In a recent study, Sara Hobolt and Thomas Leeper examined public opinion on various dimensions of Brexit using an innovative technique for revealing preferences. Their results suggest that while the public is largely indifferent about many aspects of the negotiations, Leave and Remain voters are divided on several key issues.

In a recent study, Sara Hobolt and Thomas Leeper examined public opinion on various dimensions of Brexit using an innovative technique for revealing preferences. Their results suggest that while the public is largely indifferent about many aspects of the negotiations, Leave and Remain voters are divided on several key issues.

Measuring public preferences is commonly approached through survey questionnaires, in which individuals express a degree of favour or disfavour toward a particular object such as a policy, product, political candidate, or – recently – possible outcomes of Brexit negotiations. When objects of evaluation have many features, such as preferences over trade, preferences over immigration, etc. entangled in current negotiations, it is common to ask about those specific aspects as separate questions. Evaluating the relative importance of the different features, however, becomes empirically challenging.

An alternative approach is “conjoint” experiments, in which respondents are asked to consider “bundles” of outcomes as a whole – that is, to consider a possible Brexit negotiation deal that includes a large number of different features as a complete package, with the specific features (e.g., the amount of immigration control) randomly varied. We recently conducted a conjoint experiment about the public’s attitudes toward Brexit with a total sample size of 3,293 respondents. It was fielded 26-27 April via YouGov’s online Omnibus panel.

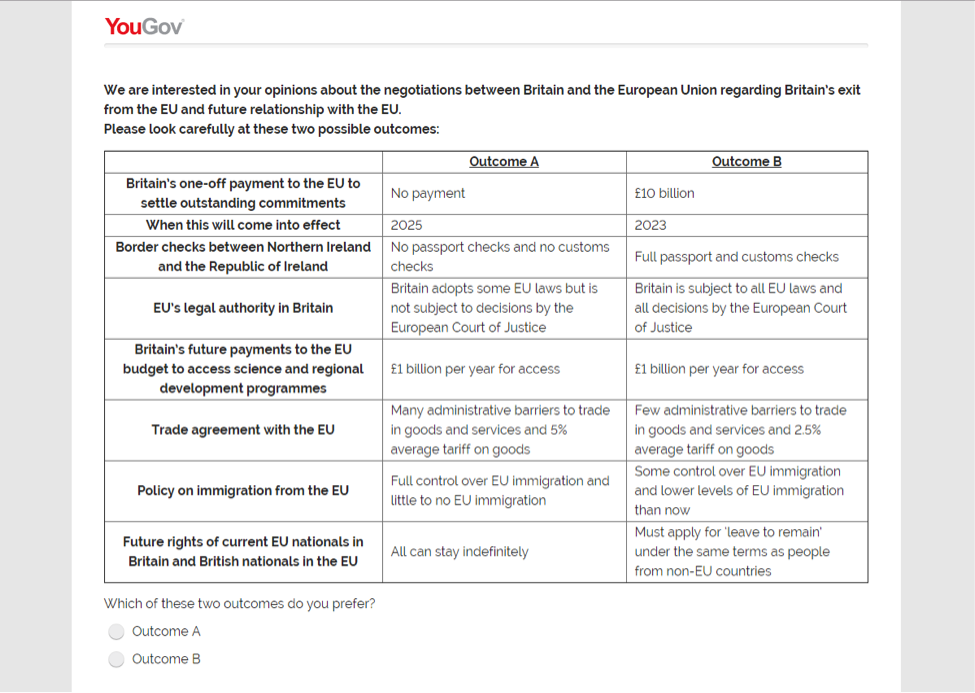

In our design, respondents were shown a series of possible Brexit negotiation outcomes in pairs and were asked to choose which one of the two that they liked best (there was no “don’t know” option). This requirement that they choose is crucial to the conjoint approach and to our results. A screenshot of what the respondents saw is below:

Conjoint experiments differ considerably from traditional public opinion surveys in a number of ways that make powerful tools for understanding preferences. First, they allow us to make comparisons between respondents’ evaluations of different bundles in order to detect the relative importance of individual features. Rather than asking respondents directly about each separate feature, we can allow their choices in these difficult trade-off scenarios to reveal the acceptability of different features. Our results, therefore, have to be understood as the preferences respondents hold over Brexit when all of the features of the negotiation are weighed together as a package. While this makes it difficult to compare our results to those of more traditional polling, we gain a considerable amount by asking respondents to engage directly with the difficult trade-offs involved in the negotiations.

