There is a divide between how Remainers and Leavers perceive the UK’s economic performance and other policy developments, explain Miriam Sorace and Sara B. Hobolt. A major consequence of this lack of agreement about basic facts is that reaching a consensus on how to navigate Brexit becomes even more complicated.

There is a divide between how Remainers and Leavers perceive the UK’s economic performance and other policy developments, explain Miriam Sorace and Sara B. Hobolt. A major consequence of this lack of agreement about basic facts is that reaching a consensus on how to navigate Brexit becomes even more complicated.

On the 23 June 2016, UK citizens voted to leave the European Union. The vote came after a heated referendum campaign where the Remain camp highlighted the economic dangers of Brexit and the Leave camp promised to bring back control of borders and reduce immigration. The outcome of the referendum has subsequently triggered strong political identifications along Brexit lines.

Is this new fault-line in British politics also shaping beliefs and perceptions, in line with Brexit campaign promises? We know that group identities, such as party identification, tend to shape how people select and interpret new information, sometimes leading to ‘cognitive illusions’. Our study finds that the new Brexit identities have indeed resulted in distorted (or ‘biased’) images of the key issues of the economy and immigration levels.

To examine how Brexit has shaped such views, we use data from the British Election Study (BES) 2014-2017 panel. This allows us to compare assessments of the economy and immigration by Leavers and Remainers before and after the Brexit vote. To the extent that the referendum has led to very different evaluations of the economic performance and of immigration levels among the two groups, then this is evidence that the referendum vote may have distorted perceptions.

It is worth noting that data from the Office of National Statistics shows minimal changes in key indicators of UK growth and immigration rates in the 2016-2017 period. Hence, if perceptions were not biased by the referendum vote, we wouldn’t anticipate substantial changes in people’s views. However, if the emerging Brexit identities play a role, we expect people to view changes in the economy and in immigration in ways that confirm their referendum vote: Remainers should become more pessimistic about the economy after the vote, while Leavers should become more optimistic about immigration (i.e. observe lower immigration levels).

To see if that is the case, we measure economic and immigration perceptions are using the following survey items of the BES:

- Do you think that the economy is getting better, getting worse or staying about the same?

- Do you think that the level of immigration is getting higher, getting lower or staying about the same?

