This contribution reflects upon the author’s earlier exposure to public media and its positive implication on her own fieldwork, encouraging other researchers to consider the potential benefits of being known in the (non-academic) ‘field’. Against the common perception of researchers being ‘quiet observers’ in the field, media exposure brought about familiarity and trust that seemed extremely valuable to the research in Zambia, writes Alice Evans.

Oh there’s no need for that’, exclaimed the Maternal and Child Health Co-ordinator as she dismissed my formal letter of introduction from the permanent secretary. ‘I already know who you are, Mapalo!

This was surprising since we had never met, nor had I ever before been to the rural Zambian district in which she worked. Yet Beatrice seemed remarkably at ease and familiar with me, immediately inviting me to stay at her house while I undertook my research.

This experience was not uncommon. Whether I was wedged in a bus traversing pot-holed roads in Kalulushi, hailing a unmarked taxi in Kitwe, queuing at Shoprite (a South African supermarket chain) in Luanshya (90 km west) or passing provincial ministers in Lusaka (388 km south), I was often recognised. A broad range of people knew my name (or at least the Zambian one I had been given), the subject of my research and my fluency in Bemba.

This status proved remarkably significant. Some participants felt they already knew me, as well as my agenda. This enabled trust and rapport, both of which are critical to any ethnographic project yet usually require a great deal of time to develop. Besides improving the quality of my empirical investigation, being known and happily greeted by strangers also enhanced my own well-being – which was equally critical to the research process.

So how on earth did I become known? Television. At the beginning of my research on maternal health, I was interviewed on a Bemba language state television programme, airing on Sunday lunchtime. Programmers at the Zambia National Broadcasting Cooperation invited me to return on two further occasions, the third being Kwacha Good Morning Zambia! – the weekend equivalent of BBC Breakfast. At the time of filming I did not know quite how important these interviews would be.

Another unexpected consequence was participants’ expressed joy in seeing their narratives represented on television. I appeared to gain legitimacy through demonstrating how I intended to communicate my findings, their stories. This kind of accountability seemed much more important to them than the rather conventional draft summaries of my findings that I had previously circulated for their feedback.

I write this account to encourage other researchers to consider the potential benefits of being known in the (non-academic) ‘field’. Of course there may also be negative consequences. Publicly stating one’s own view likely influences how one is perceived by participants, possibly shaping their narratives and behaviour. Keen to avoid this hazard, I intentionally limited my responses when interviewed before undertaking my research. I spoke about the major causes of maternal mortality, not my specific inquiry into the causes of increasing attention to maternal health care at district and central government levels in Zambia. The intention here was to convey my interest and knowledge on the broad topic, rather than my research hypotheses. I did discuss my findings in subsequent television interviews, but these were broadcast only after I had conducted the major part of my research. In this later period, I was purposefully seeking critique of my data and analysis – inviting key institutional personnel to read draft summaries.

Television exposure is not the only way of being widely known in a locality. Another (perhaps more common) avenue is to just greet strangers – as I did in an earlier research project on the causes of growing support for gender equality in Zambia. When walking through urban Kitwe’s vast market (one of the largest in Zambia), one female participant who had traded there for eighteen years encouraged me to greet every single trader we passed, regardless of whether I was interested in interviewing them. I had not done this originally since I had not assumed that others would want to greet me; doing so felt rather presumptuous. Moreover, it was extremely time-consuming to take the time to speak to everyone, on each route through the market. But I followed her advice – to appear open and friendly – and thus became widely known. Many called me her child – ‘umwana wa BanaMayuka’ – just as she did.

Just as with television exposure, concerns might be raised about being too well-known and drawing attention to oneself, rather than quietly observing naturally-occurring phenomena. In my own experience, however, familiarity and trust seemed extremely valuable to the research process.

