Lukas Cladders and Ursula Ferdinand share the story of world population specialist Robert René Kuczynski. He joined LSE in the 1930s after fleeing Nazi Germany, and became the first Reader in Demography in a British university in 1938.

Born in 1876 into a family of Jewish bankers in Berlin, Robert René Kuczynski studied economics and law in Freiburg and with the famous German economists Georg Friedrich Knapp in Strasbourg and Lujo Brentano in Munich. His work at the Statistical Office of Berlin under its director Richard Boeckh, the US Census Bureau, the Bureau of Labor Statistics in Washington DC, and as a statistician in the cities of Elberfeld and Schöneberg brought him into early contact with ideas on population development and the registration of life events. This experience also shaped his understanding of the statistician’s active role in social politics.

After the First World War Kuczynski was a leading figure in the Human Rights League and supporter of a German-French rapprochement. Between 1926 and 1932 he spent half the year in the USA, working for the Brookings Institution, a Washington based progressive think-tank. After publishing on wages, labour conditions and the consequences of American loans to Germany Kuczynski focused on population.

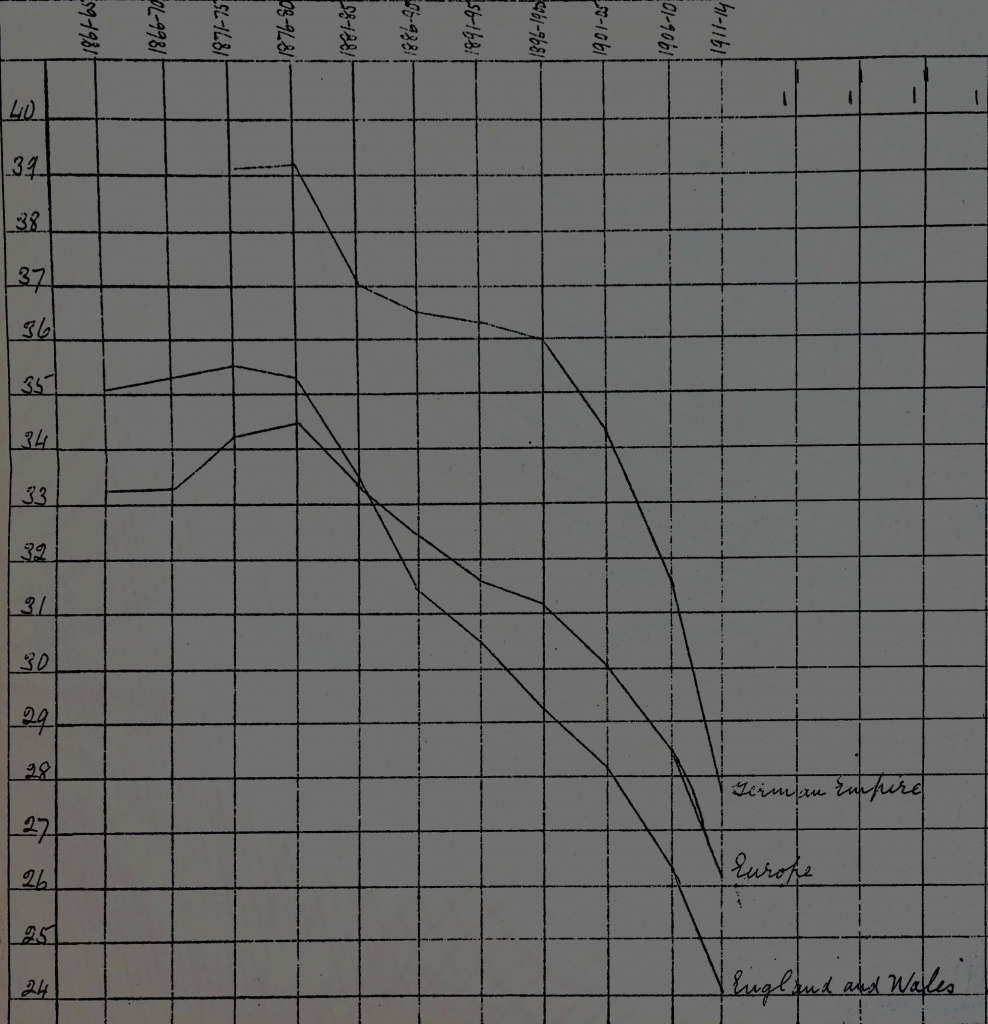

After the 1927 International Conference on World Population and the founding of the International Union for the Scientific Investigation of Population Problems (IUSIPP), the population quality and size was a subject of worldwide public and academic discussion. A year later Kuczynski’s international breakthrough came with the publication of The Balance of Births and Deaths, a two-volume compendium of data on birth-rate decline in Europe based on his model of the net-reproduction-rate. Kuczynski concluded that “the population in Western and Northern Europe is bound to die out” – though it would take centuries. Kuczynski’s methods were influenced by Political Arithmetick written by Sir William Petty which he described as “the cradle of demography”.

