Last month members of the LSE DESTIN Society attended the 2016 Bond Conference to hear speakers from across the globe talk about some of the most pressing issues in international development. One of those in attendance was MSc Development Studies student Meredith MacKenzie, who has shared some of her thoughts with us on one of the topics covered, development and social media.

By far the most interesting voices of the 2016 Bond Conference were southern ones. Attendees and speakers from countries of the Global South were the fiercest and most compelling in the line up as they confronted the opportunities and challenges that NGOs and foreign development agencies present in their countries. Their witness to the conference began in the very first session. Aya Chebbi, a Tunisian activist and youth leader spoke during the opening session and implored the NGO members of Bond, “Speak to us, not about us.” This idea continued in the breakout sessions on campaigns and media. The speakers who led these sessions on social media, online activism and the role of global processes repeated this idea that people are not recipients of aid, but they are the agents of their own development if only the development industry would see them as such.

If there’s anything I learned its that revolution will be live-streamed, tweeted and shared (and in some ways it already has been). The session “#breaktheinternet,” consisting of five-minute, lightening-round trainings on effective social media not only had the cleverest name, but offered concrete examples of how we can do online and social media campaigns better in the development field. This and the session on how to build winning movements, especially online, made it clear that development organizations have a lot to learn from local civil society and social movements focused on goals other than development.

I came to LSE having worked a for a decade in media and communications. As a congressional press secretary I helped run social media accounts for high ranking government officials and then later at a media strategy firm I designed actions for advocacy campaigns targeting those same high ranking officials. I have seen how social media accounts can be a way of sharing essential information and unfortunately disinformation. As I transition to the development field, I believe it is essential that the development community, and all the stakeholders in aid decisions, start doing social media communications better and doing it differently. We need to move beyond grainy filtered photos of sick and dirty Black children in our Facebook feeds and urgent messages crafted to inspire pity and guilt in our inboxes. This type of communication perpetuates top-down, hand-out aid paradigms that ignore the need for subsidiarity and economic development that is brought about and sustained by local communities.

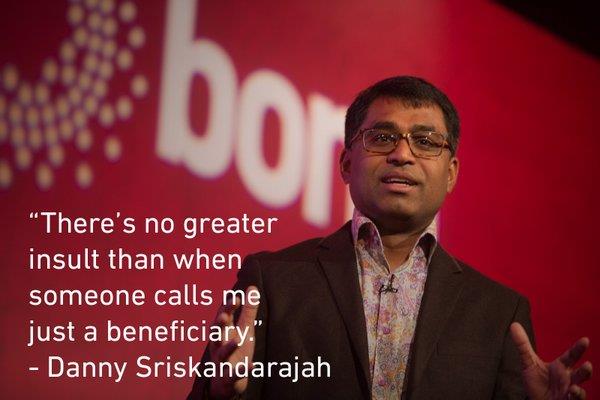

Another speaker who encouraged development organizations to think and act differently was Danny Sriskandarajah of the CIVICUS Alliance, global network of civil society organizations and activists. As the second speaker in the opening plenary, Danny encouraged development organizations to “work themselves out of the job” of development and into the job of empowerment. He encouraged Northern and Western organizations to take a step back and allow Southern civil society organizations to take up the front lines of their own development. Media campaigns that put the voices of people from developing countries first are a critical step in doing this well.

Right now social media is mostly a fundraising and reporting tool of development NGOs and aid agencies. It’s just another way to “demonstrate results” and make appeals for financial support. But the power of social media remains in its ability to make the marginalized heard in their own voices. After listening to the appeals of speakers like Aya Chebbi, Alicia Robinson of WaterAid, and Jessica Horn— an activist, consultant and LSE alumna – I am more convinced than ever that development organizations need to stop trying to “be a voice” for poor and instead give the poor a microphone. Don’t show me a picture of someone impacted by your development project, re-tweet her feed, publish her videos, introduce me to the content she creates; be the conduit between her world and mine.

It has been the in-country human rights defenders that NGOs introduced to me that have told the most compelling stories of rights abuse in Bahrain, Myanmar, Pakistan and Egypt. Instead of Human Rights First simply telling me about the civil rights abuses in Bahrain, the organization directed me to Bahraini rights defender Maryam Alkhawaja by elevating her social media feed. This allowed other human rights defenders to track her return to Manama from exile—the world was watching the regime as her flight landed, as she passed through immigration, walked through the airport and into the arms of her family.

This is how the revolution is tweeted live. The Arab Spring is a name that outsiders gave the 2011 uprisings of the poor, disenfranchised and oppressed. Aya Chebbi said that Tunisians called it, “the revolution of dignity.” And dignity is not something that foreign development agencies or Western NGOs can give, or build, or donate. Yes, they can empower by training and funding and stepping out of the way. But dignity can only be restored to those deprived of it through their own agency. This was the message of campaigners and communicators at the Bond Conference: It’s time for the development industry hand over the microphone.

Really interesting article and agree that we need to change the way we communicate as a sector about the people we work with. Here is an example of this – Margaret from Uganda talks about campaigning for gender equality in Uganda – http://www.helpage.org/blogs/margaret-kabango-27548/why-i-will-never-stop-campaigning-for-gender-equality-985/