The focus of LSE Library’s 2019 Michaelmas exhibition was the centenary of the appointment of one of the School’s most famous former Directors, William Beveridge. Beveridge’s time in charge (1919-1937) marked a period of significant change for the School, reflecting the broader turbulence of the 1920s and 30s, writes curator Inderbir Bhullar. The exhibition explored Beveridge’s time at LSE through the story of two schemes that he established: the Department of Social Biology and the Academic Assistance Council.

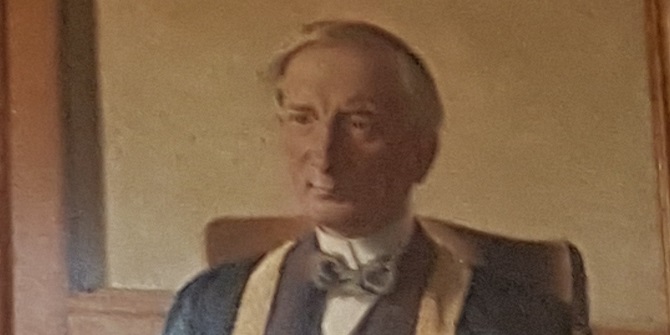

William Beveridge became LSE’s fourth Director in 1919 and, by the time he left in 1937, he had helped to reshape LSE into a world leading university. Sidney Webb, one of the School’s co-founders, described Beveridge’s time as a “second foundation”. It remains a fascinating part of LSE’s story that took place during a tumultuous period in history.

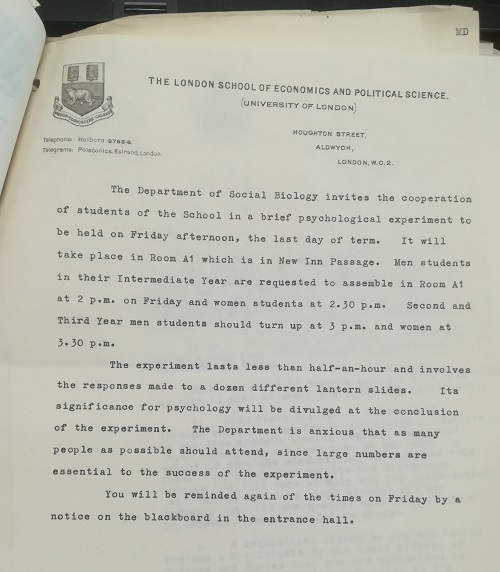

The exhibition’s first focus was Beveridge’s attempts to establish a Department of Social Biology. Beveridge was a eugenicist, like many of his intellectual contemporaries, and his firm belief in the empirical basis of the natural sciences led him to founding the department which it was hoped could lead to insights and bridge the gap between natural and social sciences.

In the second part of the exhibition we focused on Beveridge’s role in establishing the Academic Assistance Fund at LSE in 1933. The fund pooled donated money from teaching staff at the School to help support “non-Aryan”, predominantly Jewish, academics who were being expelled from teaching positions as the Nazi’s took power in Germany. The fund became the Academic Assistance Council, then the Society for the Protection of Science and Learning, and went on to help hundreds of people escape totalitarian regimes.

Beveridge and LSE

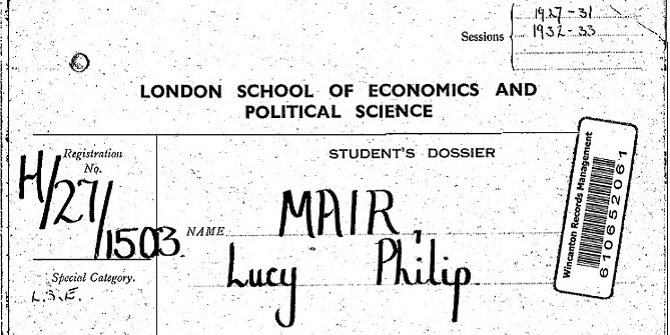

William Beveridge was appointed LSE’s Director on 1 October 1919 after holding numerous positions in public life. Whilst not formally an academic, he was a highly-regarded thinker who had made his reputation as an expert on unemployment. He had worked at Toynbee Hall, then been invited to be part of a committee on unemployment in London while also writing for the national newspaper The Morning Post. In 1909 he was made Director of Labour Exchanges, after convincing Winston Churchill, then a member of the governing Liberal Party, of their usefulness.

His work on social problems and unemployment brought him into the sphere of LSE co-founders Sidney and Beatrice Webb. He developed a close relationship with them and was invited to become Director by Sidney, whereupon he began the radical development of the School.

Eugenics

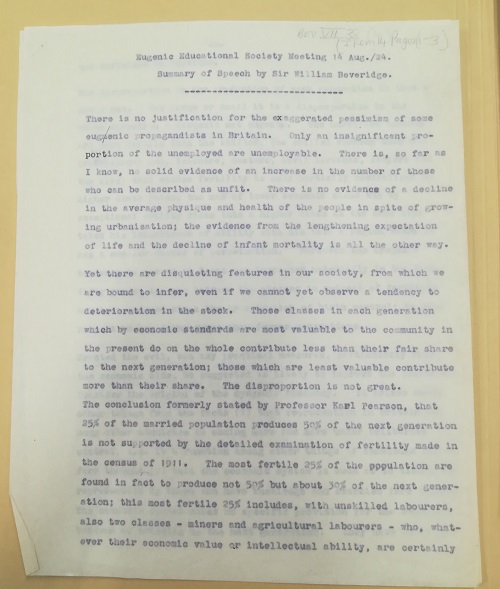

Beveridge and the Webbs, like many of their intellectual contemporaries, were eugenicists. Eugenics had been part of public discourse for many years, ever since Francis Galton had initially described it as “the science of improving [racial] stock” in the 1880s. The suggestion that an individual’s social position was due to genetically heritable characteristics and traits was shared by most eugenicists though opinions differed as to the amount of influence that environment played.

