The European Commission is often criticised for being too distant from EU citizens and for proposing policies without adequately taking on board the views of ordinary people. But how accurate is this criticism in reality? Drawing on recent research, Christian Rauh argues that the Commission is far more responsive to public opinion than is commonly recognised.

The European Commission is often criticised for being too distant from EU citizens and for proposing policies without adequately taking on board the views of ordinary people. But how accurate is this criticism in reality? Drawing on recent research, Christian Rauh argues that the Commission is far more responsive to public opinion than is commonly recognised.

In Eurosceptic discourses, ‘Brussels’ is often portrayed as the source of unpopular policy. The European Commission in particular serves as a spectre of remote, detached, and elitist decision making that prays to specialised lobbies, but has lost touch with the wider citizenry.

Yet, how does this go together with the intensifying public politicisation of European integration? Recent decades have seen several periods in which the public visibility of European politics has increased markedly, public opinion has become diversified, and political demands on Brussels’ policies have been mobilised to great effect.

Brexit and the failed Constitutional Treaty are just two examples of the way that such politicisation has challenged the notion of a further concentration of political authority in Brussels. Given the events of the last 10-15 years, is it still reasonable to assume that the Commission can ignore the wider citizenry when devising its policies?

A responsive technocracy

In a recent book, I argue that it is not. If a high level of general EU politicisation goes hand in hand with strong public attention to a given draft regulation, the Commission has clear-cut incentives to care about the public appeal of the proposed laws. Trying to garner – or at least not to undermine – public support for European integration, it will put a premium on policy choices that explicitly benefit widely spread societal interests.

European consumer policy – one of the fastest growing areas of supranational activity – is a pertinent testing ground. Here, the Commission has traditionally undermined national consumer protection, thus serving the interests of cross-border commerce. However, choices in this field also affect the direct interests of almost 500 million consumers in the EU. Intensifying EU politicisation should make this stakeholder group much more important, which would then be observable in the actual distribution of rights and risks the Commission proposes.

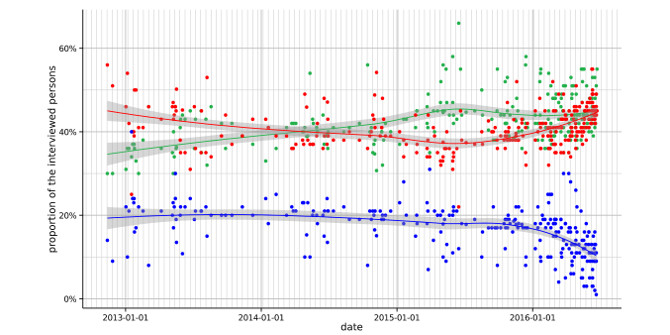

I thus compared 17 Commission consumer policy initiatives between 1999 and 2008 by relying on internal documentation, stakeholder position papers, and a range of interviews with involved officials. The drafting processes were re-constructed against indicators for the general level of EU politicisation – measured by the EU’s newspaper visibility, the polarisation of public opinion, and the number of public protests – and media attention to contractual consumer rights, product safety, and food safety. Two brief examples from this research outline how politicisation and issue salience actually lead the Commission to more consumer-oriented positions.

Politicisation, issue salience, and consumer policy choices

One example, now advertised at each and every European airport, is the 2001 initiative on air passenger rights. Against public criticism of poor customer service in air transport, the Commission Directorate General (DG) Transport and Energy launched an information campaign in the late 1990s. It was initially not meant to lead to a binding law, but earned a great deal of media applause and stepped up public pressure on the airline companies.

