The ability to carry out free and fair elections faces an imminent threat, particularly in polarised electoral contexts. Latin America could place itself in the vanguard by exploring pilot schemes that monitor new digital trends and help to harmonise technology, democracy, and citizenship, writes Renata Ávila (Ciudadano Inteligente).

The ability to carry out free and fair elections faces an imminent threat, particularly in polarised electoral contexts. Latin America could place itself in the vanguard by exploring pilot schemes that monitor new digital trends and help to harmonise technology, democracy, and citizenship, writes Renata Ávila (Ciudadano Inteligente).

• Disponible también en español

• Também disponível em português

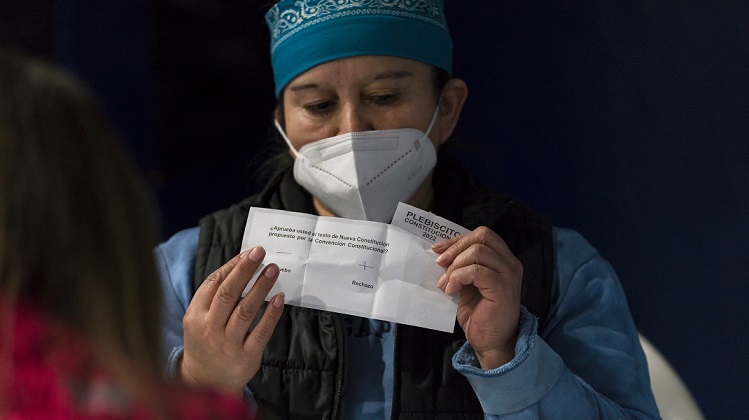

For elections to be free and fair they require transparency, equality, and honesty in campaigning, as well as access to information that enables voters both to make informed decisions at election time and to exercise oversight in-between elections. These foundations are set out in the Charter of the Organization of American States and act as a guide for electoral commissions and election observers.

However, the procedures and practices employed by these bodies are becoming increasingly ineffective in addressing the issues raised by modern-day election campaigns and processes, and in particular their digital dimension.

Faced with rapid techno-social change, election officials and observers have to rely on conservative, inflexible rules, drawn up from a classically positivist perspective: these rules leaves them with more questions than answers.

They are also deprived of the tools needed to perform the task of regulating and overseeing the processes which guarantee fair elections, rendering them powerless to deal with worrying digital trends that disrupt voter behaviour (Facebook’s influence being just one example).

Not just billboards, TV, and radio ads: the new campaign landscape

Monitoring and reporting on physical election campaigns is in itself no easy task, given problems of geographical access and hidden or undeclared expenses. Electoral authorities have drawn up clearly defined rules to control electoral expenses and prevent campaigning prior to official electoral periods, but these are only partially effective.

The picture becomes considerably more complicated when a campaign is digital, decentralised, and personalised. Nowadays, campaign development and investment to boost results is done ex ante. Parties or candidates that can afford to do so invest beforehand in sophisticated databases and political-marketing platforms that allow them to exploit social media much more effectively than their rivals.

Geolocation-based messaging, consumption profiles by geographic location, psychometric profiles which are skewed towards certain electoral pledges, age, social class, and habits – the most effective campaigns mobilise and transform all of this information to better target voters. Legal requirements on the reporting of related expenses is still very much a grey area.

The modelling of sophisticated data prior to and during an election campaign can be the crucial factor for parties operating in highly polarised political environments, where a one percent shift can prove decisive. Issues around privacy and the buying and selling of personal information are also at stake.

There have been repeated abuses in the compilation and analysis of large voter-related databases (or “big data”) in Latin America. The question arises as to whether we should insist upon greater coordination between data protection authorities (in those countries where they exist), human rights commissions, and electoral bodies such that political parties have to account in detail for all of the data and digital infrastructure used in campaigning. Such a requirement is increasingly necessary to ensure free and fair electoral contests.

Imbalances in access to campaign information

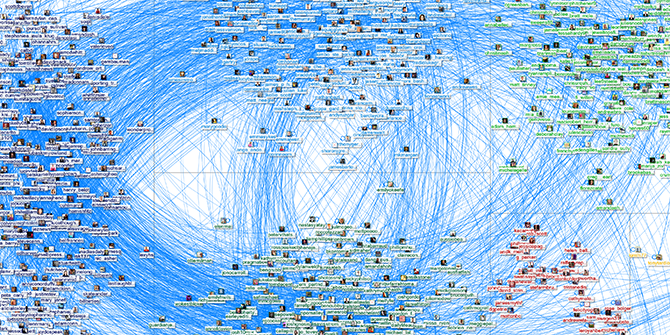

New technologies also pose a challenge to notions of transparency and unfettered access to information in election processes. A significant number of voters rely exclusively on social media to receive such information, but without understanding the logic or method of automatic filtering and curation carried out by digital platforms. The question becomes how to demonstrate or measure instances where a social-media algorithm gives greater prominence to certain content or a certain candidate.