Second, because the features that are shown to respondents are fully randomized in the design, we ensure that respondents do not infer or attempt to infer how different aspects of negotiations might be tied to others. For example, if we simply asked respondents about their preferences over trade policy, they are likely to make assumptions about what that might mean for immigration policy. In the conjoint, we provide information about both aspects (as well as others), thereby making any trade-off explicit rather than implicit. As well, in our design, we never use any of the most politicized labels from ongoing debate – such as “hard” or “soft” Brexit, or “freedom of movement”, “free trade”, etc. – but instead attempt to use more precise language to describe features of a possible deal.

Third, because each respondent is shown multiple pairs of trade-offs (six in our design), a conjoint design yields a very large dataset of revealed preferences, in our case just shy of 20,000 data points about what the public wants from Brexit. This gives us considerable statistical power to detect differences in Leave and Remain voters’ taste for various components of negotiations. The fact that the packages of negotiation outcomes shown to respondents consist of fully randomized combinations of features means that we can use straightforward mathematical (albeit perhaps confusing at first glance) procedures to measure those preferences.

Finally, a conjoint experiment allows us to present our results in two distinct ways. One of these describes the pattern of preferences in terms of levels and the other describes the pattern of preferences in terms of effects. Because respondents are forced to choose one of the two outcomes shown in each pair, we can draw out of the pattern of choices the proportions of respondents that would accept or reject outcomes containing a given feature (in light of the trade-offs between features and the strengths and weaknesses of the chosen negotiation bundle as a whole).

On this measure of levels, a feature scoring 100% means that respondents would always choose outcomes that included that feature, regardless of any other aspect of Brexit. For example, if the immigration policy “Full control over EU immigration and little to no EU immigration” scored 100%, the public would trade-off everything else to have that immigration policy in a bundle consisting of any other combination of features. If it instead scored 0%, it would mean the public would never accept this policy and would similarly trade-off everything else to avoid it. If, finally, it scored 50% that would mean that the public was largely indifferent – they would accept it 50% of the time and reject it 50% in light of other possible features of the negotiation. These are not unconstrained preferences as in typical polling, but instead patterns of opinions reflecting the inherent complexity of the decisions at hand. In other words, if forced to choose (and to choose possibly between unpleasant alternatives), what percentage of the public would accept or reject whole deals based on this particular feature?

The second way of presenting the results is as effects – in the statistical language of a conjoint design, an “average marginal component effect”. In this presentation, rather than highlighting rejection versus indifference versus support, we can convey the degree to which a given feature increases or decreases support for a bundle as a whole relative to a baseline deal. The meaning of the results are identical but are presented in a way that cannot be interpreted as percentages of the public that support a feature or a bundle of features. Instead, they are weightings of the importance of different features relative to a baseline combination of features – in our case, we treat a “no deal” exit of the EU as the baseline condition, so a positive effect can be interpreted as a given feature increasing support for a negotiation outcome that contains it and a negative effect can be interpreted as a given feature decreasing support for a negotiation outcome that contains it.

The Specific Survey Procedures

Our design followed the emerging paradigm for conjoint studies, entailing a number of features of Brexit negotiation outcomes, and the request that survey participants complete multiple discrete choice tasks. At the beginning of the study, participants completed a few brief background questions, with most demographic data being drawn from YouGov’s profile variables, and then completed five sequential conjoint profile ratings. Each conjoint task presented two alternative Brexit negotiation outcome scenarios (see figure above) and asked participants: “We are interested in your opinions about possible agreements between Britain and the EU regarding Britain’s exit from the EU and future relationship. Please consider the following two possible agreements.” They were then shown two outcomes that varied along eight dimensions. After that, they were asked “Which of these two outcomes do you prefer? (Outcome A; Outcome B)” and forced to choose one of the two.

