There is still no end in sight to the political uncertainty in Catalonia. As Javier García Oliva writes, the issue has raised questions over processes of constitutional reform in Spain. He highlights that constitutional systems tend to make amendments difficult precisely to avoid short-term political winds driving the state in directions which may be damaging to minority interests. But while constitutions should not be carried away by every political tide and current, where there is a tidal wave of opinion, they need to move and accommodate or they risk being swept away.

There is still no end in sight to the political uncertainty in Catalonia. As Javier García Oliva writes, the issue has raised questions over processes of constitutional reform in Spain. He highlights that constitutional systems tend to make amendments difficult precisely to avoid short-term political winds driving the state in directions which may be damaging to minority interests. But while constitutions should not be carried away by every political tide and current, where there is a tidal wave of opinion, they need to move and accommodate or they risk being swept away.

Credit: Fotomovimiento (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

What exactly is happening in Catalonia? The territory is one of the Comunidades Autónomas, a category of Spanish sub-state entities, and amongst all of them, Catalonia already enjoys a higher degree of autonomy and powers than most of its peers. But its political nature and future are being hotly debated. Anybody could be forgiven for struggling to disentangle the twisted strands of the current Catalan saga, which shows no signs of reaching a conclusion any time soon. For those of us in the UK, the problem is exacerbated by a tendency on the part of the Anglophone media to grossly over-simplify, and therefore distort, what is in reality an extremely complicated picture.

There has been a trend towards portraying the political conflict as a David and Goliath struggle between the cultural and linguistic minority who make up the Catalan region, and the mighty central state authorities in Madrid. However, as might be anticipated, this easy narrative is one which will not withstand even the lightest of scrutiny. The real position is indeed far more nuanced, and there are multiple shades of grey. At present, neither the group of pro-independence parties in control of the Catalan Parliament, nor the Government headed by Mariano Rajoy, the President of the Spanish executive in Madrid, are covering themselves with much glory, but the ongoing crisis can still teach the wider world lessons about negotiating constitutional reform, and there are some valuable insights which Britain might gain in contemplating both Brexit and the future of Scotland.

Essentially, pro-independence feelings began to gather in Catalonia after the Spanish Constitutional Court, in 2010, struck down some provisions in the reformed regional constitution, which had been initially approved by the Parliament in Barcelona, and subsequently endorsed by the Spanish legislature. There were calls for a regional referendum on independence, but this faced a fundamental constitutional sticking point. Regional authorities in Spain all derive their legal authority and political legitimacy from the 1978 national Constitution, which was agreed during the period of democratic transition, and as is usually the case in codified constitutions, reform to this overarching framework must be in line with robust and carefully constructed safeguards. As a result, regional authorities cannot arrange referenda on questions relating to the national Constitution, nor unilaterally declare that they are breaking away from the Spanish State. Therefore, the Spanish Constitutional Court twice affirmed this in relation to Catalonia, when regional politicians tried to arrange a vote on the question of independence.

At one level, it is easy to see how this played into the hands of those who wished to argue that Catalonia was being unjustly denied the chance to determine its own destiny. However, looked at more closely, the position is not so straightforward. If the regional authorities were permitted to go ahead and arrange a referendum on their terms and in circumstances outside of the constitutional parameters, what safeguards would be in place? Furthermore, such a trajectory would have implications for the collective consensus on where political sovereignty actually lies within the Spanish State, and so would profoundly affect all Spaniards. Should not they therefore also have a voice?

Moreover, if the result of such a referendum did disclose a majority in favour of change, what would be the position for the minority of citizens within the Comunidad Autónoma who did not wish to be deprived of their rights and status as Spaniards? The pro-independence lobby were keen to portray themselves as an oppressed minority in the national context, but what concern was shown for the rights of a hypothetical minority in the Catalan setting? Obviously, when matters are decided by popular vote, there will often be winners and losers, but constitutions exist, to an extent, precisely in order to safeguard the interests of the losers, and the importance of this should not be underestimated.

To muddy the waters even further, the pro-independence alliance led by Carles Puigdemont unsurprisingly struggled to get the Catalan Parliament to endorse the proposed referendum. In the end enabling legislation was passed, but only after an 11 hour debate during which 52 opposition members walked out of the chamber in protest after what they claimed was an abuse of process and manipulation of deadlines. Faced with politicians ignoring court rulings and acting outside of their political powers, the central Spanish Government did not have any real choice, but to take robust action.

