How many social media profiles do you have? Do you feel that you express yourself accurately through these profiles? Do they reflect who you are? And who are you in the first place? Are you always the same? Do you present yourself the same way at different times and on different social media?

Profile making has become ubiquitous in digital society. We are regularly invited, and often required, to create profiles for many digital services; online banking, gaming sites, dating apps and social media platforms. Even as academics, we are encouraged to create profiles on sites such as Academia.edu and ResearchGate. Moreover, technological innovations, especially developments in smartphones, allow us to be ‘always on’, constantly checking these profiles and sharing ever more kinds of information; photographs, live videos and geolocation tags.

Our profiles, ourselves

Profiles are about identities, how we present and express ourselves online. Compared to traditional media such as press, radio and television – where only a limited number of people have been able to present themselves and represent others – the many-to-many nature of digital media has worked as an equalising force and allowed a greater number of people to present and express themselves without relying on intermediaries.

But can we really craft our online selves as we please? One limitation to the possibilities for self-presentation on social media is the very design of profiles. On Facebook, for example, we can choose our own main and cover photos, but why is it necessary to have a profile and a cover picture in the first place? Facebook has simply designed it this way, subtly suggesting that this is how we should present ourselves in this digital environment. Likewise, Instagram, which belongs to Facebook, suggests we should present ourselves in square photos and Twitter, in short text messages up to 280 characters.

This logic extends to rules about what we can post on social media – for example, terms of service and community guidelines – which serve to limit how we can present and express ourselves through profiles. Some of them are based on widely shared values, such as the ban on hate speech. Others are more arbitrary, like the censorship of some photos with female, but not male, nipples on Facebook and Instagram. Tumblr too has banned photos with ‘female-presenting nipples’, setting a different environment for the presentation and expression of the self for female-presenting and male-presenting people, not least the confusion of all those between and beyond the female-male binary.

Datified selves

Because social media platforms are commercial companies, the main factor influencing how they are designed and governed is profit. With the rise of data analytics, social media companies have been making most of their profits from targeted advertising based on the analysis of user data. In this way, the process of datafication drives the design and governance of social media platforms.