The eight dimensions (attributes) were chosen to cover the most salient aspects of the Brexit negotiations. These features were: (1) immigration controls, (2) legal sovereignty, (3) rights of EU nationals, (4) ongoing EU budget payments, (5) one-off settlement, (6) trade terms, (7) status of the Republic of Ireland/Northern Ireland border, and (8) the timeline for Brexit. The levels were designed in such a way as to range between the two most extreme negotiation outcomes: a ‘ soft Brexit’ with continued British membership of the EU’s Single Market and Customs Union and a ‘ no deal’ scenario in which negotiations break down before an agreement has been reached.

The selection of levels of each feature for each profile was fully randomized, as was the order in which those features was presented in each table. This mitigates the risk of “profile ordering effects” wherein certain features are deemed more important because they are presented first or last in the table.

Our Results

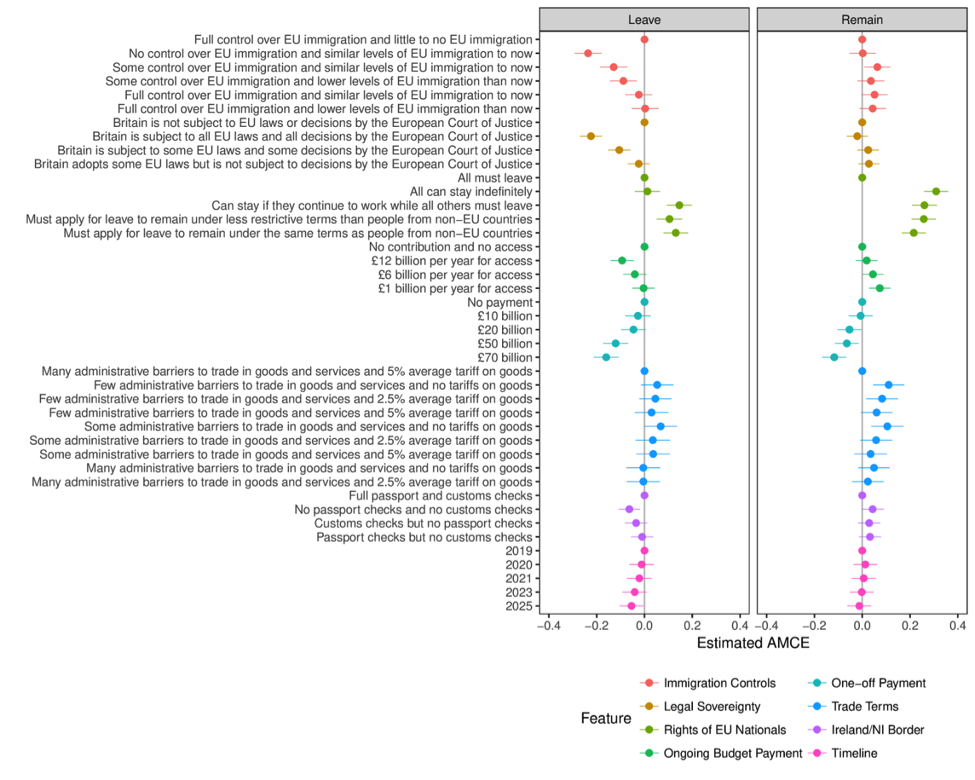

Starting with the presentation of effects, we express the effects against a baseline defined by the ‘no deal’ scenario in which Britain and the EU are unable to conclude an agreement on Britain’s exit. This means that there would be no trade deal, full legal independence of Britain from EU law and the European Court of Justice, no one-off or continuing payments to the EU budget, full control over immigration with no continuing EU immigration, the loss of rights of EU citizens currently residing in the UK, and a full (customs and passport) border between Ireland and Northern Ireland. Positive effects thus indicate support for ‘softer’ Brexit outcomes and negative values indicate opposition to those scenarios. The figure below presents these results separately for Leave and Remain voters, ignoring those who did not vote, based upon a measure of vote choice which was recorded immediately after the 2016 referendum. The lines around the point estimates are 95% confidence intervals.