Kuczynski’s first contact with LSE was in February 1928 when he met William Beveridge on the initiative of the political scientist Graham Wallas, briefly a colleague at the Brookings Institution. Wallas described Kuczynski as working on “a really important book on population”. Beveridge had undertaken research on the declining birth-rate in the first half of the 1920s but by 1928 he wrote to Bernhard Mallet, head of the British Committee to the IUSIPP, that he was too busy with other projects to contribute to this research field. Interest in population development projections and the debate on the falling birth-rate grew in Britain in the early 1930s so it was a “lucky” coincidence that Kuczynski was one of the first German scientists to flee Nazi Germany to the UK in 1933.

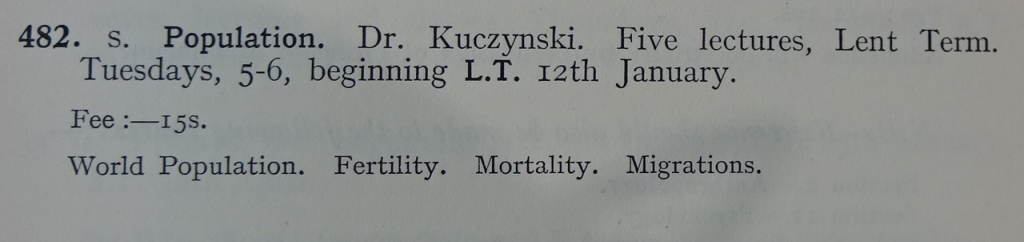

What Harold Laski described as a personal “tragedy”, in a letter to William Beveridge, led Kuczynski to London via Geneva and Northern France. Lancelot Hogben, then director of the short lived Department of Social Biology, backed the appointment of a demographic expert so Kuczynski received an LSE fellowship supported by the Academic Assistance Fund and the Rockefeller Foundation. The fellowship was renewed in the following years and Kuczynski’s demographic work moved onto methodological questions and the study of non-European populations while establishing the first population courses at LSE, entertaining an international network of population experts and developing close ties with the statistical organisation of the League of Nations.

In the mid-1930s LSE and the Eugenics Society joined forces to establish the Population Investigation Committee (PIC), an expert group to study population questions. When Alexander Morris Carr-Saunders, Head of the PIC, became LSE’s Director in 1937, Kuczynski was appointed the first Reader in Demography at a British university in 1938. He retired in 1941. While British researchers like Enid Charles or David Victor Glass, influenced by Kuczynski, focused on the reasons, consequences and remedies for the perceived population decline and engaged with all sorts of academic and societal actors, Kuczynski restricted his work mostly to questions of measurement. Although Kuczynski is a pivotal figure in our understanding of demography, he was often silent in public debates, engaging in quarrels with the Registrar General over the registration of vital events, the nation-wide census, the lack of colonial data and the need for trained personnel in population statistics.

Kuczynski’s final major contribution was in the field of colonial demography – as an adviser to the Colonial Office he was not interned and he produced an overview of the population in Britain’s colonies in his three volume Demographic Survey of the British Colonial Empire. After his death in 1947, his daughter Brigitte completed the publication of the last two volumes.

Today Kuczynski’s fame is eclipsed by two of his children: Jürgen became an important economist in the GDR and his daughter Ursula published a book about her spying activities for the USSR, undertaken partly in the UK. Meanwhile his demographic legacy is hidden – post 1945 theories of over population, the impact of economic development on birth and death rates and plans to restrict the non-European population through birth control programs did not fit with his cautious approach to large numbers and his support for free migration as a remedy to global economic problems.

What an interesting bio of a great man. To think that his work showed the dangers of population decline so long ago is incredible. Even today in 2021 people say the world is too overpopulated and we’re killing ourselves from climate change. Oh boy, if only they could see that we are lucky to have as many people as we do, chaotic though it may seem. Some countries aborted a whole generation of people and are only now understanding how important it is to have women have kids, lest their nation perish. This realization is perhaps too late because the allure of modern wealth for the working women is perhaps more attractive than giving birth.