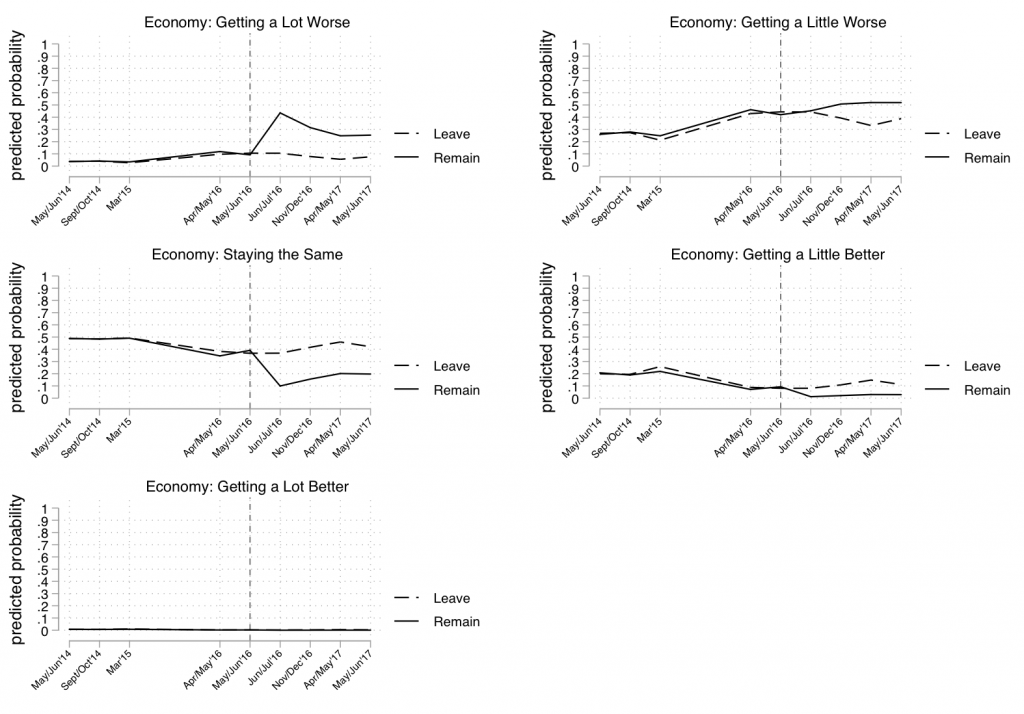

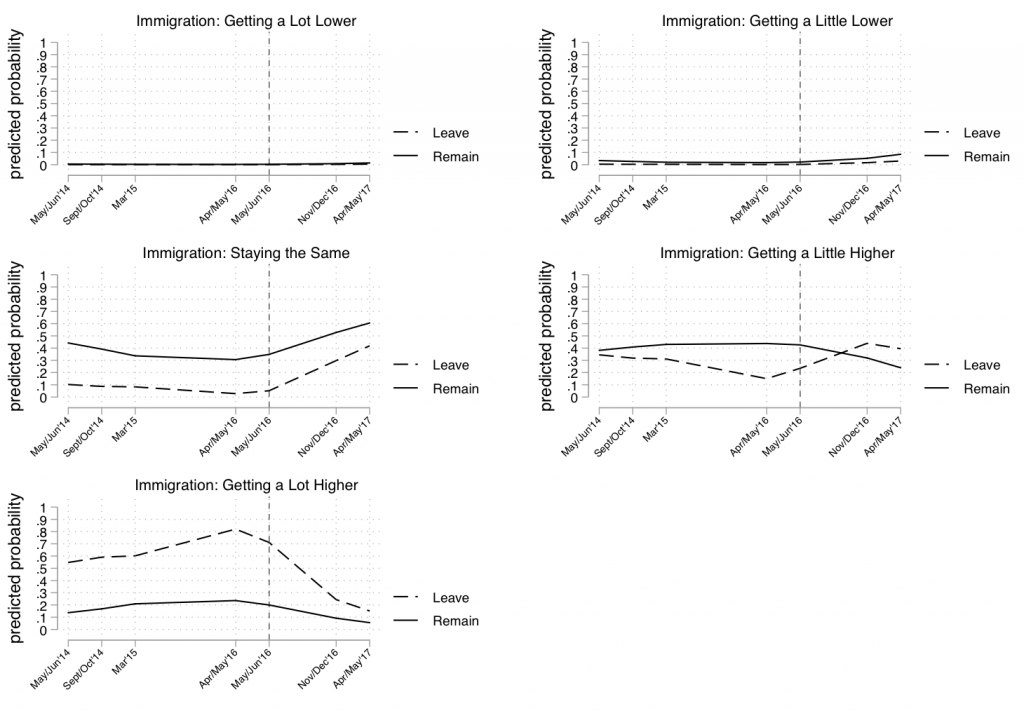

Figures 1 and 2 below represent graphically the results (based on ordered logit panel regression models).

Figure 1: Economic perceptions

Note: Predicted Probability Graphs for outcomes 0-1 (economy got worse); 2 (economy stayed the same) and 3-4 (economy got better). Covariate profile held constant at modal categories: Labour, 46-55 age bracket, A-level educational attainment, female, income: 20-25k. All other variables held at their mean. Source: BES

Note: Predicted Probability Graphs for outcomes 0-1 (economy got worse); 2 (economy stayed the same) and 3-4 (economy got better). Covariate profile held constant at modal categories: Labour, 46-55 age bracket, A-level educational attainment, female, income: 20-25k. All other variables held at their mean. Source: BES

Figure 2: Perceptions of immigration levels

Note: Predicted Probability Graphs for outcomes 0-1 (decreased levels of immigration); 2 (same levels) and 3-4 (increased levels of immigration). Covariate profile held constant at modal categories: Labour, 46-55 age bracket, A-level educational attainment, female, income: 20-25k. All other variables held at their mean. Source: BES.