Relative to the baseline of a ‘no deal’ exit, Remain voters favour alternative deals in every policy area except one-off payments to settle outstanding debts to the EU. They most favour a Brexit scenario that is ‘softer’ with respect to immigration, the rights of EU nationals, trade deals, ongoing budget contributions, and the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland.

Leave voters, by contrast, do not like any of these policy alternatives, except in areas related to the rights of EU nationals living in Britain and the nature of any trade deal. What people would like Brexit to mean therefore depends on how they voted in the referendum.

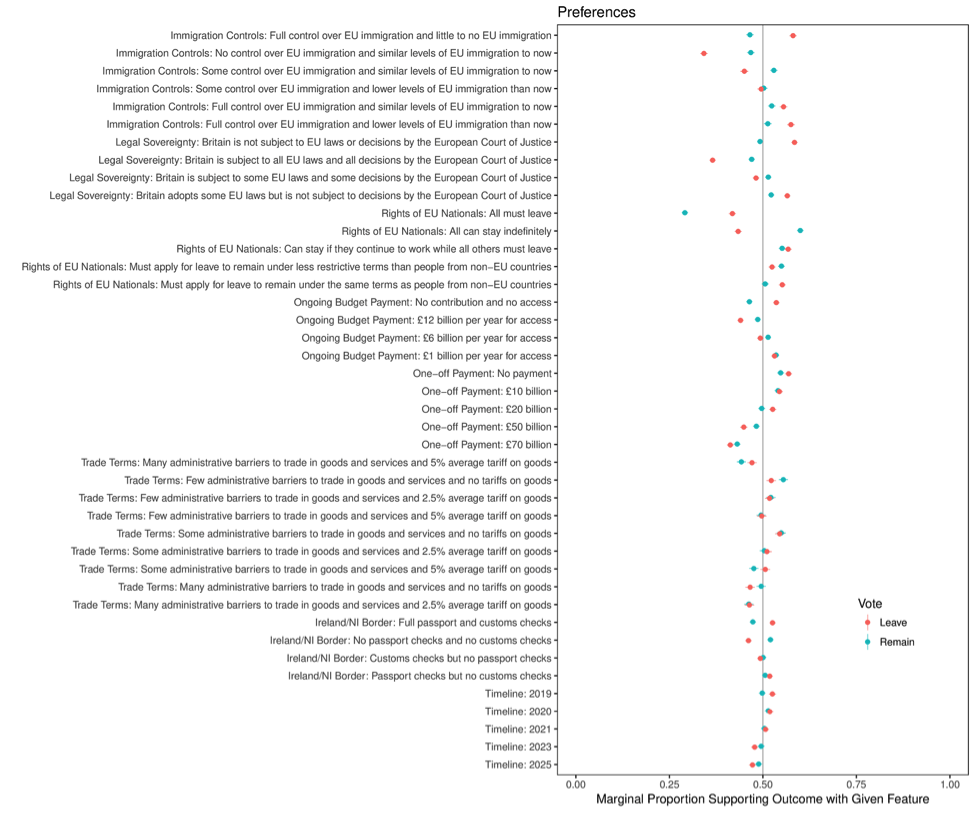

When we translate these results into levels, we obtain results that are mathematically identical to those above but that can be mapped out in terms of the proportions of respondents that would accept or reject outcomes that include each feature (see figure below). As should be immediately clear, most of the levels hover right around 0.5 (50%), meaning that respondents are largely indifferent about most of the aspects of the negotiations and the particularities of the deals. That said, there are some striking patterns of results (which will echo the effects analysis above).

