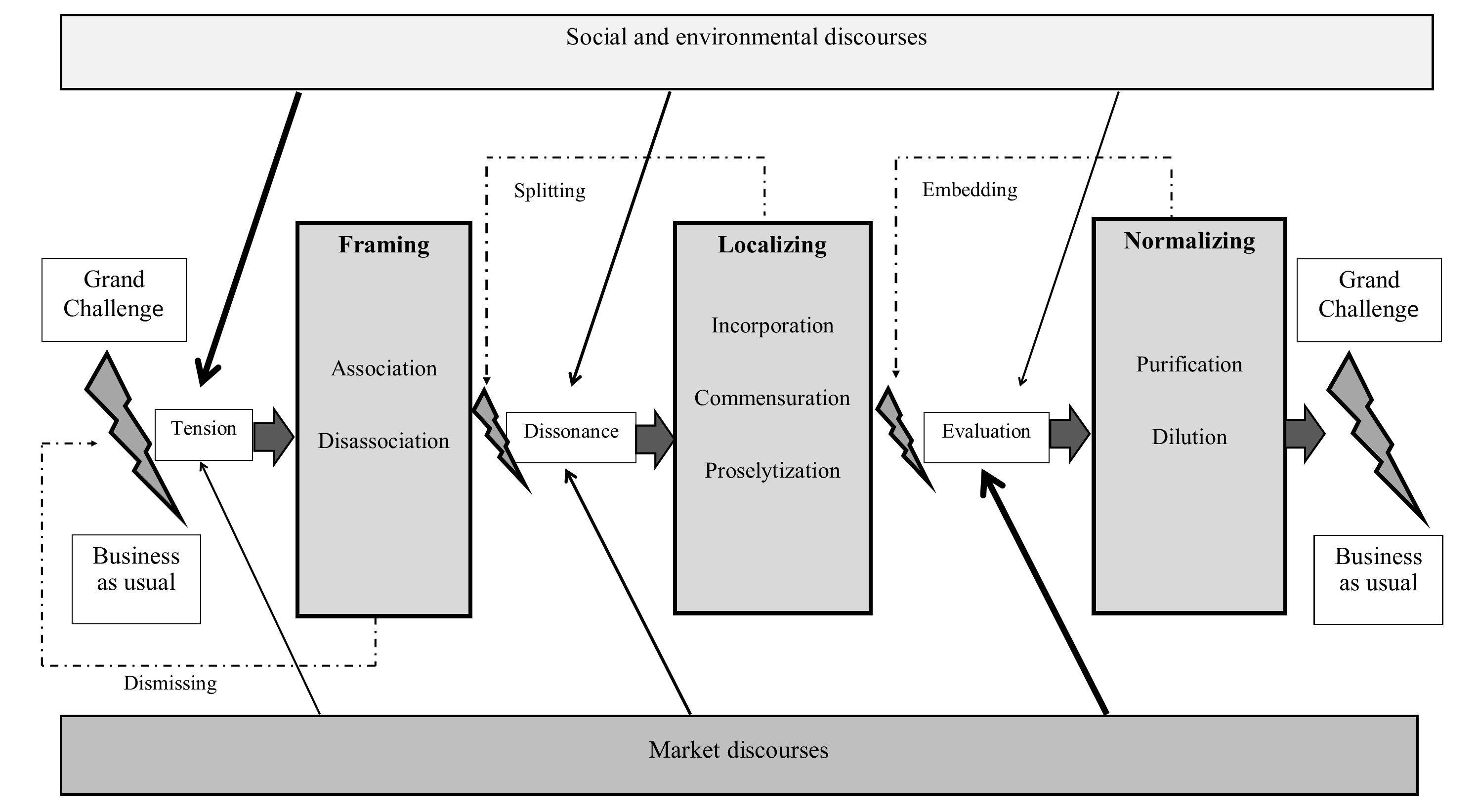

The corporate translation of climate change into business as usual involved three phases. In the first framing phase, senior executives presented climate change as a strategic business issue and set out how their businesses could provide innovation and solutions. Here, managers associated climate change with specific meanings and issues such as ‘innovation’, ‘opportunity’, ‘leadership’ and ‘win-win outcomes’ while ruling out more negative or threatening understandings (e.g. ‘doom and gloom’, ‘regulation’, ‘sacrifice’). In a classic expression of this win-win ethos, the global sustainability manager of one of our case organisations (and one of the world’s largest industrial conglomerates) argued: ‘We’re eliminating the false choice between great economics and the environment. We’re looking for products that will have a positive and powerful impact on the environment and on the economy’.

While these general statements of intent responded to the inherent tension between corporate and environmental interests, convincing stakeholders of the benefits of ‘greening’ initiatives was never assured, and critiques evolved amongst stakeholders and customers who felt their organizations’ environmental efforts either lacked sincerity or failed to satisfy profit motives.

In a second localizing phase, managers sought to make these initial framings directly relevant by implementing practices of improved eco-efficiency, ‘green’ products and services, and promoting the need for climate action. Internal measures of corporate worth were developed to demonstrate the ‘business case’ of climate responses (e.g. savings from reduced energy consumption, measures of increased employee satisfaction and engagement, sales figures from new ‘green’ products and services, and carbon pricing mechanisms). Companies also sought to communicate the benefits of these initiatives both to employees through corporate culture change initiatives, as well as external stakeholders such as customers, clients, NGOs and political parties.

However, over time these practices attracted renewed criticism from other managers, shareholders, the media, and politicians and in a third normalizing stage, climate change initiatives were wound back and market concerns prioritized. In this stage, the temporary compromise between market and social/environmental discourses was broken and corporate executives sought to realign climate initiatives with the dominant corporate logic of maximizing shareholder value. Examples here included declining corporate fortunes and new CEOs who promoted a ‘back to basics’ strategy, the shifting political context which unwound climate-focused policy measures like the Clean Energy legislation, new fossil-fuel related business opportunities, and the dilution of climate initiatives within broader and less specific ‘sustainability’ and ‘resilience’ programs. As one senior manager in a major insurance company acknowledged: ‘Look, that was all a nice thing to have in good times but now we’re in hard times. We get back to core stuff’.

Our analysis thus highlights the policy limitations of relying on market and corporate responses to the climate crisis. We need to imagine a future that goes beyond the comfortable assumptions of corporate self-regulation and ‘market solutions’, and accept the need for mandatory regulation of fossil fuel extraction and use. In an era in which neoliberalism still dominates political imaginations around the world, our research thus highlights ‘an inconvenient truth’ for political and business elites; the folly of over-dependence on corporations and markets in addressing perhaps the gravest threats to our collective future.

Figure 1. The three stages of the translation process

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the authors’ paper An Inconvenient Truth: How Organizations Translate Climate Change into Business as Usual, Academy of Management Journal, October 2017

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Financing Climate Change, by ItzaFineDay, under a CC-BY-2.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Christopher Wright is Professor of Organisational Studies at the University of Sydney Business School and is the co-author, with Daniel Nyberg, of Climate Change, Capitalism and Corporations: Processes of Creative Self-Destruction.

Christopher Wright is Professor of Organisational Studies at the University of Sydney Business School and is the co-author, with Daniel Nyberg, of Climate Change, Capitalism and Corporations: Processes of Creative Self-Destruction.

Daniel Nyberg is Professor of Management at the University of Newcastle Business School. He researches how societal phenomena such as climate change are translated into local organizational situations.

Daniel Nyberg is Professor of Management at the University of Newcastle Business School. He researches how societal phenomena such as climate change are translated into local organizational situations.