In the last of our three-part series on China, the department considers the demographic implications behind the decision to repeal the one-child policy. Will families want to enlarge their families? Should the state maintain control over population growth? Find out below.

Time for a change – Jude Howell

After more than three decades of one-child policy, it was time for change. Indeed, Chinese demographic scholars had long been advising the CCP to alter course. It could no longer be overlooked that China’s One-Child Policy had led to a number of demographic and developmental distortions. It has entrenched cultural preferences for a son, spurred child-trafficking, and fuelled an industry of pre-natal sex identification.

After more than three decades of one-child policy, it was time for change. Indeed, Chinese demographic scholars had long been advising the CCP to alter course. It could no longer be overlooked that China’s One-Child Policy had led to a number of demographic and developmental distortions. It has entrenched cultural preferences for a son, spurred child-trafficking, and fuelled an industry of pre-natal sex identification.

The outcome has been an unsavoury sex imbalance ratio of 119 males to 100 females (with 105 males being the global average), and a surplus of well over 30 million single males desperate to maintain the ancestral line and meet social expectations. It has contributed to a rapidly ageing population that the UN estimates will rise to almost 440 million by 2050. Overzealous implementation of the policy at lower levels has led to egregious violations of the reproductive rights of women.

Jude Howell is Professor in International Development and convenor of the DV432 module, ‘China in Developmental Perspective’.

Not all families will have more children – Elliott Green

There is some evidence suggesting that this shift might be too little, too late as regards Chinese demography. Rapid urbanization and higher living costs mean that many Chinese families might not choose to have two children even if they are allowed to do so. Indeed, Hong Kong and Singapore, both of which have majority Chinese populations without any government limits on fertility, saw their average number of births per women decline below 2 around 1980 to a level around 1.3 today.

China’s missing women and skewed sex ratios are not entirely due to the one-child policy, inasmuch as other countries like India suffer from the same problem; similarly, South Korea’s success in rectifying its sex ratios over the past 25 years arguably had more to do with industrialization, female education, rising marriage ages for women, urbanization and democratization than state policies towards fertility.

Elliott Green is Associate Professor of Development Studies and convenor of the DV442 module, ‘Key Issues in Development Studies’

See Part 1 of our Response: How Revolutionary?

Baby Boom could spell catastrophe for China – Kate Meagher

The worries of an ageing population, the tightening of the labour market, and the will of the people are no doubt part of the story, but one can’t help having a sense that the people at the top have been watching these factors and taking action in an incremental way all along.

The worries of an ageing population, the tightening of the labour market, and the will of the people are no doubt part of the story, but one can’t help having a sense that the people at the top have been watching these factors and taking action in an incremental way all along.

While the authoritarian, sometime draconian, mode of implementation is a matter of genuine concern, and has had severe consequences for individuals as well as society as a whole, single issue campaigners would do well to think carefully about the complex range of issues at stake in Chinese population policy.

A sudden and total withdrawal of China’s controls on child numbers could make the West’s Post-War Baby Boom look like a whimper. Societies as concerned about the link between demography and productivity as China know too well how catastrophic huge swings in population policy could be to the country’s economic and social wellbeing.

While Western development policy is fond of big pushes and shock therapies, China’s gradual easing off of restrictions on child numbers may be the better part of wisdom.

Kate Meagher is Associate Professor in Development Studies, convenor of the DV433 module, ‘The Informal Economy and Development’, and director of the MSc in Development Studies for 2015/16.

Good news for Chinese girls – Keith Hart

Asia currently accounts for 60% of the world’s population, Africa 15% (double its share in 1900). UN forecasts predict that Asia’s share in 2100 will be 42%, Africa’s 40% and everywhere else 18%. This is because Africa is the only region whose population is increasing (2.5% a year) whereas all the rest are in decline (ageing).

In the light of global demographic history, this policy change is unlikely to reverse the trend. But it is good news for Chinese girls.

Keith Hart is Centennial Professor of International Development & Anthropology and co-convenor of the DV451 module, ‘Money in an Unequal World’.