Perhaps most striking is that few of the levels diverge particularly far from 0.5 (50%) toward either complete rejection (0%) or complete acceptance (100%). That means that for our respondents, most aspects of the negotiations are not sufficiently unacceptable to completely avoid at all costs nor are there aspects that are so important as to drive compromise of other features at all costs. The headline conclusions are therefore that the public is surprisingly willing to compromise on some aspects of the negotiations, even things that are arguably very important to them (as shown in the effects analysis above).

What we caution readers to avoid, however, is looking at these numbers as raw measures of support for particular features (as in conventional public opinion polling). This they are not. At no point did we ask respondent to evaluate individual features – they were only asked to make judgments of bundles of outcomes. The results we present are the preferences that are revealed by their choices between bundles. A value, for example, of 0.29 (29%) for Remain voters on “All must leave” does not mean – as it would in a typical polling context – that 29% of Remain voters favour all EU citizens having to leave to the UK.

Instead, given the design of our study, it suggests that 71% of the time, Remain voters would reject negotiations that contained that policy feature regardless of everything else it was bundled with and accept it only 29% of the time in light of everything else it was bundled with. When Leave voters score at 0.58 (58%) on “Full control over EU immigration and little to no EU immigration” that does not mean 58% of the Leave voters want no EU immigration but rather than Leave voters will accept negotiation outcomes containing that policy feature 58% of the time and reject negotiation outcomes containing it 42% of the time.

These somewhat complex interpretations, which require looking at the whole of our results together (not just the individual levels of support for specific items) and considering precise what task was given to our survey respondents, reflects the complexity of the task of negotiating the UK’s exit from the EU. When tasked with make difficult decisions involving complex trade-offs, what is acceptable and what is not? The answers aren’t always easy and what we see consistently is that the public – both Leave and Remain voters – are willing to make trade-offs.

Indeed, they appear to be almost completely indifferent over some aspects of the negotiations (such as the status of the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland and the timeline for agreeing any deal). It is not easy, as the government must now do, to make trade-offs between complex and interconnected aspects of Britain’s relationship to the EU. We designed our study to bring that complex decision-making to the public to measure their preferences in a new and different way from much other polling. Our results need to be read as a reflection of that complexity and the particular design we used.

While there appear to be few aspects of the negotiations that Leave and Remain voters demand at all cost or reject at all cost, there are aspects of the negotiations that are very important to them. Leave voters are particularly concerned about control over immigration and opposed to deals that give Britain less than “full control” over immigration. They are similarly concerned about legal sovereignty and any “divorce bill”. They also strongly prefer scenarios where EU citizens are able to apply for residence more than scenarios where all must leave. Remain voters care much more about the rights of EU citizens – indeed, no other aspect of the negotiations appears to matter more to them. They also agree with Leave voters that trade terms with fewer barriers and lower tariffs than a “no deal” scenario would bring are preferable to a hard break from the common market. Yet, ultimately, citizens are indifferent about many aspects of Brexit.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: A detailed technical report is available containing all information about our study design and analysis. This article was first posted at our sister site, LSE Brexit. The article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Sara Hobolt – LSE

Sara Hobolt is Sutherland Chair in European Institutions at the LSE European Institute.

Thomas Leeper – LSE

Thomas Leeper is Associate Professor in Political Behaviour in the Department of Government at the LSE.

The comment regarding computers can be applied to the above. “you put muck in you get muck out”

Most of the British public do not know that all UK treaties with the EU are unlawful. They don’t know because of government censorship. The press, and indeed yourselves, dare not discuss this fact.. Our most basic freedoms guaranteed by Magna Carta have been brushed aside. a writ for habeas corpus is now denied. The answers given by the public to your surveys must be flawed because the British public do not know the truth. Tell them why the EU treaties are against our common law and you will get a different answer.

get your meds first grumpy, then take a looong walk outside …

Sad not grumpy because people who make comments like yours are either dishonest or ignorant. I believe in the rule of law. The common law that should allow such as I to apply for a writ of Habeas Corpus where a whistleblower has been unlawfully imprisoned for trying to expose corruption. If you are a decent person you will ask for verification of what I write. If not you will add more silly comments.

