In Israel, Jewish conversions by first and second generation repatriates from the former Soviet Union are often depicted in public discourse as ‘wink-wink’ conversions, whereby converts and the state pretend that converts’ commitment to the Jewish faith and practice is sincere rather than performed solely for the duration of the conversion process. In When the State Winks, Michal Kravel-Tovi unsettles this narrative, offering a rich and insightful ethnography that invites readers to think in novel ways not only about the relationship between conversion and the State of Israel, but also about day-to-day encounters between the state and its citizens, writes Yulia Egorova.

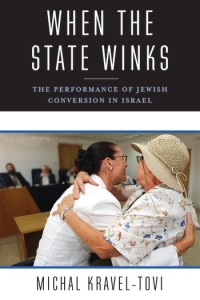

When the State Winks: The Performance of Jewish Conversion in Israel. Michal Kravel-Tovi. Columbia University Press. 2017.

Religious conversion plays a very special role in the political landscape of the State of Israel. One can become an Israeli citizen through conversion to Judaism and one can formalise one’s status as a Jewish person through conversion without which achieving changes in personal status can be difficult, if not impossible.

Michal Kravel-Tovi’s award-winning monograph, When the State Winks: The Performance of Jewish Conversion in Israel, is a ground-breaking study of the state-sponsored conversion process, focusing mainly on the conversion of the first and second generation repatriates from the former Soviet Union who either fail to qualify as halakhically Jewish or struggle to provide evidence of this particular modality of being Jewish that would be acceptable for the rabbinic authorities of the state. Such conversions are often depicted in Israeli public discourse as ‘wink-wink’ conversions, where both the converts and the state agree to pretend that the converts’ commitment to the Jewish faith and practice is sincere rather than performed merely for the duration of the conversion process and abandoned as soon as the conversion is formally completed.

Kravel-Tovi’s rich and insightful ethnography unsettles this narrative and invites the reader to think in novel ways not only about the relationship between conversion to Judaism and the State of Israel, but also more broadly about day-to-day encounters between the state and its citizens. Her study is based on long-term fieldwork conducted among conversion candidates and conversion actors in schools (where candidates are instructed in Jewish practice), rabbinic courts (where judges decide on the candidates’ applications) and ritual bathhouses (where successful applicants finish the conversion process). When the State Winks explores how different actors negotiate the challenges generated by the contradictions between Israel’s national goal of addressing the perceived demographic crisis brought by the arrival of a substantial number of non-Jewish repatriates from the former Soviet Union and the halakhic understanding of conversion as a sincere commitment to a particular modality of religious observance.

Image Credit: (Pixabay CC0)

Image Credit: (Pixabay CC0)

The book is divided into two thematic sections. The first discusses the political life of religious conversion in the State of Israel and the relationship between conversion and religious Zionism. The second half documents different dimensions of the interactions between the applicants and the state in conversion schools, rabbinical courts and ritual bathhouses, painstakingly unravelling the dramaturgical encounters between the two sides throughout the conversion process. The book concludes with an epilogue which consolidates its central theoretical argument about ‘winking relations’, calling attention to the interactional and interdependent nature of alliances involved in the production of both state power and state subjects.

Kravel-Tovi insightfully points out that the conversion process is a complex experience that cannot be reduced to a binary opposition between pretense and sincerity, and that as anthropologists we should not presume that we can always distinguish between ‘truths’ and ‘lies’ in the social realities we investigate. These are important starting points, but the author’s argument goes much further. Kravel-Tovi develops the concept of ‘winking relations’ to help us understand how in the context of multiple contradictory conditions of Israeli politics – where tensions arise between population policies and individual modes of self-identification, between national goals and religious laws, between the rabbinic establishment and secular Israeli citizens – the Orthodox representatives of the Israeli nation-state and the conversion candidates from the former Soviet Union manage to achieve their shared goal of undergoing and facilitating conversion.

As the author puts it, ‘by winking, individuals can create a shared understanding and invite each other to collaborate in the production of refined meaning’ (18). In her analysis, Kravel-Tovi underscores the collaborative nature of winking relations, arguing that what transpires in the everyday interactions between conversion candidates and the religious agents of the state is a sophisticated system of messages regarding the requirements placed on the applicants and the importance that conversion holds for the state. The book shows that in the conversion encounter the stakes are so high for both sides that each party becomes entangled in a relationship of mutual dependency.

On a broader theoretical plane, the book brings a dramaturgical perspective on the state, emphasising the enormous amount of effort that both sides put into managing their institutionalised encounters and highlighting ‘how political power is enacted by placing the burden of performance on real people working and constituting their identities within state institutions’ (36). Kravel-Tovi shows how both the agents of conversion and conversion candidates ‘wink’ at each other throughout the process. For instance, the book describes how conversion teachers both denounce insincere applicants and teach their students how to manage their performance of religious practice better in order to pass the conversion test. These practices make it clear that as much as the candidates from the former Soviet Union need the state to allow them to convert in order to be considered halakhically Jewish, the state just as much needs them to succeed in their conversion in order to maintain its status of a Jewish state. The agents of the state therefore have to be able to limit their suspicion and to overlook what some would see as signs of ‘pretend’ rather than ‘sincere’ religious practice.

When the State Winks is written in an engaging style that will instantly draw in both a specialist and a non-specialist reader. It can be recommended to a wide range of academic audiences and is a must-read in anthropology of religion at the intersection with political anthropology and anthropology of the state.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article is provided by our sister site, LSE Review of Books. It gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Yulia Egorova – Durham University

Yulia Egorova is Professor of Anthropology at Durham University. She is the author of Jews and Muslims in South Asia: Reflection on Difference, Religion and Race (OUP, 2018).

Find this book:

Find this book: