By Bernhard Dachs (Austrian Institute of Technology) and Stefan Pahl (University of Groningen)

By Bernhard Dachs (Austrian Institute of Technology) and Stefan Pahl (University of Groningen)

Global value chains (GVCs) have been a dominant trend in the world economy since the 1970s, but more recently their growth appears to be stagnating. In this article Bernhard Dachs and Stefan Pahl explore the roles of shifting global demand, backshoring, and regional integration in Asia in explaining this slowdown.

To sum up, the expansion of global value chains is of the defining trends in the world economy since the 1970s. Today, we see some signs that this trend has slowed down or even stopped. This is not just the result of policy-driven de-globalization in the form of Brexit, trade wars, or ‘America First’. Shifts in global demand, stronger regional integration in Asia, and backshoring of production activities to the home countries contribute to this trend. New production technologies can support backshoring if they increase productivity, quality and flexibility. If a firm can produce at similar costs in Europe and enjoy a higher flexibility because of the local ecosystem and proximity to clients, backshoring becomes a feasible option. As a consequence, more new technologies may lead to less fragmentation and more local production in the future.

The growth of global value chains (GVCs) and the fragmentation of national production has been one of the constitutive trends in the world economy over the last 40 years (Baldwin 2016; Pahl and Timmer 2019). International expansion first took place in Europe and in the US; since the year 2000, the attention of multinational firms increasingly turns to Asian markets.

New evidence suggests that the growth of GVCs is slowing down or has even stopped. The recent World Investment Report by UNCTAD shows that global foreign direct investment (FDI) flows fell by 13% in 2018 compared to 2017. This is just the last of several disappointing years since the global financial crisis. This stagnation is also confirmed by data on the economic activities of EU and US multinational enterprises (MNEs) collected by Eurostat and the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).

Additional indication for a slowdown in the expansion of GVCs comes from the use of imported production inputs in exports. The OECD Trade in Value-Added (TiVA) database includes input-output data for 64 economies and 36 industries which are linked at industry level via imports and exports to allow the analysis of changes in demand, production structure, etc. across countries. We use this data to measure how much foreign value-added countries use in their manufacturing exports, expressed as a share of their gross exports. The higher this share, the more foreign value-added is needed for the production of exports and, thus, the higher is the degree of product fragmentation in global value chains. To depict the trend of vertical specialization over time, we regress the foreign value-added content as a share of gross exports in manufacturing on time and country dummies.

