Ever since the United Kingdom decided to leave the European Union in June 2016, one question has been on the minds of many Europeans: which other member states could leave the EU in the years ahead? In fact, one argument among Brexiteers in the run-up to the referendum was that the UK needs to break free from the EU as a ’failing political project’, a mantra repeated by Leave supporters to this day. But how likely is it that the EU will fail?

In a recent paper, I argue that there are essentially two scenarios in which the EU could collapse. The first entails all EU member states agreeing – unanimously – to change the Treaties and dissolve the EU. This is, perhaps self-evidently, never going to happen since there will always be states opposing this course of action (e.g. Luxembourg). The second scenario is the EU being hollowed out by successive – but individual – exits of member states, which each state can decide on a sovereign basis within its own domestic political arena.

This second option cannot be discarded out of hand. The UK ’successfully’ leaving the EU will demonstrate that it is just that – an option for member states. In fact, many states have already been linked to future exits, as this picture brilliantly summarises. To get a better understanding of how much of a threat this really is for the EU, I develop an ’exit index’ to measure each member state’s propensity to leave the EU.

The approach underpinning the exit index is simple. I look for indicators in the social, economic, and political dimensions that help us develop a better sense of how likely future exits are. For example, in the social dimension, it seems clear that the greater the share of citizens having only a national (and no European) identity, the more plausible an exit scenario is. Economically, the share of exports going to other EU member states (and thus the value of membership of the single market) promises to be a good indicator. Politically, the share of Eurosceptic MPs goes, among other factors, into the exit index.

