On 26 January 2015, Alexis Tsipras, the leader of Syriza, took office as Prime Minister of Greece. But how successful has Syriza been in its two years in power? Myrto Tsakatika reflects on the party’s strategy, writing that Tsipras would have benefitted from having come into government with a more focused plan to shift the way the state apparatus works in Greece in a progressive direction.

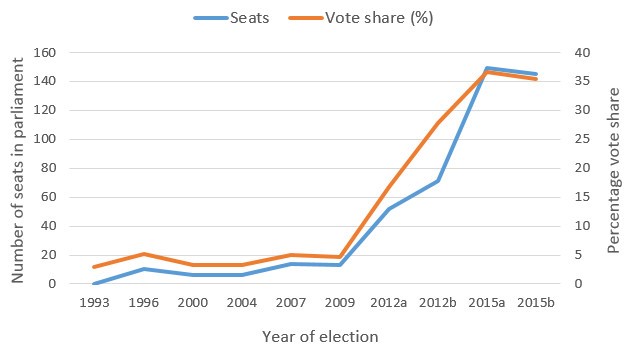

Before economic and political crisis hit Greece, Syriza was an electoral coalition between Synaspismos, a former Eurocommunist, democratic socialist party and a host of minor parties and groups of the European radical left whose vote share had stabilised at around 4 per cent. In the space of five turbulent years (2010-2015) Syriza replaced Pasok as Greece’s main party on the left and won three nationwide elections (as shown in the table below).

As explained in some recently published research, the party that today governs Greece built its electoral success on a strategy that combined anti-establishment protest and a left-wing populist discourse with a bid to take on responsibility for government based on the competence of its prominent left wing economists and the ‘moral advantage’ it could claim as a political force that had not been involved in the ‘clientelist spoils system’ that led the country to bankruptcy.

Figure: Results for Syriza and Synaspismos in national elections in Greece (1992-2015)

Note: Until 2000 the results refer to Synaspismos. Between 2004 and 2012a the results refer to the Syriza coalition of which Synaspismos was a founding member and main component. From 2012b onwards Syriza competed in elections as a unified party. Source: Greek Ministry of the Interior

Depending on one’s viewpount, Syriza’s coming to power was either heralded as a sign of the revival of radical left politics in Europe – termed by some observers as ‘Pasokification’, aka the punishment of social democracy for embracing the Third Way – or as yet another instance of the populist menace to democracy that was gaining support amongst Europe’s disillusioned voters, whether on the left or right.

But now that the party has been in power for a significant period of time, how is Syriza’s bid for government responsibility turning out? Is it challenging the status quo while slowly but surely building the foundations of an alternative left economic paradigm in Greece? Or is it struggling to maintain its character as a radical left party while trying to cope with the Troika’s requirements and finding accommodation with the Greek political and economic establishment? And what does the Syriza story say about other radical contenders that wish to challenge social democratic parties by claiming they can offer a distinct government alternative to the mainstream politics of the European centre-right?

Syriza’s strategy and record in office

The Syriza government has had minor successes, taking forward its plan for poverty alleviation, spreading out the burdens via more progressive taxation and stepping up efforts to collect taxes and combat tax evasion. It has improved access to healthcare for the most vulnerable. It has also implemented progressive legislation such as that involving the recognition of same-sex partnerships. It has begun to promote the development of the social economy sector and aims to target structural funding toward poorer regions and the generation of youth employment. Yet, the Greek economy is recovering at a very slow pace and foreign direct investment remains scant. Simultaneously lacking in infrastructure, experience in crisis management and significant resources, the government has struggled to cope with the influx of sixty thousand Syrian refugees that remain stranded in the country.

What is more, Syriza is short of allies. Regulating the TV landscape and getting media moguls to pay their dues to the state for operating licences has been set back by judicial review procedures that declared part of Syriza’s handling of the issue as unconstitutional. In the meantime, negotiations for debt relief with the Troika have continued without success and a fourth bailout agreement may soon be on the cards. The party itself is still trying to find its feet after the 2015 party split that saw it lose much of its activist base and links to social movements that had been developing throughout the 2000s. As a party of government, Syriza increasingly faces street protests by professional groups affected by structural reforms and increasing voter discontent.

The strategy that brought Syriza to power may well be its weakness while in government. Constantly confronted with its previous radical left and anti-establishment rhetoric, Syriza is having to make painful compromises at home and abroad. This is nothing new to political scientists who have long observed the dynamics of the moderating and centripetal pull of government. What calls for deeper analysis is how European left populist parties govern.

Syriza would have benefited from having come into government with a more focused plan to change the way the state apparatus works in Greece in a progressive direction and by strengthening its social alliances. ‘Moral advantage’ is a short lived advantage that cannot ultimately substitute for effective alternative policy solutions. Party strategists in Spain’s Podemos and Italy’s Five Star Movement would do well to ponder on these issues when deciding when the time is right to claim government responsibility.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article has also been published in Spanish at Agenda Pública in collaboration with South European Politics and Society. The article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Myrto Tsakatika – University of Glasgow

Myrto Tsakatika – University of Glasgow

Myrto Tsakatika is Senior Lecturer in Politics at the University of Glasgow.