Note: Predicted Probability Graphs for outcomes 0-1 (decreased levels of immigration); 2 (same levels) and 3-4 (increased levels of immigration). Covariate profile held constant at modal categories: Labour, 46-55 age bracket, A-level educational attainment, female, income: 20-25k. All other variables held at their mean. Source: BES.

The figures clearly demonstrate changes in economic and immigration perceptions (by Remain voters and Leave voters, respectively) immediately after the referendum. Remainers became noticeably more pessimistic about the economy after the vote, while Leavers perceive immigration rates as lower, in line with the respective campaign promises. We can see very clear differences before and after the Brexit vote in perceptions of the main campaign issues, the economy and immigration – holding constant partisanship, gender, age, education and income. This is despite the fact that the UK had yet to leave the EU, and actual changes were limited.

What about differences in the perceptions of Leavers and Remainers? Have they converged or diverged in the aftermath of the vote? In the case of economic performance evaluations, Leavers and Remainers shared very similar assessments before the referendum, but started diverging immediately after the vote. There is a clear contrast when it comes to the immigration issue: the two camps held starkly different perceptions of immigration rates before the referendum, but they started converging afterwards, with Leavers approaching Remainers’ evaluations.

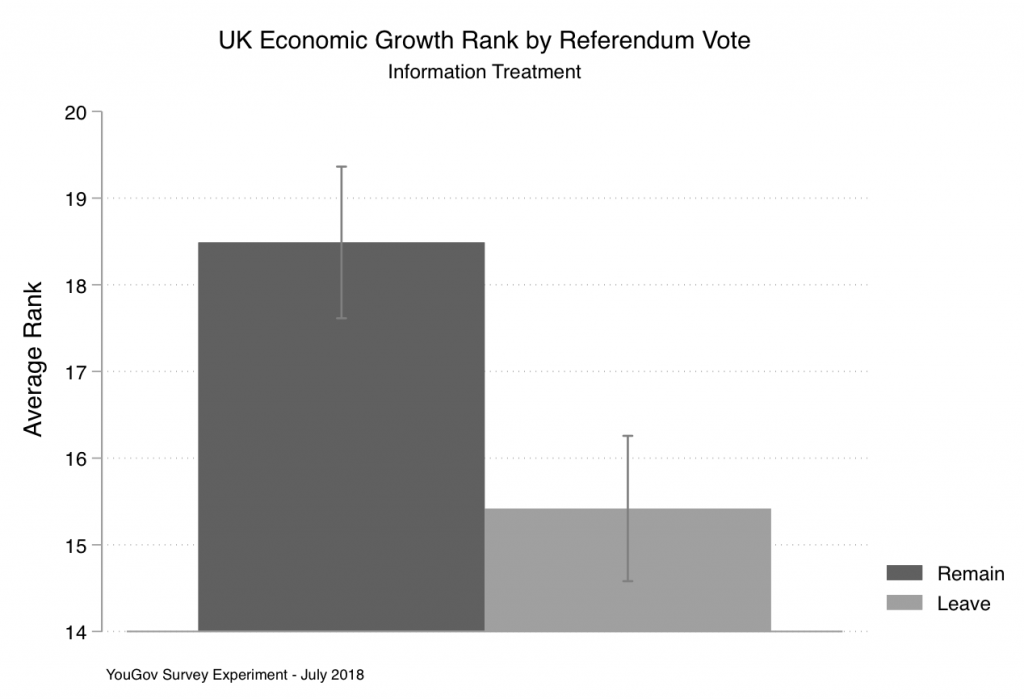

In addition to this panel regression analysis, we also ran a survey experiment run in July 2018 to examine how Remainers and Leavers respond to economic facts. The experimental results confirm the patterns above and further reveal that these biases are not simply due to Leavers and Remainers receiving different types of information; instead, we find that they interpret the same new information in radically different ways.

