By Francesco Lissoni (University of Bordeaux) and Ernest Miguelez (University of Bordeaux)

By Francesco Lissoni (University of Bordeaux) and Ernest Miguelez (University of Bordeaux)

The authors find that innovation hotspots are more successful when they host a larger proportion of migrant inventors. Their role compares to organization-based pipelines, but this success is overwhelmingly seen in northern America and Europe, and in the largest clusters.

The golden age of globalization has coincided with the rapid growth of the international migration of highly skilled people, especially those with education and/or jobs in Science, Technology, Engineering or Mathematics (STEM). International migrants’ personal ties matter, whether strong, such as kinship or personal friendship, or weak, such as relationships loosely based on common educational background or cultural traits.

Identifying innovative hotspots worldwide

Drawing on earlier work, we first geolocalise worldwide patent data (all Patstat, not limited to single patent offices) and scientific publications (from Web of Science) to detect 487 innovation hotspots in 34 countries. These are typically large urban areas, such as Beijing, London, Los Angeles, New York, Seoul, and Tokyo, which concentrate a large number of patents and publications, but also Buenos Aires, Delhi, Istanbul, Mexico City, Moscow, Sao Paulo, Tehran, Cairo, Bangkok, Kolkata, and Chongqing, which host innovative agglomerations of lesser importance, though growing. Figure 1 shows the identified innovation hotspots in North America, Europe and East Asia.

Figure 1. Identified innovation agglomerations

Do countries internationalise their inventive activity?

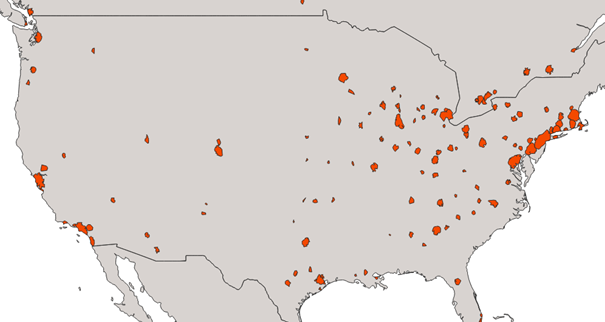

Next, we measure internationalisation through patent teams’ geographical dispersion, as observed when the inventors of the same patent have addresses in different countries. For MNCs’ patents, such dispersion may result from the distribution of R&D activities across laboratories in different countries, or from collaborations between the patent applicants and foreign research entities. Figure 2 (left panel) shows the trends for international collaborations for the whole world (dashed line) and for a selection of countries, starting in 1991. We see that international co-invention increases over time, but not monotonically. We also see that international collaboration trends differ widely across countries, with East Asian countries exhibiting the lowest collaboration levels. Next, Figure 2 (central panel) shows that India stands out as a country with greater foreign penetration, as measured by the share of locally-invented patents held by foreign companies. By the end of our period of analysis, almost 60% of patents with inventors in India have at least one foreign applicant. By contrast, China exhibits similarly large shares only at the start of the observation period: as soon as its inventive activity starts growing, its foreign share goes down to around 15%.

From the whole universe of patents in Patstat, we estimated the share of inventors with likely foreign origin. We use IBM’s Global Name Recognition system (IBM-GNR) to estimate a likely migratory background of the inventors. Figure 2 (right panel) shows that the worldwide weight of migrant inventors has increased incessantly since the late 1980s (dashed line). The US is both the most important destination country, and the country with the highest inventor immigration rate. The trend is similar in the UK and, at to a lesser extent, in France and Germany. Some English-speaking countries such as Canada and Australia (not included in Figure 2) have trends and levels comparable to those of the US. The same applies to small, R&D intensive European countries such as Switzerland and the Netherlands. India and China start with very high immigration levels, which later on decline incessantly. Most likely, the trend inversion is due to the prevalent nature of STEM immigration in such countries, which mostly consists of foreign researchers working at local MNCs’ branches. These weighed considerably on the inventor population when the indigenous innovative activity was limited, and much less thereafter.