Attempts were made to stop an illegal vote from taking place, and the ballot which went ahead amidst chaos and violence could not realistically disclose anything about popular feeling on the ground. Only those resolutely in support of independence were prepared to participate, and no objective, external scrutiny of the process or result was possible, or even attempted. Nevertheless, Puigdemont claimed the ballot as a mandate for his declaration of independence, which resulted in Spain triggering Article 155 of the Constitution and instigating direct rule from Madrid. Afterwards, fresh elections were held on 21 December 2017, and these gave rise to the political quagmire in which Catalonia is currently stuck.

In short, neither the pro-independence nor the pro-Spain parties within the Catalan Parliament emerged with a working majority, and interestingly, support for the pro-independence options has declined, albeit slightly, since the previous election. After some turmoil, the pro-independence faction managed to gain effective control, because the left-wing and anti-austerity party Podemos refused to vote with the pro-Spanish grouping and claimed to be neutral towards both sides. Interestingly, Podemos’ official position is in favour of a unified Spain, although with the proviso that a lawful referendum should be arranged for Catalonia. However, as the pro-unity parties had coalesced around Ines Arrimadas, from the centre right party Ciudadanos, Podemos were unhappy with the possible implications for social and economic policy.

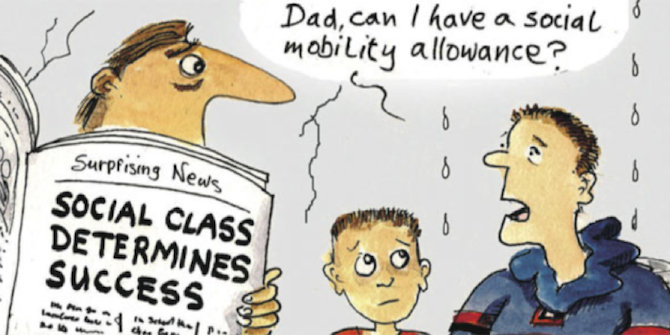

This detail is highly relevant to the kind of democratic mandate which the pro-independence alliance is trying to assert. Significantly, parties in favour of a unified Spain actually represent approximately 52% of the popular vote, but the electoral system favours the pro-independence parties, which have more support in the smaller provinces of Catalonia. Nevertheless, even if we set aside the fact that a majority of the population did not actually vote for pro-independence choices, as things stand, the separatist faction only controls the assembly because Podemos abstained from voting for reasons wholly unrelated to the independence question. This clearly illustrates the point. Codified constitutional systems tend to make constitutional amendments difficult, precisely to avoid the buffeting of short-term political winds and goals driving the state in directions which may be damaging to collective and/or minority interests.

Puigdemont is now in the Belgian capital and unable to return without facing trial. On 30 January, the Speaker of the Catalan Parliament, Roger Torrent, decided to put the vote affirming Puigdemont as the future President of the executive on hold, as this would have been in defiance of a court ruling that he cannot take on the office from abroad. However, the Speaker, backed by Junts per Catalunya and ERC, the two main pro-independence parties, defiantly indicated that no alternative candidate to Puigdemont would be proposed. This was disappointing, as it promised little hope of moving from the present deadlock towards compromise and dialogue. It did not help matters that for some days the lawyers of the Catalan legislature were unable to agree as to whether the two-month window within which a new President must be chosen had been triggered by the declaration of 30 January. The atmosphere of tension and discord was not conducive towards a softening of the rigid political stances taken, and when the legal report eventually materialised, it confirmed that because a vote had not taken place, time had not in fact started to run.

Despite the assertion that no second-choice President would be put forward in place of Puigdemont, behind the scenes in the pro-independence camp, political horse-trading is clearly taking place. The two main pro-independence political parties are known to be actively negotiating over an alternative, with the face-saving gesture of making Puigdemont “honorary President”, alongside the person invested with legal and political power, and it is to be hoped that there will soon be some tangible progress towards a workable and lawful solution, whatever that might finally be. Needless to say, in any democratic context, a plurality of views on political questions should be expected and welcomed, but whatever stance is taken on the independence question, this seemingly never-ending chaos is lamentable. Residents of Catalonia, and indeed the rest of Spain are starting to despair.

All things considered, it must be seriously questioned whether the long term, fundamental rights of citizens, and the destiny of this Comunidad Autónoma, should be decided by the political actors in the centre of this melee. Constitutions exist in order to govern the collective life of states, as well as the rules of legal and political engagement. Undoubtedly, amendments and progress will be necessary at times, but this should be done in accordance with a recognised, coherent process and in a controlled manner.