maybe so, except that everything that transpires from your ramblings is not some kind of heroic prince of justice, but the mumbo-jumbo of a conspiracy nutjob

feel free to whine about victimhood all you want, but you historical revisionism and legal mythos is so far from present actuality as to make you ridiculously self-centered and ignorant

one thing I have learned with people of you, Jules, Karl … and he likes, is that there is absolutely no point in trying to engage them rationally for their misconceptions and ignorance.

it’s not that I have perfect knowledge, it’s simply that you guys formulate crackpot theories based on your bigoted prejudices.

any attempt to acknowledge the fantasies in your thinking has to be rebutted and swat away, unless you might also have to acknowlegde being yourself a qwack … as such reason and facts have no bearing on you

we can only hope to isolate you before you poison more minds, unfortunately reinforcing your victimhood paranoia in the process … truly a sad process

JT

“Starbuck, you now have written in a sensible erudite manner”

If you’re being sarchastic, it wasn’t obvious … ;(

Starbuck abused with:

“people of you, Jules, Karl … no point in engaging with them rationally for their misconceptions and ignorance.”

” you guys formulate crackpot theories based on your bigoted prejudices.”

“the fantasies in your thinking”

“acknowlegde being yourself a qwack”

“reason and facts have no bearing on you”

“we can only hope to isolate you before you poison more minds”

People like Starbuck not only misunderstand, fail to see reason or accept facts – they double down by deliberately misrepresenting the Leave case.

Sadly some of us have to correct them.

But it’s VERY hard trying to remain civil with some of them.

At last, a well-presented and nuanced analysis of Brexit instead of the usual binary, scare stories.

Starbuck, you now have written in a sensible erudite manner. What I said in my original post was accepted by 12 separate chief constables. I.e. that giving our sovereignty to a foreign state unless we have been defeated in a war, is treason. Edward Heath was blackmailed by the knowledge of his pedophilia and forced to sign the first treaty. What happened to the treason allegations?? They were sent to Bernard Hogan Howe who promptly submitted his resignation to Theresa May. She refused to accept his resignation and he branded the 12 Chief Constables as vexatious litigants.

So Starbuck, continue to live in your make believe world. You really cannot change history but you can do as you are doing and hide the truth from others who are too lazy or do not have the time to research the truth because it is so well hidden. I can prove what I state. Just ask for the evidence; but I doubt if you will because I suspect that you are an infiltrator with the emphasis on traitor.

“was accepted by 12 separate chief constables. I.e. that giving our sovereignty to a foreign state unless we have been defeated in a war, is treason”

taken out of context, such a claim could be agreed by many sensible person

EXCEPT THAT IS A DUMB FALLACY

you were arguing that the UK lost its sovereignty to the EU and therefore it was treason because the “people” had been betrayed. but the very Parliament, that is the expression of popular will and sovereignty, pubicly acknowledged THAT NO LOSS OF SOVEREIGNTY had happened as per its membership of the European Union

“Edward Heath was blackmailed …” and here you go again ranting about conspiracies and fantasies of your troubled mind … I mean, that’s the very reason I advised you to chill up because no sensible discussion can be dpne (no matter the disagreements) if one side is all about strawman and fantaisies. it ends up being about opinions, rumors and a wasteful copious amount of time-paradox toilet papers (ie: I can’t be arsed with your bigotry and useful idiocy)

To Starbuck and others. Read Edward Heath’s memoirs. In it he admits lying to parliament when he stated that there was no loss of sovereignty. He knew there was, because the Lord Chancellor, the highest law officer in the land, wrote in a letter to Heath that there would be a loss of sovereignty if he signed such as the treaty of Rome. Events since have proved that. There is a huge amount of European law that we are forced to accept which is against the wishes of the majority of British people.

What I see as more alarming is the censorship by our governments, who are themselve controlled, has been so thorough as to stop the subject of our constitution being discussed by the media.