Social media platforms are black boxes. Complex algorithms guide their behaviour, but since these algorithms are protected as trade secrets, they are not subject to old-style ethical or electoral rules that cover journalists and traditional forms of media. For example, there is no way of guaranteeing that they don’t violate prohibitions on distributing certain content before voting takes place, though this temporary restriction on the free circulation of information exists in electoral legislation throughout Latin America.

Given the ability of these platforms to generate messages which are segmented and targeted at certain audiences, voters effectively receive an election manifesto tailor-made to their preferences. Is this trend equally or more worrying than when radio and television airtime for political parties was distributed unequally? What are the ramifications for the informed voter?

While media bias and coverage of candidates can be measured objectively, the problem of monitoring how news is distributed and highlighted on social networks remains unresolved. Two voters with almost identical profiles consume media in very different ways, just as two very different people can have very different readings of the same political situations, as the Facebook Tracking Exposed project showed in the case of French elections. Is democratic dialogue possible if content does nothing more than reinforce our existing position and we close our ears to opposing views?

Suppression and manipulation of voters by anonymous external campaigns

In terms of the honesty of elections, there are a number of important factors to consider. These include “reverse censorship” arising from the torrent of misleading information on social networks as well as attacks carried out by political “bots”, the latter occurring frequently in Mexico and increasingly across the rest of Latin America.

There are an estimated 48 million bots on Twitter (and many others on Facebook) working to weaken critical voices, drown out legitimate demands, and practically wipe smaller parties off the social-network map.

The simplest and cheapest service in Latin America – whether for governments, opposition parties, or pressure groups – is provided by so-called “net centres”. These companies can be hired to promote political campaigns, defend the government of the day (as in the case of Guatemala), and even plan social media-based smear campaigns to amplify unfounded messages via social networks. Legitimate public discourse thus ends up buried beneath a tidal wave of misinformation, all in exchange for a paycheck. This is the reality of “online image management”.

The key issue here is how to address these growing problems while at the same time respecting the right to anonymity, freedom of expression, and provisions against prior censorship. When combined with the lack of accountability typical of private companies, respecting these rights can leave net centres impenetrable to scrutiny.

In addition, interference by parapolitical actors or foreign governments can take place in complete secrecy and at the behest of anyone with access to voters’ personal information and enough money to pay. Near-imperceptible interference is also enabled by two related factors: the access to sensitive data enjoyed by organisations such as the National Security Agency (NSA) through the PRISM programme revealed by Edward Snowden, and the close collaboration between companies like Facebook or Twitter and the Departments of State and Defence.

Further, the lax approach to cybersecurity of data authorities themselves means that even they lose millions of items of voter data every year. This combines with the growing data brokerage industry to increase the probability of cartels or parallel groups managing to exploit techniques of manipulation and swarm-based forecasting. It is likely that revelations about the activities of Cambridge Analytica are merely the tip of the iceberg. How can processes essential to democracy be safeguarded in this context?

A new era for election monitoring and new mechanisms for democratic participation

The ability to carry out free and fair elections faces a new and imminent threat, which is not specific to Latin America. This threat arises in polarised electoral contexts, and there are two possible courses of action in response.

Either we do nothing and risk sparking a crisis that undermines trust in electoral processes or we take immediate steps to identify and adopt best practices in this area.

Electoral missions can no longer ignore the need for oversight and vigilance when it comes to the use of new technologies, and neither can they be limited to superficial auditing of the electronic transmission of election results.

We are now dealing with more complex phenomena and actors that spill over national jurisdictions. Platforms controlled by the tech giants of Silicon Valley are at the heart of this, finding themselves confronted by questions which relate essentially to the public interest.

Creating a research lab on digital electoral practices

This article leaves many questions unanswered: given the lack of information and research on the subject, trying to answer these questions at this stage would be irresponsible and premature. Rather, these trends should be observed from a local perspective and analysed critically, while also bearing in mind the political, social, and cultural contexts of our countries.

Future elections in Latin America represent an opportunity to try out this kind of observation, to explore pilot schemes which monitor the trends discussed, and to place Latin America in the vanguard by harmonising technology, democracy, and citizenship with established structures of election monitoring. Together we need to identify emerging and recurring phenomena that abuse technologies new and old to undermine electoral processes.

By working closely with electoral authorities, election-monitoring bodies, and NGOs promoting digital rights, freedom of expression, privacy, and civic education we will be able to make informed proposals that can address rapid and ongoing changes in the nature of elections.

Identification and tracking of new practices will make it possible to trial different technical measures, public-policy solutions, electoral regulations, and privacy laws. This will allow us both to defend and to strengthen citizens’ rights. Now is the time to join forces.

To take part in this research lab, please get in touch via elecciones@digitalcolonialism.org

Notas:

• The opinions expressed here are of the authors and do not reflect the position of LSE

• This article is a translation of a piece published by Oficina Antivigilancia with a CC BY 3.0 licence

• Translated by Daragh Brady

• Featured image credit: Marcos Oliveira/Agência Senado, CC BY 2.0

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting