The Covid-19 outbreak encompasses health risks and difficulties to our food chains. Above-normal demand and hoarding of some basic products have affected the normal operation of the food supply chain, resulting in empty supermarket shelves and forcing some retailers to impose constraints on the quantities sold. These impacts have increased food insecurity for the most vulnerable groups in the country.

How do food supply chains operate?

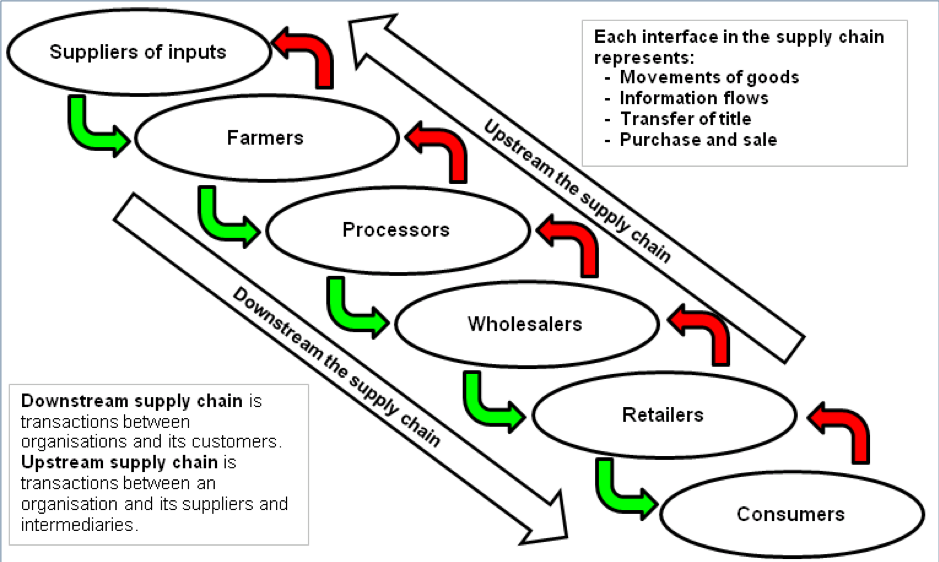

Figure 1 below shows a representation of the supply chain of an agri-food product such as ketchup or a dairy product such as milk. The actual stage depends on the product. Some, such as domestically-produced vegetables, are relatively simple. Others are amazingly complex, given that ingredients of the final product, such as flavours, may come from different parts of the world. Large modern supply chains, such as the one behind our retailers, are organised by detailed contracts, where information about the product — such as quantity, quality, price, and place of delivery — is clearly stipulated. Hence, any change in the specification can be significantly disruptive.

As shown in Figure 1, whilst goods flow downstream the supply chain, information flows upstream from the end of the chain. This includes consumer preferences, or any relevant change in taste. Contracts from customers, such as retailers, allow the different parts of the upstream chain to plan the inputs that they require.

Figure 1. The supply chain of an agricultural product

How are supply chains organised?

Food supply chains have evolved over time and are designed for the pursuit of efficiency (i.e., providing the same or improved services at lower costs). In a modern world where tastes change rapidly, it is inefficient to have much of a product in stock. Having minimal stocks also helps to spot quality problems with products. As a result, retailers tend to adopt just-in-time (JIT) and build-to-order (BTO) supply strategies. These strategies have been developed to provide a near‐instant supply of the precise products demanded between businesses. That is possible thanks to the transmission of information along the chain to reach a high level of market coordination.

Although modern food supply chains are designed to cope with variable demand, JIT and BTO strategies are not able to significantly increase the quantity they supply in the short term if there is a large surge in demand within a very short time, like the one that we have recently observed. This does not mean that the supply chain has stopped producing the food required. It has and will continue doing so at the maximum capacity that its organisation allows, which implies that the inventories along the chain will be minimal as they will be used to serve the higher demand.

Labour shortages an additional constraint

Additional food supply chain issues are created by the labour shortages caused by Covid-19 (either due to illness or self-isolation). This affects every stage of the chain and necessarily makes it less flexible. Consider, for instance, the case of a logistics system with fewer truckers available to deliver food within a JIT system. Also, and mostly unrelated to the virus, a lack of migrant labour in some parts of the chain, such as in agriculture, reinforces the problems.

Why do we see empty shelves in supermarkets?

The surge in consumer demand is a combination of at least three different factors:

First, demand increase, given that meals have been reallocated from food services, like restaurants and canteens, to household consumption. That causes a change in demand patterns.