The companies, in turn, promised better service and less overbooking in a voluntary agreement in May 2001. However, shortly thereafter, persistent reports of overburdened air traffic coincided with an unprecedentedly lively general discussion on the EU – at issue was ratification of the Nice Treaty; at the same time protests against globalisation took a violent turn on occasion. In this atmosphere, DG Transport seemed no longer satisfied with a voluntary industry agreement and suddenly put forward a surprisingly far-reaching law proposal that, amongst other things, would quadruple compensation for consumers affected by overbooking. At a time of high public attention to the issue area and a strong overall politicisation of the EU, this strong signal for market intervention in the name of European consumers was more than welcome.

A similar example is the revision of the Toy Safety Directive. Its predecessor had been a flagship of the so-called new approach in European product regulation, which minimised government intervention and left the elaboration of safety standards up to industry representatives. DG Enterprise and Industry, which was responsible in this field, strongly defended these fundamental principles, partly to get a grip on a smouldering turf conflict with DG Health and Consumers. During the first five years of drafting, the basic parameters were never really called into question. It was only in the final months that things suddenly changed.

While the EU itself was in the headlines with negotiations on the Lisbon Treaty, in the summer of 2007, a number of toy scandals attracted public attention. Sweeping recall measures on Barbie dolls in several EU countries, for instance, focused the public eye on product safety in the European market. DG Health and Consumers took advantage of these events and propagated its consumer-friendly stance in various public communications. This, in turn, pushed DG Enterprise and Industry into some last-minute concessions.

Departing from the long-defended course, the final 2008 proposal required, for example, producers to anticipate every possible misuse of a toy. Compared with earlier versions, it also tightened the rules on chemicals, expanded labelling obligations, prohibited toys in food, and, by cross-reference, made the markedly more restrictive product safety rules of the DG Health and Consumers applicable for the toy market. Again, consumer protection was increased only when both the EU in general and the subject matter in particular figured prominently on the public agenda.

Commission policy: wherever the wind blows?

The pattern also holds for a range of other policies; for example, on consumer loans, nutrition and health claims, or unfair commercial practices, in which progressive British consumer law has provided particularly useful templates. However, pandering to the public is, of course, only one concern of the Commission.

My research also underlines (once more) that extant European law and anticipated majorities in the Council of Ministers, as well as internal coordination and conflict, effectively constrain proposed policies. But, in the remaining leeway, the chosen options back the view often expressed by the officials themselves: when European integration comes under public scrutiny, the Commission makes a particular effort to win public support for Europe through the content of its initiatives.

Thus, the ‘technocrats in Brussels’ are apparently not as isolated and out of touch as is often assumed; they demonstrably react to public debates. Public politicisation also gives a voice to societal interests without a powerful lobby in Brussels. To publicly denounce deficiencies and ascribe political influence to the European Commission is a promising strategy precisely at times when Europe is once again a subject of fundamental controversy.

However, one must also be cautious about generalising based on the logic found in consumer policy. In this field, it is easy to predict which policy choices generate approval among the wider public. However, in other areas such as social policy or migration, the Commission faces much more heterogeneous preferences among the European citizenry. If such polarising issues attract a great deal of public attention, the model I have developed would instead predict that the Commission would hesitate to adopt a clear position at all.

Institutional mechanisms for channelling public attention and criticism into European policy are therefore advisable in the long term. The semi-successful experiment during the 2014 European Parliament elections to bind the top Commission staff to European voter preferences is a step in this direction. Yet, already without such institutional channels, public debates about Europe can provide a corrective to the hitherto highly technocratic decision making in Brussels.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: For more information on this topic, see the author’s recent book, published by ECPR press. This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: R/DV/RS (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2c6ptSK

_________________________________

Christian Rauh is a research fellow in the Global Governance department at the WZB Berlin Social Science Center. His teaching and publications focus on empirically analysing the public politicisation of governance arrangements beyond the nation state. More information on his work is available at his website or via Twitter.

Christian Rauh is a research fellow in the Global Governance department at the WZB Berlin Social Science Center. His teaching and publications focus on empirically analysing the public politicisation of governance arrangements beyond the nation state. More information on his work is available at his website or via Twitter.