By Rasmus Lema (Aalborg University), Carlo Pietrobelli (University Roma Tre and UNU-MERIT), Roberta Rabellotti (University of Pavia), and Antonio Vezzani (University Roma Tre).

By Rasmus Lema (Aalborg University), Carlo Pietrobelli (University Roma Tre and UNU-MERIT), Roberta Rabellotti (University of Pavia), and Antonio Vezzani (University Roma Tre).

Examining innovative capabilities in 45 countries through a focus on Information Technology, the authors find an interesting divergence between the hardware and software sub-sectors, suggesting that the GVC-innovation link is not as straightforward as many assume.

——-

Global Value Chains (GVC) participation & innovation in IT

The IT industry is highly innovative and deeply influenced by GVC trade. About 40% of R&D investments by the top R&D investing companies worldwide are in IT. Furthermore, the spread of digital technologies, together with the reduction in transport and communication costs, has favoured the reorganisation of international production and business models, along with the rise of GVCs in IT.

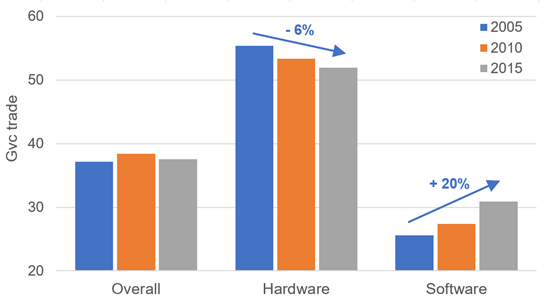

Looking at Figure 1, in 2005 GVC trade was particularly high in the hardware sector, while in software it was lower. Since then, the two sectors have moved in opposite directions: GVC participation has decreased in hardware (-6% between 2005 and 2015) and strongly increased in software (+20%).

Note: Share of trade in intermediaries over total trade.

Source: Authors’ elaboration from TIVA-OECD data.

In terms of innovation capacity, differences between the two sectors have been especially marked. In terms of patents filed at USPTO in 2015, the hardware sector accounts for 44% of the total and the software one only for 2.4%. Nevertheless, between 2005 and 2015 patents in software almost doubled (+90%), experiencing a much higher growth rate than in hardware (+26%).

What explains the differences between hardware and software?

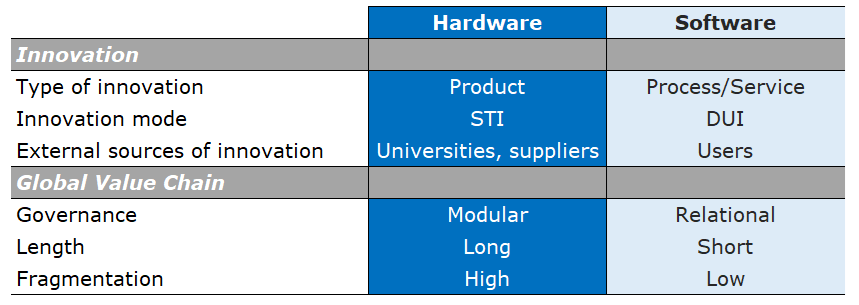

The hardware and software industries are very different in terms of the prevailing characteristics of innovation and GVC integration, summarised in Table 1 below.

Note: STI: Scientific and Technological-based Innovation; DUI: Learning by Doing, Using and Interacting. Source: Authors’ adaptation from Castellacci (2008) and UNCTAD (2020)

The hardware sector is largely characterised by product innovation based on codified scientific and technical knowledge, which can be globally accessed to solve local problems. The codification of knowledge enables firms to innovate regardless of their GVC position. The possibility to codify specifications and the modularity of products allow for the independent development and production of specific components. Codification and standardisation thus reduce asset specificity and the need for buyers to control and interact with its suppliers directly.

The software sector, by contrast, is characterised by the acquisition of tacit knowledge based on learning and experience and requires strong interdependence with users. As a result, GVCs are characterised by complex (relational) interactions among players who can create mutual dependences and dense knowledge exchanges.

GVC & innovation trajectories in IT

Based on an industry-country level dataset combining information from the Trade in Value Added (TiVA) database produced by the OECD and USPTO which provides information on patents, we reach the following main findings.

- Countries with initially well-developed innovation capacity experience a greater increase in patenting activity, hinting to a strong cumulativeness of the innovation process in the IT industry. This also implies that countries lacking such initial capabilities find it more difficult to catch up with international leaders. In other words, the IT industry benefits from increasing knowledge returns to innovation.

- In the hardware sub sector, increased innovative capacity is associated with decreased GVC participation. This can be explained by the ability to codify and separate production from innovation in this sector. Deepening of innovative capacities thus depends less on integration into GVC and de-globalisation (reshoring), and there are few implications about continued innovative capacity. Conversely, suppliers may move deeper into GVCs without gaining significant access to critical tacit knowledge.

- In the software sector, by contrast, the strengthening of innovative capacity is significantly correlated with increased participation in GVCs. This can be explained by the continued dependence on user-producer interaction for innovation in the software and IT-enabled services sector.

- Some countries (Finland, Israel, South Korea and USA) are able to leverage synergies between hardware and software and appear among the most dynamic in both sectors. Therefore, dynamism in hardware may be fostered by a dynamic software sector, and vice versa.

Take-home messages

IT is characterised by strong cumulativeness in the innovation process that may lead to an increasing concentration in innovation capacity in some of countries. Indeed, our evidence shows that leading countries have strengthened their innovative capacity relative to others, calling for some reflection on the possible effects on the worldwide catching-up process.

However, hardware and software sectors are characterised by differences in the way GVCs and the innovation process are structured. In general, it’s only in the software sector where GVC participation and strengthening of the innovative capacity seem to go hand in hand. The increasing relevance of GVC trade in software calls for a better understanding of GVC-innovation linkages in knowledge intensive business services.

Some countries have been able to reinforce their innovative capacity in both the hardware and software sectors, suggesting that they may be in a better position to leverage the complementarities deriving from the recombination of hardware and software triggered by platforms and industry 4.0 technologies. National systems of innovation do not seem to have the same capacity to foster and exploit these synergies. A finer-grained analysis to understand the synergies (or lack of them) among different subsystems is needed. New, unexpected windows of opportunity may emerge from the development and integration of physical and virtual systems. However, our findings suggest that strong innovators have been more successful in integrating hardware and software capacities, possibly because they enjoy key ownership stakes in platforms, providing access and capability to leverage knowledge and orchestrate innovation networks.

The GVC-innovation link is not straightforward, as is sometimes assumed. There are studies showing a positive correlation between GVC participation and innovation but as we show that there are important exceptions. The plurality of patterns observed, reflecting a complex and dynamic relationship between GVC participation and innovation, calls for further research to understand the role of specific factors that may lead to successes or failures in global knowledge intensive industries.

Contributors

Rasmus Lema is Associate Professor at the Aalborg University Business School

Carlo Pietrobelli is Professor at the University Roma Tre Department of Economics

Roberta Rabelotti is Professor at the University of Pavia Department of Political and Social Science

Antonio Vezzani is Assistant Professor at the University Roma Tre Department of Economics

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the GILD blog, nor the LSE.