According to the latest figures of Defra’s Family Food (2017/18), total food expenditure outside the home in the UK is £13.9 per person per week, whilst the expenditure for household supplies is £31.4 per person per week. If the lockout is perfect, and all the meals are taken at home (all the money is still spent on food), it implies a maximum average increase in demand for household supplies of around 44%, which is quite significant and unprecedented by any standard. This is an average figure. Some people have more money to spend than others. Since they’re not eating out, the first income decile (least purchasing power) would be able to spend 24% more on their household food items, whilst for the group with higher purchasing power (top decile) it would be 66%.

Second, new social distancing requirements might cut down the frequency of trips to the supermarket, and therefore, individuals increase the size of their purchased baskets, and engage in stockpiling, to prevent potential future dispersion.

Third, consumers’ panic due to a combination of media coverage and the language used (labelling the crisis as a ‘war’).

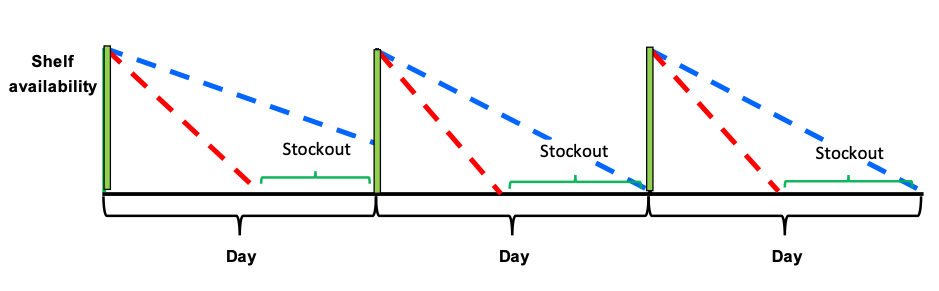

Figure 2 reports the availability of food in three consecutive days under two situations: ‘normal demand’ (blue dotted line) and ‘current demand’ (red dotted line). Every day the supplies are replenished (represented by the thick green bar) at the beginning of the day and they decrease depending of the demand. ‘Current demand’ is well above ‘normal demand’. This generates daily stockouts and explains the apparent contradiction that we hear in the news: on the one hand, people complaining of a lack of products and, on the other hand, commentators from the industry insisting that there is enough food in the supply chain.

Figure 2. Availability of food supplies at a supermarket in three consecutive days

One should point out that running to the supermarket and stockpiling food, in the UK and elsewhere, are natural reactions of consumers in individualistic cultures, as reported recently in Prospect magazine, even attempting to take advantage of future scarcity by selling hand gels well above market price .

Finally, Covid-19 has led to a shift in demand towards non-perishable basic food items such as pasta, rice, UHT milk, canned food, canned meat and frozen food. The change in the focus of people’s expenditures unavoidably affects suppliers of products that are not the main priority.

How can supermarket chains deal with this situation?

As shown in the news, the rise in food demand and consequent stockouts are creating accessibility issues for some people who, for several reasons, cannot go around trying to find food. The Grocer reports that supermarkets are taking the lead implementing different actions to improve the accessibility to food for people. Some of the measures are:

- Limiting the number of products that can be purchased.

- Asking suppliers to simplify ranges to help increase production volume.

- Changing the opening hours and increasing the workforce.

- Expanding delivery hours and increasing the click-and-collect points because the current online infrastructure cannot cope with the abrupt increase in demand. This helps only with the delivery part, because both online and offline retailers depend on the same suppliers.

- Helping small suppliers affected by lower demand.