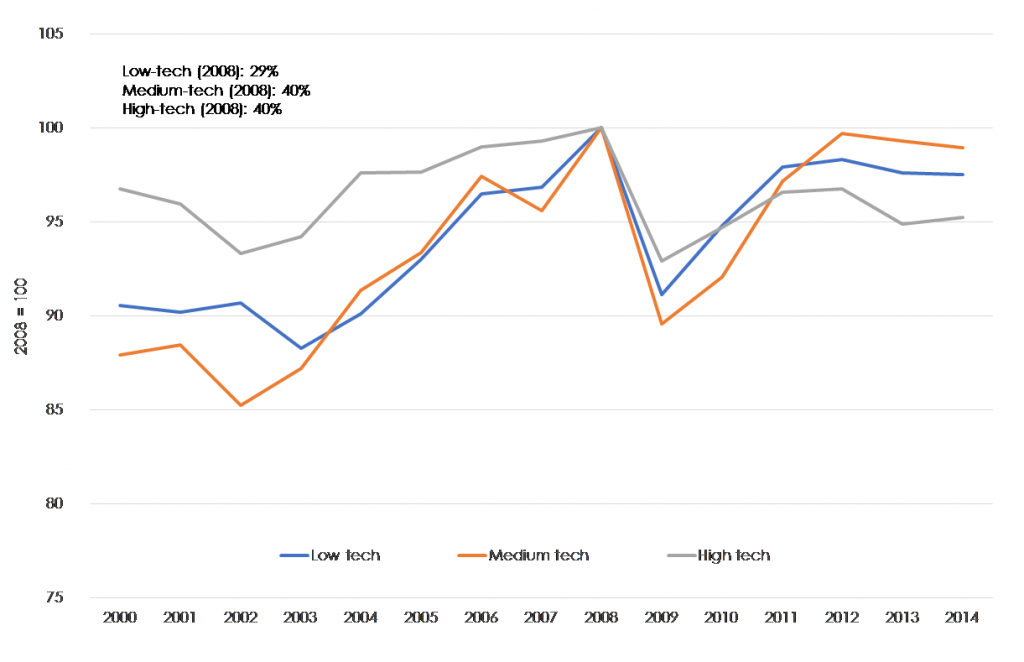

Results indicate that the foreign value-added content in exports drops sharply in 2008/09 (see Figure below). Production fragmentation recovers after 2009, but six years after the crisis, the average foreign value-added content in exports still remains below the level of 2008. In particular, fragmentation in high-technology industries such as machinery or automotive is lower in 2014 than before 2008. Differences in foreign value-added content are smaller in 2014 than they are in 2000.

Foreign value-added content in manufacturing exports for high-technology, medium-technology and low technology sectors, 2000 – 2014

Source: OECD TiVA database.

Market saturation and a lack of promising opportunities have their part in this development. In its World Economic Outlook 2016, the IMF sees sluggish demand for investment goods relative to non-tradeable services as a main reason for stagnating imports relative to world GDP since the crisis. The share of high-technology sectors on total exports dropped by 1.5 percentage points between 2008 and 2014. The digitalization may lead to a substitution of flows of physical goods by flows of data.

A second important factor is a lower level of fragmentation in Chinese manufacturing (Timmer et al. 2016). China’s share on global demand has been growing fast, but Chinese firms today require fewer imports since more and more inputs are produced domestically. Moreover, Chinese firms are building up their own supplier networks in Southeast Asia (UNIDO 2018).

Finally, there is also evidence that firms actively move back production to their home countries. This strategy is known as ‘backshoring’ or ‘reshoring’ in the literature. The number of backshoring firms is still small; however, decreasing labor cost advantages of Asian countries and an ‘overstretching’ of value chains which reduced flexibility and the ability to satisfy demand in short time may foster backshoring in the future (Dachs et al. 2019). New digital production technologies, such as Smart Manufacturing, Industrie 4.0, or the Internet of Things may even foster backshoring. These technologies can help firms to increase productivity, product quality and flexibility, and allow more local production in proximity to customers in Europe and the United States (Dachs et al. 2017). Low income countries which are not yet part of GVCs, however, may find it increasingly difficult to enter global markets in the future because their labor force is often lacking the skills needed to master new production technologies.

To sum up, the expansion of global value chains is one of the defining trends in the world economy since the 1970s. Today, we see some signs that this trend has slowed down or even stopped. This is not just the result of policy-driven de-globalization in the form of Brexit, trade wars, or ‘America First’. Shifts in global demand, stronger regional integration in Asia, and backshoring of production activities to the home countries contribute to this trend. New production technologies can support backshoring if they increase productivity, quality and flexibility. If a firm can produce at similar costs in Europe and enjoy a higher flexibility because of the local ecosystem and proximity to clients, backshoring becomes a feasible option. As a consequence, more new technologies may lead to less fragmentation and more local production in the future.

References

Baldwin, R.E., 2016. The Great Convergence: Information Technology and the New Globalization. Belknap Press, Cambridge [Mass.].

Dachs, B., Kinkel, S., Jäger, A. 2017, Bringing it all back home? Backshoring of manufacturing activities and the adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies. MPRA Paper No. 83167, https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/83167/

Dachs, B., Kinkel, S., Jäger, A., Palčič, I., 2019. Backshoring of production activities in European manufacturing. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2019.02.003

Pahl, S., Timmer, M.P., 2019. Patterns of vertical specialisation in trade: long-run evidence for 91 countries. Review of World Economics, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-019-00352-3

Timmer, M.P., Los, B., Stehrer, R., De Vries, G.J., 2016. An Anatomy of the Global Trade Slowdown based on the WIOD 2016 Release. GGDC Research Memorandum 162, Groningen.

UNIDO 2018, Global Value Chains and Industrial Development: Lessons from China, South-East and South Asia, UNIDO, Vienna, https://www.unido.org/sites/default/files/files/2018-06/EBOOK_GVC.pdf