Regarding Edward Heath’s pedophilia. The Chief Constable of Wiltshire’s own investigations takes Heath’s pedophilia beyond a conspiracy theory.

in one sentence you castigate Edward Heath as a traitor, in another sentence you exalt him as a wise all-seer … what does it say about you if not that facts have no bearing upon your knowledge, because you are just a myth believer : whatever tidbits of rumors or conspiracy that fits your paranoia is then celebrated as science

here is some reality-check :

the UK didn’t lose sovereignty when joining the EU, IN ANY MEANINGFUL WAY because

1) even actions that seemed “imposed” on her, actually had both the tacit approval of parliament and was in her interests (as acknowledged by ministers and MPs, not the rabid Rees-Mogg/Bone likes ofc)

2) even before accession, “sovereignty” was more a theological topic rather than day-to-day reality, because in the real world, the UK government and Parliament was already constrained in what kind of actions it could take due to various international agreements and the inter-connectivity of the global economy

https://www.chathamhouse.org/publication/britain-eu-and-sovereignty-myth

http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-eu-referendum-35630757

and here is the icing on the cake :

https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/brexit/2016/03/22/the-sovereignty-myth-leaving-the-eu-may-entail-a-loss-of-sovereignty-for-the-uk/

brexiteers are not only a bunch of maniacal arsonists, they are most importantly ignoramus traitors

Starbuck your argument is shown to be weak when you resort to abuse. It is further weakened by you not answering my points about the 12 chief constables accepting the treason allegations and the censorship of the media who refuse to admit that we still have a constitution. OK it’s not all in one place because it developed over time. When the Americans gained independence they thought it so good that they copied a lot of it and put it in one document..

The reason it was and is so good, was that it is based on the common law which is superior to any statute.What you call the sovereignty of parliament does not exist in law because any parliament can change any law a previous parliament made.

We heard a lot of noise over the last two years about needing a new constitution. That has been kicked into the long grass because those wishing a new constitution realise that the old one would need to be examined. They realised that the old one is better than the ECHR rulings. So they continually try to take away our rights.

The right to get a writ for habeas corpus has been taken away from us. I know because I tried to use it in December last year. Habeas corpus is considered so important that the law states a man can apply to a judge 24/7/365 at no cost . I tried that to be unlawfully rebuffed. So I went to the Royal courts of Justice in the Strand to find that the only office that would contract with me only worked from 10 am to 3.30 pm Monday to Friday. so 24/7/365 unlawfully taken away.

Before a clerk, protected behind a security screen and a security guard, would contract with me I had to pay £850. So that law is broken. Then I was refused access to a judge and had to submit my reasons in writing. Of course he turned me down. However by serving notices on the Judge and the CEO of the Courts and Tribunals Service, I put them in fear of losing their jobs because they acted unlawfully. The judge then telephoned the mental hospital an the lady whistleblower was released.

Starbuck you are either working for the Globalists or you accept what you are told without analysing it. I note that the three links that you provide are all controlled. The British people know something is wrong but they to do not analyse the propaganda put out by the organisations that you admire. The fact that the governments ignore the rule of law, such as unlawfully giving away our sovereignty by signing a treaty subjugating the peoples of this country to the EU is and was treason. So whistleblowers, such as the one I freed, need to be silenced.

Starbuck.

Do you really think your arguments benefit from abuse?

“brexiteers are not only a bunch of maniacal arsonists, they are most importantly ignoramus traitors”

Is your “icing on the cake” the best you can do?

That article attempts to inflate nebulous “influence” to the rank of “sovereignty”.

The former is merely the possibility of changing or rejecting a law – the latter the absolute right to.

Surely any “idiot” can se the difference ? [sorry for that 🙁 ]

The article states the bleeding obvious – that the importing country (the EU) has the right to dictate product standards – as does the UK, the USA and hundreds of other countries (as importers).

Trade Agreements include mutual recognition of standarda where possible.

In case you try arguing that the EU, by being larger dictates product standards – then you would be exaggerating.

Many (if not most) standards get thrashed out at World Trade bodies – over 100 of them.

The UK can regain its seat at these bodies – thus having direct “influence”.

One detail separates the EU from the RoW.

