This discussion focuses on the issue of participation in relation to fieldwork in China. Drawing upon more than 24 months of musical ethnographic fieldwork in rural Kam (in Chinese, Dong 侗) minority areas of southwestern China since 2004, I describe the main participatory aspects of my research methodology. I look at three of the main challenges—linguistic barriers, cultural concerns and research positionality—that I faced while utilizing participation as part of my research, and describe some of the most effective ways in which I was able to turn these possible “constraints” into productive ends, writes Catherine Ingram.

During the past nine years I have undertaken more than 24 months of ethnographic research in rural Kam (in Chinese, Dong 侗) minority areas of southwestern China to investigate Kam music. Through being invited to participate in daily activities and musical events in rural Kam communities, and through my involvement in the lives of Kam friends and teachers, I have learnt to speak the Kam language and sing many Kam songs (singing is the main musical activity in Kam communities). The range of activities I have participated in together with Kam friends has extended from preparing food, collecting wild foods in the mountains, and planting and harvesting rice to learning Kam songs, watching and discussing VCD and DVD recordings of Kam singing performances, and singing various genres of Kam songs at weddings, at New Year celebrations and in many staged performances. A documentary (click here) about my research that was produced by Guizhou Television in 2011 (based on an earlier documentary made by the same director in 2006) gives an overview of some of the many different ways in which I participated in Kam community and musical life.

Participation has allowed me experiences and understandings that have been extremely beneficial for my research, and has also been the key to developing relationships with Kam people and defining my position in Kam communities. It has helped to make my ongoing research a more collaborative undertaking, and has better ensured that some of my research activities have direct benefits for Kam communities. While my use of a participatory research methodology has also had advantages—and challenges—for the members of Kam communities where I have conducted research, here is not the forum for discussing either of those aspects (part of my decision to undertake research in this manner was made on the basis of projecting the likely benefits and challenges). Instead, following a brief background about Kam people and Kam music, I discuss three of the main challenges that I faced in utilising participation as part of my research—challenges related to linguistic barriers, cultural concerns, and research positionality. I also describe some of the most effective ways in which I was able to turn these possible “constraints” into productive ends.

Kam people and Kam music

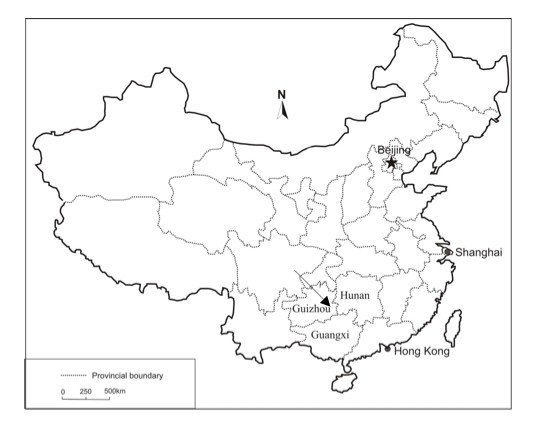

Kam people, with a population of more than 3 million, are one of China’s fifty-five officially recognised minority groups. Although most Kam people live in southeastern Guizhou province and the bordering areas of adjacent Guangxi and Hunan, the majority of Kam youth (and many middle-aged villagers) now spend significant periods—often years—working or studying outside their home villages. Most of my research was undertaken in Sheeam (in Chinese, Sanlong 三龙), a Kam region in Liping county, southeastern Guizhou, which is well known for its many singing traditions.

Kam people in Sheeam and many other Kam areas speak a dialect of Kam as their first language. The Kam language is a tonal Tai-Kadai family language that does not have a widely used written form, and is quite different from the various dialects of Chinese. It is the main language used in singing the many different genres of Kam songs, including “big song” (sometimes also referred to as “grand song”), the Kam song genre that was inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2009 (click here, here and here to visit the UNESCO website that feature big songs).

Challenges in utilising participation in research

One of the main challenges I faced throughout the research concerned linguistic barriers. I began my research with good fluency in Mandarin and some understanding of one Chinese dialect used in Hunan, but I had no experience with Kam or the local Chinese dialect spoken in Liping county. Consequently, I found it most useful to approach Mandarin speakers in Kam villages for help with learning Kam. In most cases, the best Mandarin speakers were secondary school students. With patience and a lot of time, with regular Kam song learning and discussion, and with daily involvement in many different activities where I was surrounded by people speaking Kam, I was gradually able to gain fluency in the language.

My new Kam friends also quickly gained confidence in sharing jokes about the many hilarious things I said and did while learning to speak Kam, and these humorous aspects of my language learning were often a favourite topic of discussion. But the jokes were helpful for reinforcing my language learning and, especially, seemed to make it more enjoyable for Kam people to engage with a novice Kam speaker. I quickly learnt that my attempt to learn the language was also valued by many villagers as demonstrating respect for local culture. In fact, on many occasions when my language skills were less advanced, I found that people with little Chinese ability were willing to use their limited Chinese to communicate with me once I had first made an attempt to talk with them in Kam.

Cultural concerns were another challenge in conducting this research, as I needed to learn the Kam norms of social and musical participation. Many ethnomusicologists have also recognised this kind of concerns. As John Miller Chernoff describes it:

As his [sic] perception of the configuration of events changes, a researcher realizes that the process of learning about and adapting to life in foreign cultures is as much a breaking down of the categories and concepts he has brought with him as it is a recognition and realization of the most meaningful perspectives he can establish (Chernoff 1979: 20)

Certain Kam social conventions differed from those I had encountered in other parts of China or elsewhere, and I had to be taught many aspects just as children were instructed and socialized within Kam society. I was extremely fortunate in always being able to rely on guidance and support from my three singing teachers in the village and from Nay Lyang-jyao, one of my closest Kam friends (and whose family I lived with in Jai Lao, the largest village in Sheeam). Nay Lyang-jyao would sometimes offer suggestions about how I should act (or should have acted) in a particular situation, and I could ask her questions about how I should deal with particular issues. Other members of Nay Lyang-jyao’s family also often offered advice and guidance, as I began to be seen as part of their family and thus my actions reflected upon them to some small degree. This advice ranged from instructions about particular statements I should make at certain social junctures to the gifts I should offer at weddings or the way I should modestly refuse at least the first few requests to sing a Kam song. This input was critical to the success of my participation in Kam society and to my development of some depth of understanding of Kam culture. It also helped others in the community accept my involvement in their lives far more easily.

Finally, positioning myself in the research context and developing relationships with people presented various kinds of challenges. I had to develop ways to make my intentions and motivation understood, to convey the respect I held for my friends and their culture, and to build rapport across cultural and linguistic divides. Conveying this respect through being willing to engage in the muddy, exhausting or mundane tasks that are central to village life, learning to speak Kam, and participating in and evidently appreciating Kam culture (as illustrated through some of the footage in the Guizhou Television documentaries) was crucial to the relationships I have developed with Kam villagers and to my research positionality. Keith Ridler also notes the connection between shared tasks, friendship and ethnographic research, stating that:

What is central is that friendship is engendered by the sharing of practical and mundane activity… Such relationships are at the heart of the ethnographic encounter as it is experienced in fieldwork… (Ridler 1996: 255)

Many of the Kam people I work with have already had extensive experience of being misquoted, misunderstood, required to explain themselves in a second language, and having their words or cultural practices appropriated by others who do not attempt to learn their language or appreciate their culture and knowledge. As Anthony Seeger points out:

Colonized peoples and other so-called subaltern populations live in an environment in which others insist on telling them what to do, rarely take the time to understand what they are already doing, and show little respect for their way of life. It is very easy for researchers to reproduce that pattern even while professing to respect the local traditions (Seeger 2008: 279)

Many Kam friends were willing to go to great lengths to support and become involved in my research, to teach me about Kam culture, and to assist with checking or elaborating upon information about Kam people and music. This seems to suggest that Kam villagers saw my research approach as being appreciative of Kam culture and lifestyle, and that through the research process my friends felt understood and respected.

Final remarks

This brief discussion of three of the main challenges I encountered in utilising participation in musical ethnographic research indicates that employing such a research methodology requires consideration of many complex and interwoven factors. However, I hesitate to suggest that these challenges are necessarily “constraints.” As I have shown, it is certainly possible to overcome these and other difficulties in participatory research. Moreover, the process or result of overcoming these factors often leads to insights or actions that can be instrumental in the success of the research project. For instance, the challenge of learning to speak Kam was a process that also built positive relationships; the challenge of learning from my friends about Kam cultural norms helped me to gain a great deal of knowledge about Kam culture and language; and the challenge of positioning myself within Kam communities led to me joining with my friends and teachers in many different kinds of daily village activities, enabling the kinds of invaluable insights into Kam music-making that could only arise through direct experience and through positive, equitable and long-lasting relationships.