Figure 2. Share of immigrant inventors, total and by destination country; 1976-2015

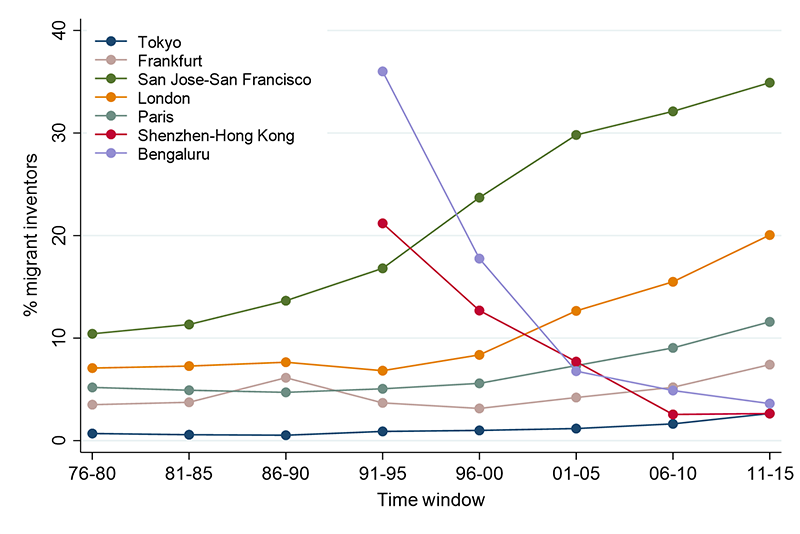

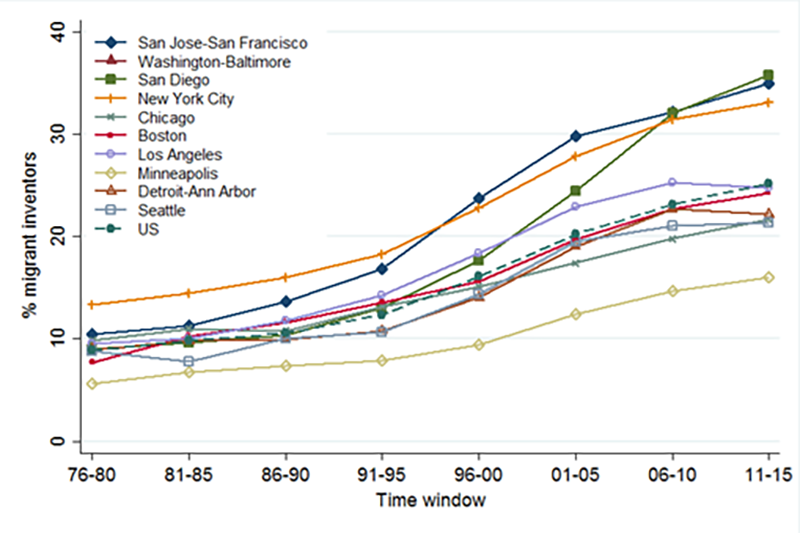

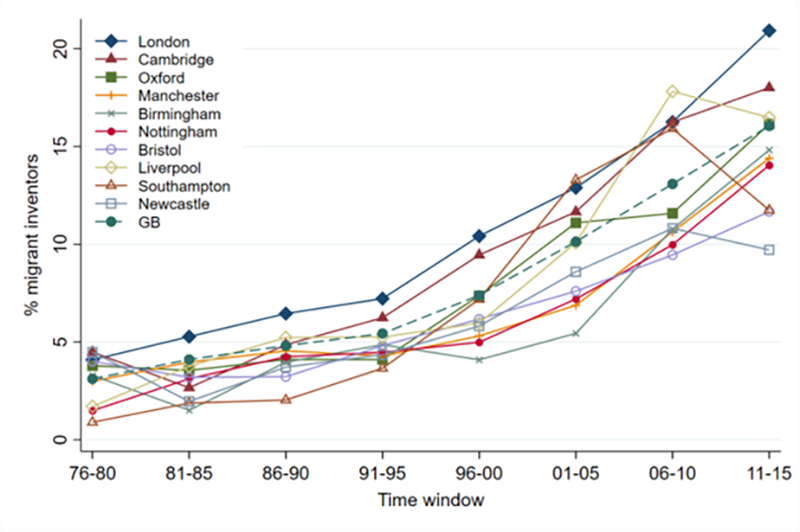

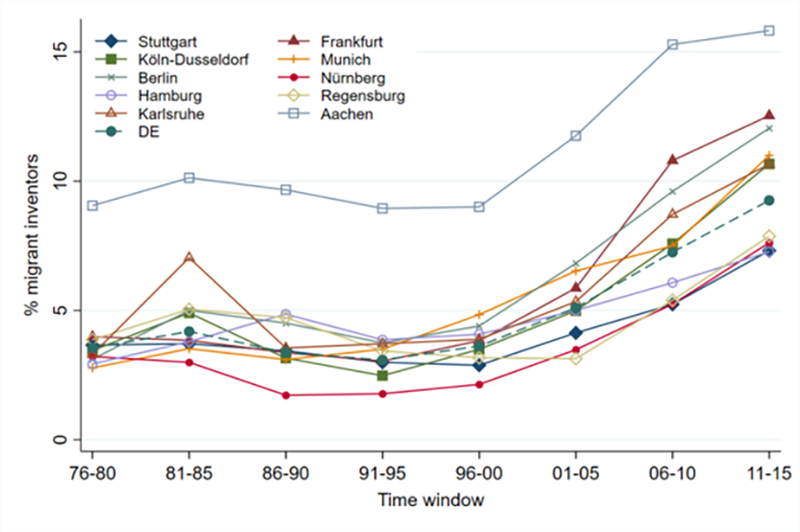

Figure 3 reports information for the largest clusters in a selection of countries. Local and national trends are similar, but levels are different, especially cities such as San Jose-San Francisco, London, Paris or Frankfurt, whose immigration rates are well above their national averages. As for Tokyo, it exhibits steadily low migration rate levels. Looking closer at the US (right-top panel) we notice that three agglomerations, San Francisco, San Diego and New York, have 50 percent larger migration rates than the country as a whole. Two other West and East coast agglomerations (respectively Los Angeles and Boston) also stand out. Data for the UK show that, besides London, the two agglomerations with above-average immigration rates are those most clearly associated with academic research and its transfer (Cambridge and Oxford). As for Germany, the most interesting case is that of Aachen, which stands next to both the Netherlands and Belgium and receives commuters from both countries, thus illustrating the importance of intra-European migration, especially in border cities such as Eindhoven or Brussels (not included in Figure 3).

* As per 2011-15 ranking

Clusters’ success and global pipelines

Based on the above data, we can investigate how much of a hotspot’s success is due to the organisational or personal global pipelines to which it is connected. We find that:

- Hotspots hosting a larger proportion of migrant inventors have greater success. An additional percentage point in the share of immigrants’ inventor-patent pairs goes along with a 0.07% increase in the number of per-capita patents in the average hotspot-technology pair; and that the effect goes to 0.12% when weighing patents with the citations they receive. These effects are comparable, from a quantitative viewpoint, with those pertaining to organisational ties, in particular international collaborations.