In many contexts, a bare majority is insufficient for constitutional change, and an alteration to the status quo requires an agreement of two thirds of the electorate. Such stringent requirements are not there to shackle, but to protect our citizens. The fact is that once stripped away, rights cannot always be easily regained, and where opinion is balanced on a knife-edge, and may easily alter in weeks or months, irrevocable decisions are usually best avoided. Constitutions effectively have the equivalent of the query which computers often raise, including that warning sound and message box beginning with the well-known ‘Are you sure you want to…’

In light of this, the desire of pro-independence politicians in Catalonia to dismantle constitutional protections to further their own political ends cannot be praised, or even justified, and those with political power must defer to the courts and the rule of law if a liberal democracy is to function as such. Equally, it is unquestionable that this can only work if legitimate and functional channels are found to discuss and debate constitutional reform, and where necessary, move it forward.

In stonewalling any discussion on independence, Rajoy closed off collaborative avenues, and unwittingly prompted Catalan politicians to step away from constitutional dialogue. In assessing our own legal and political future, we might wish to consider how we can put safeguards in place, but also how we can prevent those safeguards becoming damaging constraints. Constitutions should not be carried away by every political tide and current, but where there is a tidal wave of opinion, they need to move and accommodate in preference to remaining immobile and being swept away.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Javier García Oliva – University of Manchester

Javier García Oliva – University of Manchester

Javier García Oliva is a Senior Lecturer in Law at the University of Manchester.

Catalonia has been awaiting “legitimate and functional channels to discuss, debate and move forward constitutional reform” for eight years now .

Too bad. The Spanish State must ensure its constitutional framework.is in harmony with the international treaties it has signed proclaiming the right of peoples to self-determination (Art 1.2 of the UN Charter):

Polls suggest that the Catalan people favour “more Catalonia” and the last regional elections reconfirmed that 48% favour outright independence. That does not mean that the remaining 52% reject a sovereign Catalan State as you seem to suggest. Many of them simply reject the trauma of unilateral action and prefer a softer approach towards State building, in contrast with the hard-liners or left-leaning radicals.

It is only 24% (PP and Cs) that voted for the status quo / recentralization of powers. Hhistorically, it is more like 15% and will likely fall back to those levels once the storm settles). .

The Catalan people are basically stuck in a rut, unable to move forward towards the higher degree of autonomy and powers they seek. This is no tide or fad, it is the sustained wish of the Catalan people ever since they started voting in regional elections in 1932.

Could you not spare a word for the poor political prisoners, as Amnesty calls them, locked up in a Spanish dungeon for well over 100 days now???

Nor a word of protest for Rajoy’s shocking use of pre-meditated violence on the 1 October elections?

This piece accurately reflects the concerns of Spanish nationalism.

The Canadian supreme court offers a better way forward than the Spanish constitution, negotiated under the shadow of Franco. The settled will of a federal entity to become independent should be respected, regardless of whether it is Scotland, Quebec or Catalonia. The constitution is there to enable this, not block it.

The Spanish nationalists haven’t shaken off their post-Franco nationalism. You see it in their attitude not just to Catalan but also Gibraltarians, Kosovars and Falkland Islanders. It’s time they were called out on this but all who believe in democracy.

A note of caution to King Felipe is Lame: hard line catalan nationalists like Junqueras,or los dos Jordis are in jail because, alongside Puigdemont and Forcadell, they committed the gravest crimes of rebellion, secession and grand theft of public monies against the Spanish state and the people of Catalonia since Tejero, Armada and Milans led the ‘golpe’ in 1981 in the 23F. The fact that Rajoy and Soraya Saenz refuse to arrest, investigate and punish all those involved in the massive ‘trama golpista’ in Catalonia (such as Pablo Iglesias, Jaume Roures, Ada Colau, the 2300 public servants who willingly run a ‘golpista’ TV3 networketc) is not an excuse for not using the law to its maximum effect as a means of dissuading future political adventurism. As Juan Carlos Girauta, spokesman for Cuidadanos said on Cadena Ser a few months ago, ‘No queremos pactar con los golpistas…no pacto con los que quieren hacerme extranjero’. (OK diario 20/9/2017)

Why not do one or both of these? a. re-approve the Cortes’ decision to extend more rights to Catalonia and or b. make Spain a Federal State?

Why not restore the language primacy and more financial controls per the Cortes’ 2006 decision and or make Spain a Federal State where the regions determined the Constitution rather than a top-down from the center State with regional autonomies?