References

Chernoff, J.M. (1979) African Rhythm and African Sensibility. Aesthetics and Social Action in African Musical Idioms. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press

Ridler, K. (1996) If Not the Words: Shared Practical Activity and Friendship in Fieldwork. In Jackson, M. (ed.) Things as They Are: New Directions in Phenomenological Anthropology. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, pp. 238–258

Seeger, A. (2008) Theories Forged in the Crucible of Action: The Joys, Dangers and Potentials of Advocacy and Fieldwork. In Barz, G.F. and Cooley, T.J. (eds.) Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology. New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 271–288

About the author

Catherine Ingram a Newton International Fellow in the Department of Music, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, and an Honorary Fellow at the University of Melbourne, Australia. She was previously an Endeavour Australia Cheung Kong Research Fellow (Australia/China, 2010–2011) and a Postdoctoral Fellow at the International Institute of Asian Studies (The Netherlands, 2011).

A Note on the Research and Results

My research within Kam communities has been ongoing since 2004, and has mainly involved communities in the Sheeam region (in Chinese, Sanlong 三龙), in Liping county, southeast Guizhou province. It has led to a number of single and co-authored publications in areas including not only Kam minority music but also its relationship to discourses concerning gender, the environment, research ethics, digital fieldwork, anthropological studies of ‘tradition’ and notions of intangible cultural heritage. The fieldwork and research have led to a number of publications, some of which are listed below:

- McLaren, A., English, A., He, X. and Ingram, C. (2013) Culture, Heritage, Eco-sites and the State in Contemporary China. Champaign, IL: Common Ground Publishing

- Ingram, C. (2013) Understanding Musical Participation: ‘Listening’ Participants and Big Song Singers in Kam villages, Southwestern China. In Russell, I. and Ingram, C. (eds.) Taking Part in Music: Case Studies in Ethnomusicology. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, in association with the European Seminar in Ethnomusicology, pp. 53-68

- Ingram, C. (2012) Ee, mang gay dor ga ey (Hey, why don’t you sing)? Imagining the Future for Kam Big Song. In Howard, K. (ed.) Music as Intangible Cultural Heritage: Policy, Ideology and Practice in the Preservation of East Asian Traditions. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, pp. 55-75

- Ingram, C. (2012) Researching Kam Minority Music in China. In Ng, N. (ed.) Encounters : musical meetings between China and Australia. Toowong, QLD: Australian Academic Press, pp. 63-80

- Ingram, C. (2012) Tradition and Divergence in Southwestern China: Kam Big Song Singing in the Village and on Stage. The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 13 (5): 434-453

- Ingram, C. (2011) Echoing the Environment in Kam Big Song. Asian Studies Review 35(4): 439-455

- Ingram, C. with Kam song experts and singers Wu Jialing, Wu Meifang, Wu Meixiang, Wu Pinxian, and Wu Xuegui (2011) Taking the Stage: Rural Kam Women and Contemporary Kam ‘Cultural Development’. In Jacka, T. and Sargeson, S. (eds.) Women, Gender and Rural Development in China. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 71‐93

Other writings related to this research include:

- “The Multiple Meanings of Tradition: Kam Singing in Southwestern China,” Newsletter for the International Institute of Asian Studies (No. 60, Summer, 2012), pp. 4‐5

- “Kam ‘Big Song’ Down Under,” New Mandala (April 2012)

- “China’s 60th Anniversary From the Margins,” New Mandala (October 2009)

Two documentaries produced about this research:

- Ga Lao My Love 嘎老 My Love [Big Song, My Love]. 2006. Dir. Bai Chuan. Guiyang: Guizhou Television

- Ai chang Dongge de Kaiselin 爱唱侗歌的凯瑟琳 [Catherine, Who Loves to Sing Kam Songs]. 2011. Dir. Bai Chuan. Guiyang: Guizhou Television

About Kam people, James R. Chamberlain (2016) proposes that their ancestors originated in the state of Chu and only moved slightly southwards to their present-day area from their orignal homeland.