- The positive relationship between inventors’ migration and productivity is due almost entirely to the top-25 largest clusters in each technology, and among them, those based in North America and Europe. Meanwhile, non-top-25 clusters and those located in South and East Asia barely benefit from the presence of foreign-origin inventors.

- As for MNC presence, this is unrelated to cluster centrality, and negatively related to productivity. This would suggest a positive association between the strength of domestic firms’ presence and the cluster’s success.

Takeaway message

While confirming, with some qualifications, the importance of organisational-based global pipelines, our results also point to the crucial role of migration-based ties. When immigration is taken into account, migrant inventors play a role in the success of the largest hotspots in English-speaking and European countries, the former being the most important destination of STEM migrants worldwide (and in particular those from Asia), the latter being beneficiaries of the European free-movement area. However, lesser hotspots in Asia neither attract migrant inventors, nor do they appear to benefit much from their presence. Deciding whether the two phenomena go hand in hand, perhaps because impacts of migrants’ presence might be felt only above a certain threshold, is something to investigate in future research.

This post is based on the chapter “The missing link: international migration in global clusters of innovation”, by Massimiliano Coda-Zabetta, Christian Chacua, Francesco Lissoni, Ernest Miguelez, Julio Raffo, Deyun Yin, accepted for publication by Oxford University Press in the forthcoming book “Cross-border Innovation in a Changing World. Players, Places and Policies”, edited by D. Castellani, A. Perri, V. Scalera, A. Zanfei due for publication in 2021.

*****

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the GILD blog, nor the LSE.

Francesco Lissoni is Professor of Economics at the University of Bordeaux

Ernest Miguelez is Research Fellow at the University of Bordeaux