Product travel restrictions

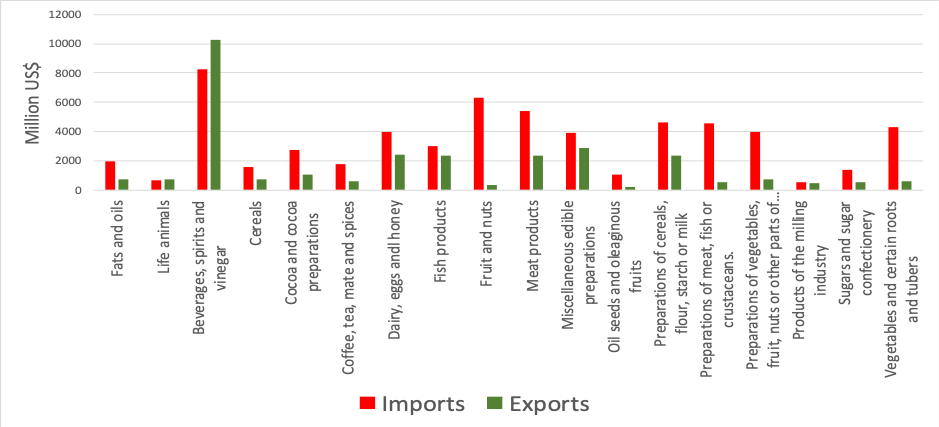

As trade is disrupted by travel restrictions and border closures, food and drink supplies are inevitably affected. Figure 3 below summarises the 2019 UK food imports and exports. It shows several categories where imports are higher than exports, showing some dependency on imports. A large share of this trade is with EU countries. Being part of the single market helps ensure food availability. However, suppliers within the EU are facing the same challenges as the UK, and their supply can potentially be disrupted. An example of this is pasta, which is facing production issues in Italy (The Grocer, 2020).

Figure 3. UK food trade values, 2019

Source: UN Comtrade

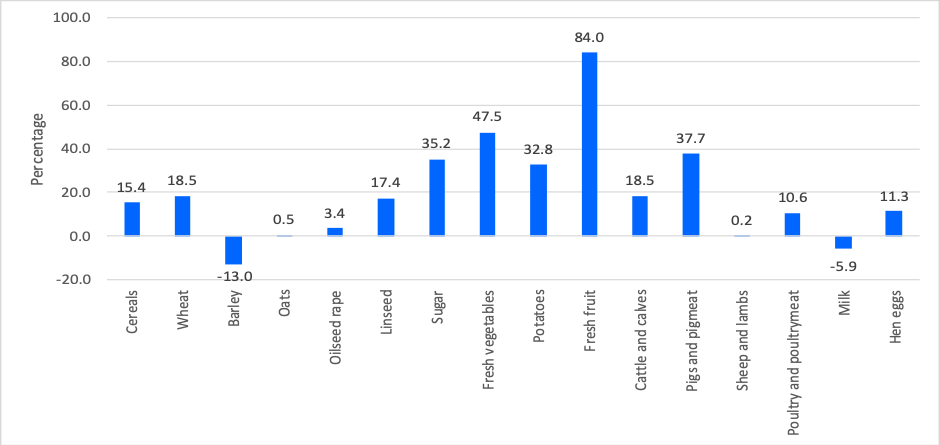

The figure below illustrates the UK’s needs of imports for basic agricultural products. It shows the country’s dependency on imported fresh fruits and vegetables (84% and 47.5%).

Figure 4. UK self-sufficiency of major agricultural products, 2018

Source: Defra. Agriculture in the UK. Note: Negative percentages indicate complete self-sufficiency.

Travel restrictions might lead to lower consumption of products imported from around the world. UK food exports might be restricted. Depending on the time scale of this pandemic, this change might result in a change in consumers’ demand towards more local and seasonal foods, and a change of suppliers’ commercialisation strategy.

Access to food by the most vulnerable

The surge in demand has the effect of breaking the synchronisation and stability of the material flows across the food chain, with the most visible consequence being empty shelves in all supermarkets. As a knock-on effect, a disrupted food chain can exert a differential impact on the most vulnerable in society. Not only do they face a reduction in income, but stockpiling might be increasing their food insecurity and reducing the availability of goods in food banks. According to the Trussell Trust, food banks depend on the donation of non-perishable in-date food by the public at a range of places, such as schools, churches and business, as well as supermarket collection points. In addition, many food bank volunteers are asked to self-isolate, which weakens those needed institutions at the worst times.

What support is needed?

Supermarkets need support to find the human resources needed in no time, and to overcome product travel restrictions. The UK government should be more forceful in making people aware of the social consequences of stockpiling, and it should protect parts of UK society from becoming food insecure.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Stephen West, under a CC-BY-2.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Montserrat Costa-Font is the programme director for the MSc in food security at the University of Edinburgh, and a food supply chain economist at Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC).

Montserrat Costa-Font is the programme director for the MSc in food security at the University of Edinburgh, and a food supply chain economist at Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC).

Cesar Revoredo-Giha is a senior economist and food marketing research team leader, and a reader in food supply chain economics at Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC).

Cesar Revoredo-Giha is a senior economist and food marketing research team leader, and a reader in food supply chain economics at Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC).

Una muy buena relación de los consumidores y estudio de la facturación de alimentos con graves problemas!!! Debe ser resuelto como indican los autores!!!

It is a great worry that councillors have insufficient understanding about the importance of good quality farm land for food security that they think can be sacrificed for housing. A food crisis would be far more serious than a housing crisis. The U.K needs a clear policy to protect all farm land capable of producing food that we import, or our food security will worsen.