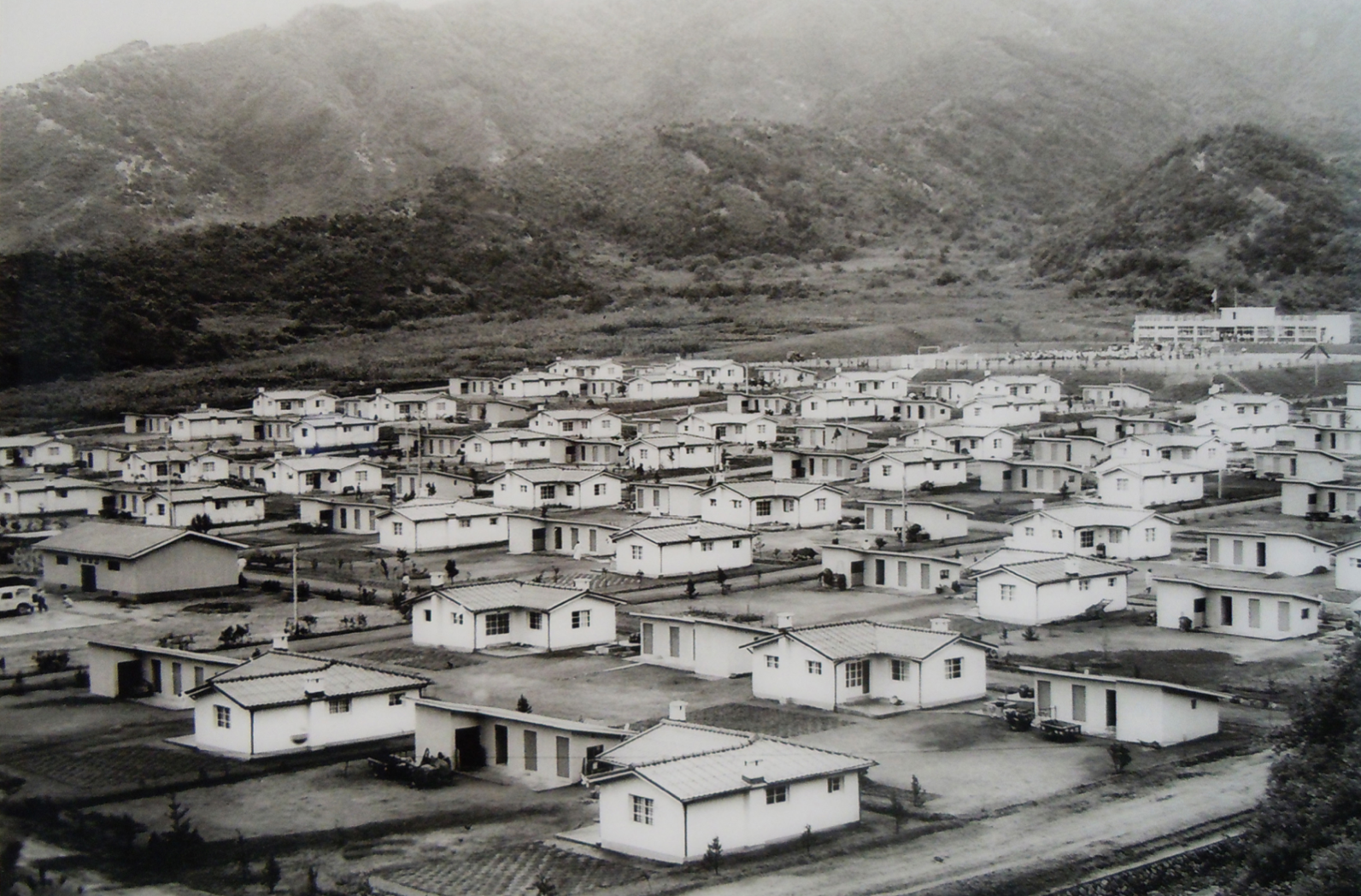

Photo credit: Alice Evans

About the author

Alice Evans is an LSE Fellow in Human Geography at the Department of Geography and Environment, London School of Economics and Political Science.

A Note on the Research and Results

Her research introduced in this post was to examine the factors accounting for the increased prioritisation of maternal health care in Zambia, at national and district levels. Looming failure to achieve this Millennium Development Goal and thereby successfully partake in the global development project appears to have been a key factor here, motivating top-down pressure to improve maternal health indicators. A couple of her TV interview clips can be found on these links: Clip 1 and Clip 2. Her paper on ‘History lessons for gender equality from the Zambian Copperbelt, 1900–1990’ is forthcoming in the journal Gender, Place and Culture.