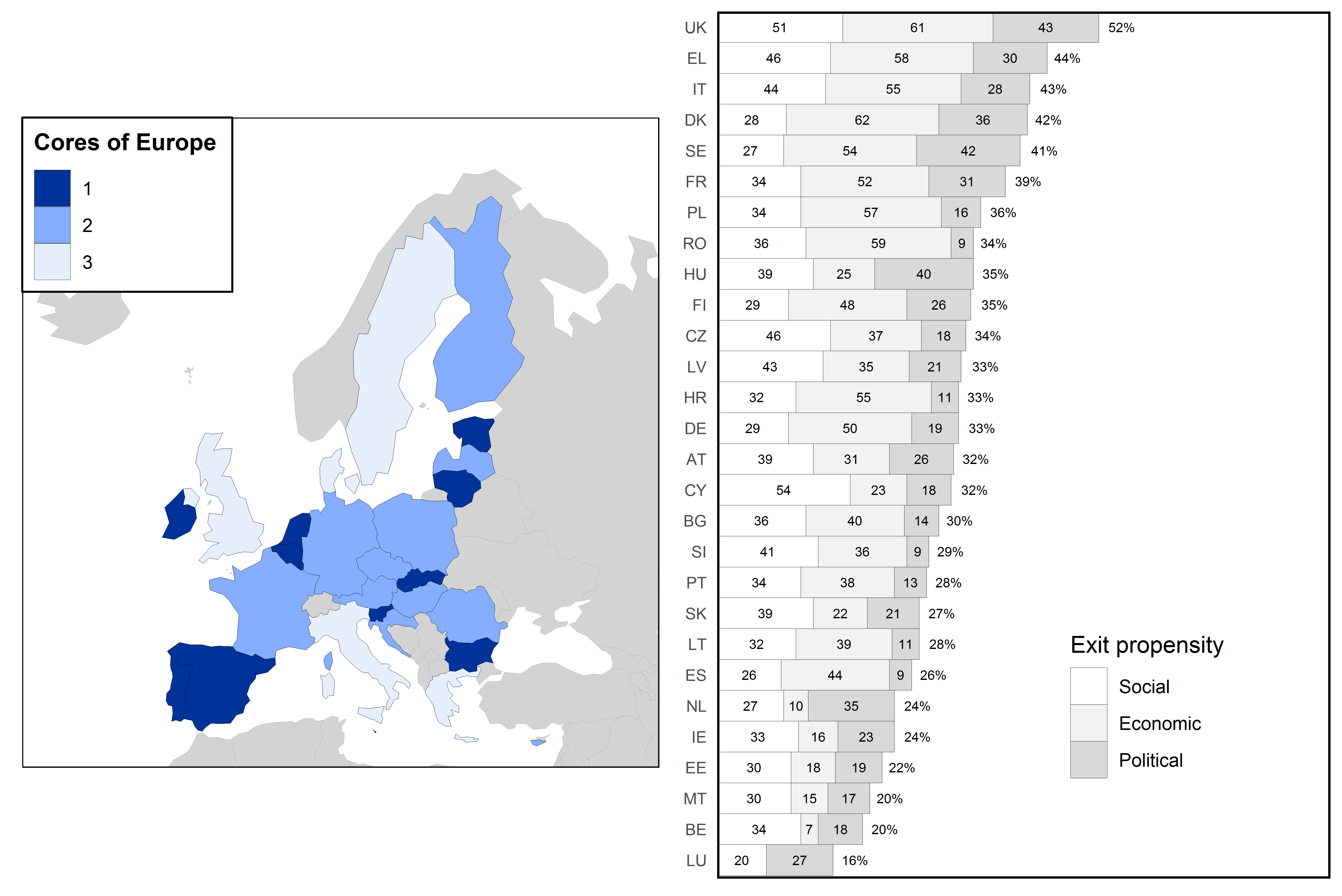

My findings can be summarised in two figures. Figure 1 shows the situation before the Brexit referendum (so around 2016). As can be seen in the table on the right, the UK really was uniquely positioned to leave the EU. It was also the only country ranking in the top three in each dimension individually. If we understand these dimensions as necessary conditions, where countries only leave the EU if ‘doing well’ across all three, no other member state faces a comparable risk of leaving the EU.

The exit index also allows us to define ’cores of Europe’. Core 1 states are extremely unlikely to leave the EU. Note, for example, that Ireland clearly falls into that category. Core 2 states are very unlikely to leave, but more likely than core 1 states. France and Germany, for example, belong to this core. Core 3 states are most susceptible to a leave vote. Unsurprisingly, Greece and Italy can be found in this core. However, even in core 3 the default expectation remains EU membership for all states but the UK.

Figure 1. Exit propensities before the UK’s EU referendum Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper

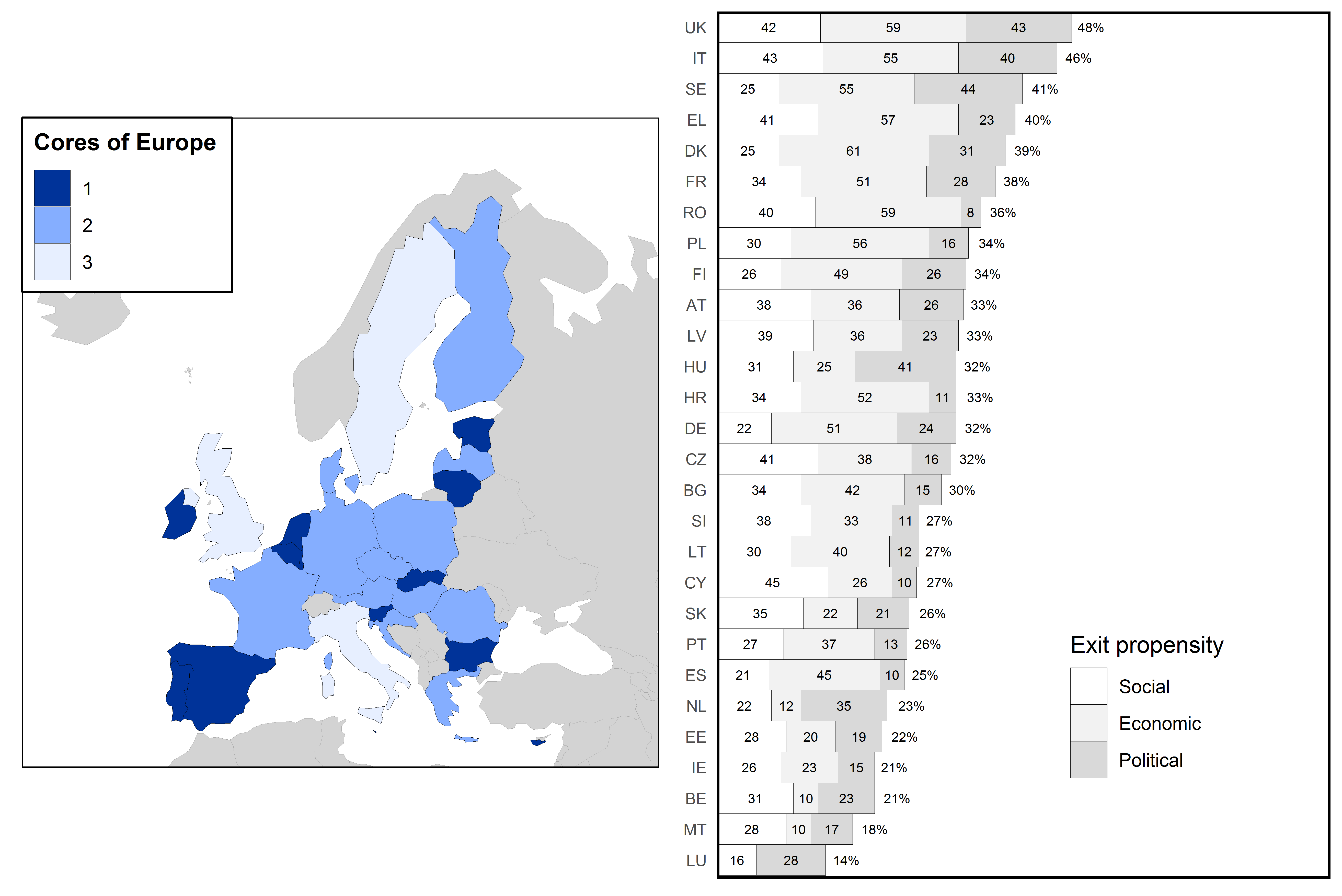

Figure 2 shows how the situation has changed since the referendum. These numbers also ’simulate’ Brexit by excluding the UK from intra-EU export figures. Overall, the EU has moved closer together. The only country really edging closer to an exit scenario in the past three years has been Italy. However, only 39 per cent of Italians lack a European identity. For comparison, the UK hit a whopping 63 per cent before the (narrowly won) referendum. Moreover, Italy would face massive economic adjustment costs from leaving the Eurozone.

Figure 2. Exit propensities after the UK’s EU referendum

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper

Importantly, Germany is far from abandoning the European project. Given its size and geographic centrality, it can be viewed as the linchpin of European integration. As long as Germany remains in the EU, it seems unlikely that other member states will see their national interests served by cutting ties to Brussels (and thus, to a significant extent, also Germany). France is somewhat more susceptible to an exit scenario, but the French also have a rather pronounced European identity and would face great difficulties in abandoning the euro. With France and Germany all but assured to stay in the EU, it is hard to imagine a plausible scenario where many (if any) member states would prefer to leave.

It is also interesting to note that the situation in the UK itself has changed significantly since the referendum. With 51 per cent, a slight majority of its citizens feel partly European today (compared to only 37 per cent before the referendum). Also, immigration from other EU member states is viewed in a more positive light. Today, 70 per cent feel positively about EU immigrants (compared to only 53 per cent around 2016). What is surprising then is that the share of respondents seeing a better future for the UK outside the EU has even increased slightly. One way to interpret this disconnect is that the British do see a better future outside the EU not because of issues connected to the EU itself anymore, but to finally put an end to the domestic political battle that has ravaged the country ever since the Brexit referendum has taken place.

All in all, the EU is in – perhaps surprisingly – good shape with few indications of other member states following the UK’s example and trading EU membership for a more than uncertain future. If anything, the political and social fallout after the Brexit referendum had the opposite effect and brought the remaining EU member states closer together. Describing the EU as a ’failing’ political project, therefore, is a serious mischaracterisation. This also underlines that the UK will need to define a future relationship with the EU as a whole in phase two of the negotiations, which will begin after the UK has ratified the withdrawal agreement and formally left the EU.

While it is perfectly understandable that people across the UK suffer from ‘Brexit fatigue’ and want to ‘get Brexit done’, the sad truth is that Brexit will remain a major topic – on both sides of the Channel – for years to come. The most important thing is that, during this long period of hard bargaining among neighbours, everyone in the UK and all across the EU remembers that there will always be so many more things that unite than divide us. An adversarial relationship based on loose ties serves no one in the long term.

♣♣♣

- This blog post appeared originally on LSE Brexit. It is based on Brexit! Grexit? Frexit? Considerations on how to explain and measure the propensities of member states to leave the European Union, EUI Working Papers, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, 2019/85.

- The post gives the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Featured image by European Parliament, under a CC-BY-2.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Markus Gastinger has a PhD from the European University Institute and is currently a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellow at the University of Salzburg, Austria. He tweets @MarkusGastinger

Markus Gastinger has a PhD from the European University Institute and is currently a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellow at the University of Salzburg, Austria. He tweets @MarkusGastinger