by Sarah Giest (Leiden University)

by Sarah Giest (Leiden University)

This article suggests changing the cluster narrative around the importance of locality, life cycles and the focus on one industry and instead looking at the underlying mechanisms of collaborative and absorptive capacity driving innovation dynamics in and beyond clusters. This enables government in collaboration with cluster organisations to facilitate features of clusters in a more flexible way while recognising the multi-level and multi-stakeholder nature of innovation.

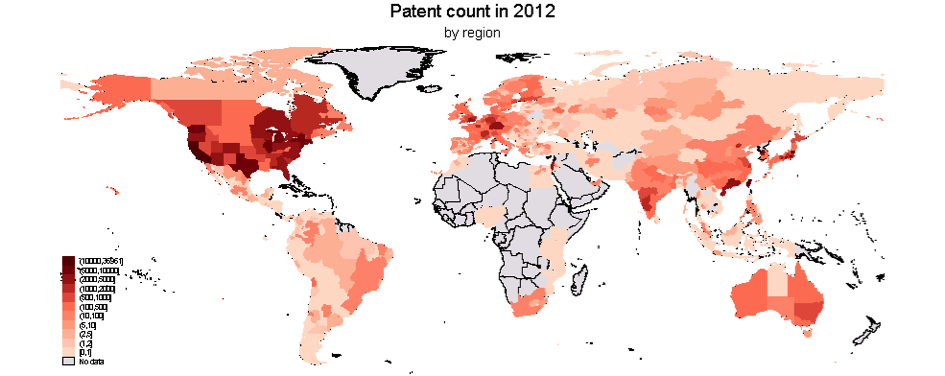

Innovation clusters have been ‘en vogue’ since rising to popularity, most notably in the context of Silicon Valley. The idea that co-location of research and industry stakeholders creates high levels of innovation has since then spread beyond California, and Silicon Valley remains a blueprint for many of the initiatives undertaken in other parts of the world. Not all of these attempts are successful however.

There is an ongoing discussion around whether and how governments can facilitate such local innovation. So-called ‘cluster policy’ is a complex undertaking – it involves multidimensional considerations around financial stimuli as well as local attractiveness, leading to a diverse set of policy instruments and informed by a combination of rationales rooted in industrial, regional and innovation policies. At the same time, it is a challenge for governments to balance immediate needs of clusters with long-term goals while ensuring regional economic integration.

In this context, there are preconceived notions around what innovation clusters are and how government – both national and local – can support them. These notions consist of three main arguments: (1) that locality is a key feature of innovation, meaning that proximity affects networking among stakeholders and thus creates synergies for innovation; (2) that clusters evolve along a so-called ‘life cycle’ model where they undergo reinvention and transformation; and (3) there is a focus on reinforcing existing or established industries.

None of these assumptions are wrong, as they address the main characteristics of innovation clusters, however, they have dominated the policy dialogue and created bottlenecks from the perspective of public support. Looking at how policymaking works in combination with the dynamic of local innovation networks, there is evidence that the importance of location, cluster life cycles and the focus on one industry is limiting cluster potential. The research in the author’s book[i] suggests that there is an opportunity to reframe this ‘cluster narrative’ and develop a focus on underlying capacity mechanisms that enable more flexible support in a collaborative effort with cluster organisations.

Capacity to innovate

Academic discourse points to the importance of capacity (e.g., Lundvall et al. 2003; Lindqvist et al. 2013; Trippl et al. 2015; Murphy et al. 2014)[ii], though without it being a focal point in the discussions around clusters. The premise of the capacity idea is that collaboration and knowledge transfer are central elements of innovative dynamics within clusters. Capacity can be defined as the ability of private or public organisations, and of the network, to absorb and use knowledge relevant for innovation processes. This separates capacity from other concepts such as resilience or adaptability, in that it focuses on the social capital and networking structures within local settings. Along these lines, capacity is understood as collaborative and absorptive capacity, where collaborative capacity describes the networking elements of innovation, such as structure, resources, and communication, while absorptive capacity describes the ability to integrate and exploit knowledge from inside and outside the cluster.

Given these arguments, the capacity idea sheds new light on the standing cluster narrative of location, life cycles and one industry, in addition to highlighting the role that cluster organisations play in organising knowledge-sharing activities and supporting government in implementing cluster policies. For the latter argument, cluster organisations come in different shapes and forms, but generally offer services and support the coordination and development of joint projects within a cluster. This means they can potentially compensate for limited capabilities in the cluster by facilitating collaborative and absorptive capacity elements. They are also a point of contact for government to better understand current needs in the cluster.

A focus on capacity also allows for an alternative way of framing the current cluster narrative. For the relevance of location, the central argument of absorptive capacity is that cluster stakeholders can compensate for resources lacking within the cluster by tapping into knowledge sources elsewhere. This implies that both cluster organisations and policymakers need to look beyond the local setting and look at strategies fostering, for example, the inflow of human capital or fostering international research and development (R&D) collaborations. In fact, globalisation has forced governments and industry to identify the competitive advantage of places at an international level – an advantage rooted not only in output performance, but also in the effectiveness of networking, knowledge exchange and links between local and global players.

Further, the life cycle model used for clusters might not be useful when targeting capacity elements. The core assumption of clusters going through phases in combination with a temporality argument is hard to address for policymakers, as policies are often layered as well as hard and slow to change. Stripping these dynamics down to capacity-building elements makes them easier to target.

Finally, given that innovation in clusters is made of many different aspects around capacity, some policies might need to disconnect from an industry-driven approach and look more closely at the characteristics of the cluster in question. Most cluster policies are designed to reinforce regional strongholds and to encourage further specialisation, while cluster policy often requires a broader and more comprehensive understanding of both innovation dynamics and the cluster.

To conclude, given the dynamic setting of clusters and the stakeholders within them, policy needs to be sufficiently flexible to set a frame in which clusters can flourish with more general policies that look at the competitiveness of a cluster on the global stage, as well as to support capacity elements that are specific to the regional and cluster set-up. This comes with a shift in the understanding of the policy target from a single goal or performance indicator to sustaining an innovation ecosystem. This is done through a deep knowledge of the region – by connecting to cluster organisations who often possess such knowledge – in combination with repositioning of the region in the global value chain.

***

This article is based on the recently published book ‘The Capacity to Innovate’ with the University of Toronto Press, which includes a cross-sector survey of government, industry and research stakeholders in clusters around the world as well as case studies of four biotechnology clusters with varying levels of government involvement and cluster management visibility: Chicago, Medicon Valley, Singapore, and Vancouver.

Sarah Giest is an Assistant Professor in the Institute of Public Administration at Leiden University. Her research focuses on the role of government in using and facilitating new technologies.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the GILD blog, nor the LSE.

[i] Giest, Sarah. 2021. The Capacity to Innovate, Cluster Policy and Management in the Biotechnology Sector. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

[ii] Lundvall, B.-A., B. Johnson, E. Andersen, and B. Dalum. 2003. ‘National Systems of Production, Innovation and Competence Building’. Research Policy 31 (2), 213-231.

Lindqvist, G., C. Ketels, and Ö. Sölvell. 2013. The Cluster Initiative Greenbook 2.0. Stockholm: Ivory Tower.

Trippl, M., B. Asheim, and J. Miorner. 2015. ‘Identfiication of Regions with less developed Research and Innovation and Innovation Systems’. Papers in Innovation Studies 2015/1. Lund, Sweden: Lund University, Centre for Innovation, Research, and Competence in the Learning Economy.

Murphy, L., R. Huggins, and P. Thompson. 2016. ‘Social Capital and Innovation: A comparative analysis of regional policies’. Environment and Planning: Government and Policy C 34 (6), 1025-57.