Figure 3 shows how UK economic growth was ranked in comparison with other developed economies by Leavers and Remainers after respondents were given information about growth rates. The results clearly demonstrate that even when provided with information on UK growth from the Office of National Statistics, Leavers and Remainers still rank the performance of UK growth vis-à-vis the other 34 OECD economies significantly differently. Leavers rank the UK economy more optimistically (placing the UK 15th out of 34) than Remainers (placing the UK 18th out of 34). These differences are even greater when we remind (‘prime’) individuals about the Brexit referendum.

Figure 3: Economic perceptions – survey experiment

Note: Answer to the survey question “How do you think the UK’s economic growth rate currently ranks in comparison to other the 34 developed countries part of the OECD? Please give a ranking from 1 to 34, where 1 means that you consider the UK to currently be the best performing economy in the developed world, while 34 means that the UK is the worst performing one. If you don’t know the answer, please make your best guess”. Source: Hobolt & Sorace – YouGov, July 2018.

Note: Answer to the survey question “How do you think the UK’s economic growth rate currently ranks in comparison to other the 34 developed countries part of the OECD? Please give a ranking from 1 to 34, where 1 means that you consider the UK to currently be the best performing economy in the developed world, while 34 means that the UK is the worst performing one. If you don’t know the answer, please make your best guess”. Source: Hobolt & Sorace – YouGov, July 2018.

Our study highlights that in the aftermath of the referendum, citizens view economic and immigration politics through new Brexit-tinted glasses. Leavers and Remainers immediately responded to the referendum result by updating their opinions in line with the respective referendum campaign promises and beliefs. Similar to party identity, the Brexit referendum has thus biased people’s view of key political issues.

This divide between Remainers and Leavers in their economic perceptions is likely to make any attempt to foster national unity around an eventual Brexit negotiation outcome more difficult, as Remainers will focus on the negative economic consequences, while Leavers will see the developments in a very different, and more positive, light. When there is no agreement about the basic facts of economic and policy developments, it becomes far more difficult to find a consensus about appropriate policy solutions. It also complicates matters for those who advocate a second referendum on the basis of “what we now know to be the consequences of Brexit”. Given the divergence in views, a second referendum would likely lead to another clash between ‘project fear’ and ‘project hope’ strategies, potentially deepening the divide.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article originally appeared at our sister site, British Politics and Policy. It gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain)

_________________________________

Miriam Sorace – LSE

Miriam Sorace – LSE

Miriam Sorace is LSE Fellow in EU Politics, having joined the European Institute in September 2017. She earned her PhD in Political Science in April 2017 from Trinity College, Dublin.

–

Sara B. Hobolt – LSE

Sara B. Hobolt – LSE

Sara B. Hobolt is the Sutherland Chair in European Institutions at the European Institute and the Department of Government at the LSE. She is also an Associate Member of Nuffield College, University of Oxford, and a Fellow of the British Academy.

If the UK population is divided, and members of both parties are divided, will the country face civil unrest after Brexit?

The nation is divided. But it seems the authors would prefer us to walk towards the Brexit cliff, rather than try and resolve it by asking the people to vote on three options that are on the table: Hard-Brexit, Soft-Brexit, or Remain.

I can’t see rioting in the streets but I do see an increasingly divided society along similar lines to the present USA.

Unless the UK economy not only recovers from any post Brexit downturn ( I do see at least a mini recession post Brexit) but preforms remarkedly well, the divide is set to continue for more than a generation.

Well, you have all been proved wrong since