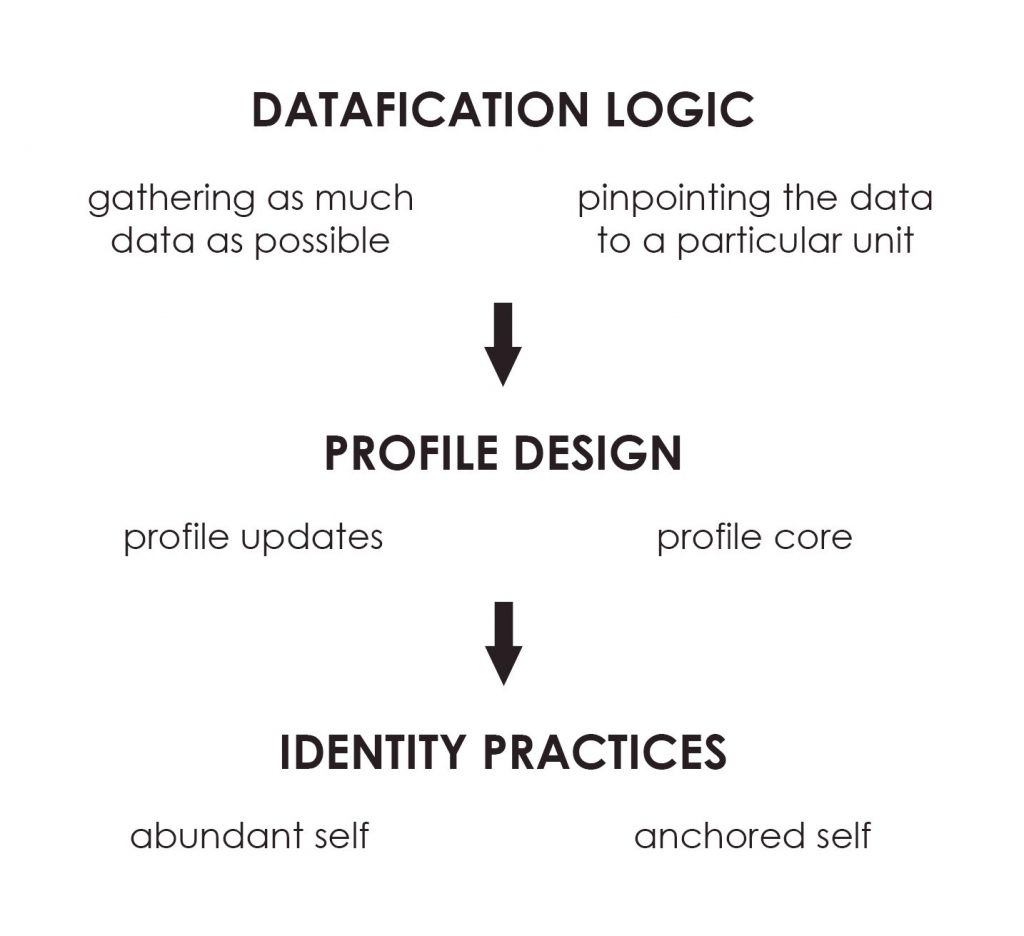

The underlying principle behind this business model is to collect as much data as possible and connect this data to particular users, while at the same time categorising users into more and less valuable targets for adverts. This principle is translated into the design of social media profiles, which usually consist of a constant stream of updates and a profile core. Finally, this design, together with the rules about how to use profiles, promotes particular ways of how we should present and express ourselves: to be capacious, complex and volatile (the abundant self) but, at the same time, singular and coherent (the anchored self).

Figure 1. How data-driven business model translates into identity practices

Abundant self

While the word ‘profile’ originally meant something concise, like an opening statement in a CV, social media profiles are also virtually endless streams of information about ourselves. When we use social media, what we see at the very centre of the screen is not only our profile core, but streams of updates, which of course are all data points used for targeted advertising. Further, social media platforms also actively encourage us to provide more updates, to explicitly present ever more details about ourselves and, hence, to create more data. They do it, by using prompts such as ‘What’s on your mind?’ (Facebook) and ‘What’s happening?’ (Twitter).

Analysis of data is also used to generate yet more data. Algorithms analyse profiles not only to show us personalised adverts but also to suggest us other profiles – be it users, fanpages or events – with which we are most likely to connect. In this way algorithms work to maximise the abundance of our digital connections, which create new data about ourselves and add to our already capacious digital selves.

Anchored self

The abundance of data produced through social media profiles would be of much less value if it was not possible to anchor the data, to pinpoint it to a particular user. Therefore, before the entire machinery of stimulating data production is set in motion, social media users are required to identify themselves by creating an account. Facebook also requires in its ‘Terms of Service’ that we ‘create only one account’, which helps the company to construct our detailed customer profile. However, this can pose problems for vulnerable Facebook users, for example LGBTQ refugees who prefer to create two Facebook profiles for reasons of privacy and safety.

From the perspective of a data-driven business model, it would be ideal, if we had one profile, not only on a particular social media platform, but also across platforms. Imagine what kind of customer profiles could be constructed about ourselves, if the data from our different profiles were combined. This is already happening. Facebook, for example, tracks how we browse the web through cookies and encourages us to use its profile to log in to other digital services including Instagram, Pinterest, Netflix, Spotify and Tinder. Facebook aims to convince us that such a ‘super meta profile’, ‘makes it easier for you to take your online identity with you all over the Web’, omitting the fact that it also makes it easier for Facebook to collect more data about us and more difficult for us to present and express ourselves differently across different social media.

Against the data straitjacket

Celebrating the new possibilities that digital media have given us to present and express ourselves, should not also prevent us from reflecting on their limitations and why these limits are imposed. Through data analytics, social media platforms use our profiles to profile us. They encourage us to be a lot and one at the same time, to constantly share ever more details of our lives that could be combined into a single customer profile. Crafting our abundant and anchored selves in accordance to this datafication logic may work well for some of us, at some times. We may like to express a lot of information about ourselves and it may be more comfortable for us to use one profile to log in to other social media, rather than creating yet another profile. However, when datafication logic becomes an unwritten fundamental principle behind our digital selves, it turns into a straitjacket, as in the case of some LGBTQ refugees, which stifles the more fragmented and contradictory ways in which we might prefer to present and express ourselves in different digital environments and for different audiences.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post appeared originally on LSE Impact. It is based on the author’s article ‘Profiles, Identities, Data: Making Abundant and Anchored Selves in a Platform Society’, recently published in Communication Theory.

- The author thanks Jędrzej Niklas and the editor for their comments on the draft of this article.

- The post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Antoine Beauvillain on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Lukasz Szulc is a lecturer in digital media and society at the University of Sheffield’s department of sociological studies, as well as a Marie Curie research fellow in LSE’s department of media and communications. His interests include cultural and critical studies of media in relation to identity, specifically focused on sexuality, nationalism and transnationalism. He recently published the book ‘Transnational Homosexuals in Communist Poland: Cross-Border Flows in Gay and Lesbian Magazines’(2018, Palgrave) and the chapter ‘Banal nationalism in the internet age: Rethinking the relationship between nations, nationalisms and the media.

Lukasz Szulc is a lecturer in digital media and society at the University of Sheffield’s department of sociological studies, as well as a Marie Curie research fellow in LSE’s department of media and communications. His interests include cultural and critical studies of media in relation to identity, specifically focused on sexuality, nationalism and transnationalism. He recently published the book ‘Transnational Homosexuals in Communist Poland: Cross-Border Flows in Gay and Lesbian Magazines’(2018, Palgrave) and the chapter ‘Banal nationalism in the internet age: Rethinking the relationship between nations, nationalisms and the media.