“These standards apply not only to products, but regulation on workers’ rights and health and safety.”

And this is the problem# – EU laws that go beyond cross-border trade

(#NOT workers’ rights but other stuff).

Can you name any other Trade Agreements that delve into a nation’s inner workings ?

Jules, your comments get to why many of the British people are against the present EU. The people know in their hearts something is wrong, but as they have been kept in the dark by all UK governments they can’t formulate the over riding reason why the EU as it is presently constituted is flawed. The UK governments dare not admit that by giving powers to a foreign state, unless we have been defeated in law is against our constitution. To admit that, it would take a man like Trump who on 21 Aug. explained up front that he had changed his mind. The UK is being bogged down in unnecessary negotiations. We should just walk away. The EU would come running because they could not afford to lose our trade.

Only this morning a half truth was discussed on radio 4 today. A divorce lawyer quite correctly stated that our divorce law is common law but this has been subsumed by European law. She must know that you cannot lawfully subsume common law. The supreme court. twice last year, ruled that as common law is superior to statute law the statute that was being argued over, was contrary to common law and therefore was null and void.

The Lisbon treaty is unlawful. The fact that Starbuck gets so angry when an opposite view is aired is because he will not take the time to properly research the subject; or perhaps he agrees and is in the pay of those who steal money from the EU’s budget so much so that no auditor will not sign off the accounts.

“The Lisbon treaty is unlawful. The fact that Starbuck gets so angry when an opposite view is aired is because he will not take the time to properly research the subject; or perhaps he agrees and is in the pay of those who steal money from the EU’s budget so much so that no auditor will not sign off the accounts.”

The accounts have been signed off every year since 2007. What you’ve just repeated here is a myth that gets passed around the internet by people who don’t bother to check their facts and just believe whatever anti-EU tale they hear. It’s quite something that you’ve criticised other people for not taking “the time to properly research the subject” then said something that is completely false and that a five second Google search can show to be wrong.

“In case you try arguing that the EU, by being larger dictates product standards – then you would be exaggerating.”

The EU and the US have been the dominant players in the WTO precisely because they’re extremely large markets.

It’s not difficult to explain why. If you’re an exporter that does a great deal of business in EU countries (or in the US) then you have an incentive to adapt your product to match the regulations within that market. Otherwise you have to manufacture a product for your own domestic market and a completely different product for export, driving up your costs. Therefore the regulations and standards used in large markets de facto spread to other territories regardless of formal attempts at harmonisation. The size of the market dictates how strong that effect is. The EU and the US are two extremely large markets so you find in the harmonisation of standards across the world it’s the European and American models that have often led the way.

This isn’t really a controversial point, it’s a basic principle that almost everyone working in this field is aware of. There’s essentially a silent war being waged between markets over which standards and regulations become global norms and the larger the market is the more likely that standard comes to be used globally. I don’t know many people working in this field (and I know quite a few) who think the claim that the UK “can reclaim its seat at the WTO” amounts to much in practice. In fact I don’t know anyone who thinks the UK is going to diverge substantially on EU standards and regulations for a start. A bit less heat and a bit more light is sorely needed here.

PJ

“you find in the harmonisation of standards across the world it’s the European and American models that have often led the way.”.

A very reasonable statement.

But some very brief research should suggest that “Standards” aren’t quite as simple as “might is right”.

Just occasionally – or perhaps quite often – Standards converge on what actually makes sense.

Just look at the number of Standards Organisations under the Wikipedia article of that title.

Many are national or regional. Many are sectoral.

Moreover, in many (or is it most) cases it is NOT Governments that lead the way on Standards – but industries through their trade bodies.

How many times has it been said that “the law struggles to keep up with technical progress”?

So no doubt the USA or the EU have the power to block an emerging Standard – but much of the time even these “powers” are in the position of merely tweaking what has been settled already.

Which is why it seems better for the UK to be positioned further upstream where the Standards emerge from the spring rather than behind the EU merely implementing what has already been decided.

I’m sure John Major used to talk a lot about “influence” !