The idea was inevitably heavily culturally dependent and fed much discriminatory rhetoric and policy proposals, including forced sterilisation programmes for the “feeble minded”. Later the Nazi Party would use eugenic thought to underpin much of their racist ideology.

Beveridge became involved in debates on demographic issues. He argued against fellow eugenicists John Maynard Keynes, later Director of the Eugenics Society, and birth control pioneer Marie Stopes, over their fears of overpopulation.

Social Biology

LSE received significant funding from the US Rockefeller Foundation and Beveridge was a key fundraiser. Most of the money received was spent on teaching and research programmes.

The School’s curriculum already included modules which linked biology to the social sciences but Beveridge had hopes for a department dedicated to this course of study. In 1925 he wrote “The Natural Bases of the Social Sciences”, a proposal which outlined his thoughts and ideas for such a course.

Beveridge had long been interested in how methodologies from the natural sciences could help provide greater rigour and an empirical basis for the study of numerous social science topics, some of which were based on eugenics. Finally, with Rockefeller funding, he was able to open the Department of Social Biology in 1930.

Hogben saw little value in eugenic propaganda which he regarded as too limited and crude to be of much scientific value. He and his wife Enid Charles, a notable demographer, threw themselves into research work at LSE. However, he found that it became increasingly difficult to hire and keep research staff as they were being paid less than lecturers who had teaching responsibilities.

The department was also isolated as it was the only scientific centre in the School which led to further difficulties for Hogben, compounded by a reduction in funding from the Rockefeller Foundation. In 1937 Hogben left LSE to take up a Professorship at Aberdeen University and Beveridge left the School to take charge at New College, Oxford. Social Biology, with no Chair appointed and no champion remaining, finally closed.

Academic Assistance Council

In January 1933 Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany. In April the ruling Nazi Party passed the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service. The law made it legal to dismiss “non-Aryan” (predominantly Jewish) teachers, scientists and other government employees from their jobs.

William Beveridge and Lionel Robbins read about the first dismissal of academics while in Vienna. On his return, Beveridge initiated a rescue fund from contributions made by LSE academics, to aid those escaping Germany. The fund became the Academic Assistance Council (AAC), renamed in 1936 as the Society for the Protection of Science and Learning (SPSL). The organisation helped hundreds of academics find posts in universities all over the world.

Grim wartime realities meant that refugees were not always welcomed. At the 1938 Evian Conference, concerns over jobs and resources led to delegates from 32 countries voting to refuse entry to further German-Jewish refugees. In 1940 the UK government interned many German and Austrian nationals, including many academic refugees, over security concerns.

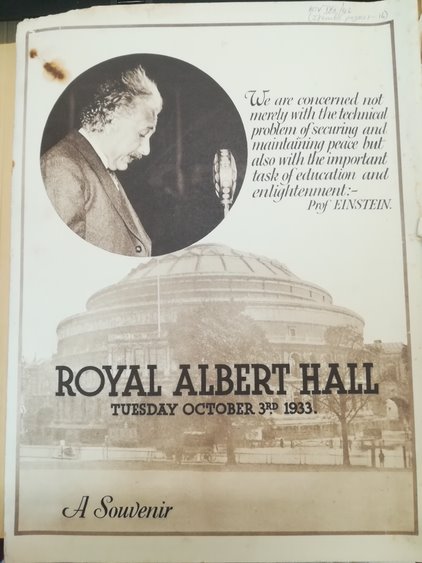

On 3 October 1933 Albert Einstein gave his final speech in Europe before departing for the safety of the USA. He spoke to encourage donations to the German Refugees Assistance Fund, a united body of four organisations that included the Academic Assistance Council. Alongside Einstein, the AAC assisted hundreds of other scholars, including those nearer to home such as Eduard Rosenbaum who was given a key role as LSE’s Acquisitions Librarian until his retirement in 1952.

William Beveridge also gave a speech to the ten thousand people who attended this Albert Hall meeting. The use of public events, the written word and broadcast media was crucial in raising not only money but awareness for the cause.

A lack of activity for the SPSL led to calls for its closure and reallocation of funds in early 1956. Beveridge remained on the Society’s board and resisted closure, pointing to the rise of totalitarianism in Hungary as reason enough to continue. The organisation remained operational and continues today as the Council for At Risk Academics.

Podcast and more

Listen to the podcast from Dr Chris Renwick’s 2019 talk William Beveridge and Social Biology at LSE

The exhibition The Power of Influence: William Beveridge as public intellectual and LSE Director was displayed at LSE Library between September and December 2019. Find out more about current exhibitions and events hosted by LSE Library

Reflections from the curator

I wanted to attempt to reflect more deeply on Beveridge’s time here and included topics that were sensitive and controversial rather than a simple chronological overview rehashing his achievements. I think it worked and I’m happy that the stories in the exhibition allowed us to reach out to others who have also been reflecting on the role of eugenics in British history. It also allowed us to show something more of the human side, warts and all, of one of the previous century’s key figures.

Posts about LSE Library explore the history of the Library, our archives and special collections.