The population dynamics question – Danny Quah

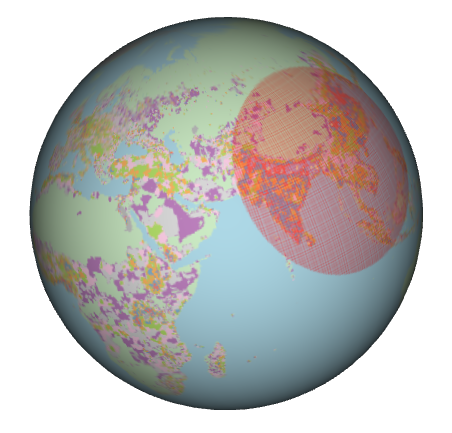

The following piece of evidence might be relevant on the China population dynamics question. I performed a calculation on the world’s populations, and there’s a simple picture that captures my principal point.

If you ask where the smallest circle on Earth is that includes a majority of the world’s population [remember this isn’t just where there are lots of people, it’s where the *smallest* circle is that includes more people inside than there are outside], which is that circle 3,300km in radius centred on the Shan State in Myanmar, right on China’s western boundary. The circle excludes Japan, incidentally. I explain how this calculation is done here and talk about some of the implied geopolitics.

That smallest circle today already includes China. So my two-cents’ worth prediction: the circle will shrink and drift East.

Danny Quah is Professor of Economics and International Development, and Director of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre. The full analysis is available on his blog.

See Part 2 of our Response: The Economic Transformation

Rapidly declining population should be avoided – Tim Dyson

Despite its catchy title, fertility in China did not fall from around 6 births to reach a low level because of the so-called ‘One Child Policy’. Instead, fertility was reduced mainly by the ‘Later, Longer, Fewer’ campaign of the 1970s. ‘Later, Longer, Fewer’ meant: Later childbearing (so inter alia increasing the population’s generational length); Longer birth intervals, and Fewer children overall. The Later, Longer, Fewer campaign was highly coercive, but very effective. By the time the One Child Policy was introduced in 1979, fertility in China was probably close to 2.5 births per woman.

In a 1997 paper titled ‘Population policy: Authoritarianism versus cooperation’, published in the Journal of Population Economics, Amartya Sen compared fertility trends in China with those in the Indian state of Kerala. On the basis of this comparison, he argued that voluntary processes can have as substantial and rapid an effect in lowering fertility as coercive measures. Curiously, however, his base year in the comparison was 1979 – i.e. the start of the One Child Policy – by which time coercive measures had been in place for nearly a decade, and most of the fertility decline had already happened.

Most people, me included, would agree that China’s steps to reduce its fertility in the 1970s were much too strong, and that they had some very unfortunate effects. Nevertheless, fertility decline has also had some beneficial effects for China’s people, for just one aspect of this see Bloom and Williamson’s 1998 paper in the World Bank Economic Review. It is also interesting to note that if India had experienced China’s fertility trajectory since 1970 then its population would probably not have exceeded one billion.

However, India’s population today is already about 1.25 billion and it will almost certainly reach about 1.6 billion in the next 35 years. Over the longer run, then, the timing and speed of fertility decline can make a huge difference to population size (and structure). Many Indian demographers believe that their country’s people would generally be better-off in all sorts of ways if fertility had come down faster than it has (especially in the north).

Finally, coming back to China, although it is hard to be certain of the true level of fertility, the Chinese demographers I know have been concerned for some time that the actual level of fertility in the country is significantly lower than the official estimates accepted by the government. The UN puts the current level of fertility at only about 1.55 births. At such low levels, very small differences have major differences over the long run. Thus 1.9 births per woman has hugely different consequences to 1.5 births.

What should certainly be avoided is a rapidly declining population – which, if it became established, would be very hard to reverse. Hence, at least in part, the present efforts to raise fertility.

Tim Dyson is Professor of Population Studies and convenor of the DV411 module, ‘Population and Development’.

Related Posts

![Tim Dyson, Professor of Population Studies, LSE gives a keynote presentation on Population Dynamics and Sustainable Development. United Nations Headquarters, New York. UN DESA/S. Nijman [http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/commission/sessions/2015/]](https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/internationaldevelopment/files/2015/07/TimDysonUNOfficial-300x159.jpg) |