Carys Lewis delves into the archive of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) held at LSE Library. WILPF members have campaigned for peace and justice since 1915 as this selection of stories from the archive demonstrate: campaigning for world disarmament after the First World War; the Great Peace Pilgrimage of 1926; and the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa.

About the archive

The Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) was formed in 1915 when over a thousand women representing European and North American countries met in The Hague to protest against the war raging across Europe. Today WILPF has active members across the world who share a vision for peace by non-violent means and promote justice for all. LSE Library received the first deposit of WILPF papers in 1973. A summary of the collection is here.

Campaigning for worldwide disarmament

Following the end of the First World War WILPF’s second congress was held in May 1919 in Zurich, Switzerland. This was the first time members of WILPF from opposing sides of the war had been able to meet since the 1915 congress in The Hague and the number of countries represented rose by four to 16. In Gertrude Bussey and Margaret Tims’ book Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, 1915 – 1965, a record of fifty years work there is a particularly touching description of how the war had affected some WILPated nations in the four years since the last meeting: “scarred and shrivelled by hunger and privation, they were scarcely recognisable.” Britain was represented by 25 members, covering a wide age span, some of whom are pictured below.

The Zurich congress saw WILPF pronounce the following statement on the Treaty of Versailles:

This International Congress of Women expresses its deep regret that the terms of peace proposed at Versailles should so seriously violate the principles upon which alone a just and lasting peace can be secured… The terms of peace… create all over Europe discords and animosities which can only lead to future wars.

As the Treaty of Versailles is now regarded as a key factor in the rise of the Nazis in Germany this statement is made all the more poignant. However there were some points in the Treaty which WILPF members did approve of including the disarmament of Germany as this picture demonstrates.

During the 1920s and 1930s WILPF actively campaigned for worldwide disarmament and ahead of the League of Nations World Disarmament Conference in 1932 WILPF circulated a world disarmament petition. It launched in May 1930 and by January 1931 33,000 signatures had been collected worldwide (including 10,000, nearly a third, from Wales) and shop fronts were taken over to promote the petition.

By the end of 1931 more than three million people had signed the petition. Britain provided the highest national total of over 1.5 million. By the time of the conference the final international total was six million. Members of the British section of WILPF travelled from London to Geneva. The signatures collected were transported in several boxes in crates and a big crowd gathered to see them off at Victoria station.

The Great Peace Pilgrimage of 1926

1926 is chiefly remembered for being the year of the General Strike which saw workers and Trade Unions across Great Britain fail in their fight for better working conditions as middle class volunteers united to maintain essential services. However there was another unifying event in 1926 which the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) played a key part in – The Great Peace Pilgrimage.

As part of WILPF’s campaign for universal disarmament sections from across the world undertook various activities in 1926 to spread this message to as many people as possible – however it was the British section that made the most spectacular demonstration for disarmament. In January 1926 WILPF set up a joint council to plan a nationwide ‘peace pilgrimage’ under the slogan of ‘Law not War’. The council consisted of 28 women’s and peace organisations that were united in their aim for a World Disarmament Conference to be held and for the British government to sign the Optional Clause of the International Court of Justice (which would accept jurisdiction in disputes of a legal nature).

In May, the same month as the General Strike, the Peace Pilgrimage set out along seven different routes from all corners of the country with the same end destination – London. During the journey a thousand meetings were held in towns and villages which the pilgrimage passed through, further spreading the message of peace. On June 18 the first contingent entered London and the next day the whole pilgrimage converged on four rallying points around Hyde Park before each set out in a procession for the final mass demonstration. An eye witness remembered events:

Here were women of the Guild House in blue cassocks and white collars, bearing their banners aloft; behind them walked members of the League of Nations Union, with bannerettes representing various countries of the world… there was a group of miners wives. At the head of each procession rode a woman in a Madonna blue cloak on a white horse.

The pilgrimage ended with a pageant in Hyde Park and from twenty two platforms speakers from all political parties supported the aims of the demonstration. Britain was united in the call for peace, special peace services were held in hundreds of churches and the press gave the pilgrimage significant coverage and commented favourably on it. However despite the significant support for peace demonstrated by the Pilgrimage it took six years for a World Disarmament Conference to be held.

WILPF, the anti-apartheid movement and Nelson Mandela

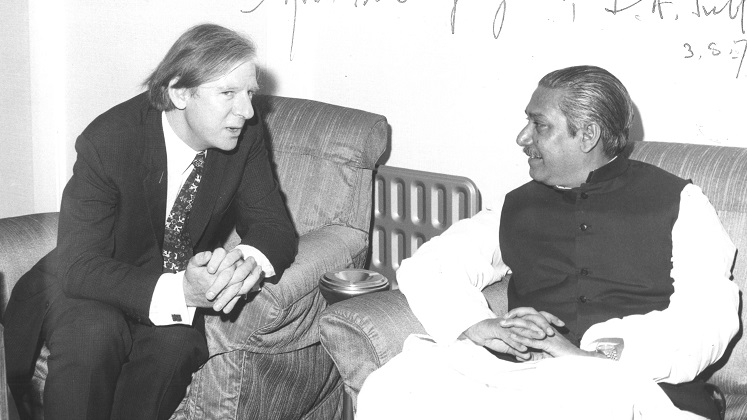

WILPF campaigns for the freedom of those whose human rights are being abused or who are living in undemocratic countries – both of which applied to apartheid South Africa. British WILPF members were informed on the situation in South Africa through regular updates in the publication Peace and Freedom. The October – December 1963 edition reports that London WILPF members had been given an account of life in South Africa by Leon Levy, the exiled white President of the South African Congress of Trade Unions. The article contains the following passage revealing the tensions in South Africa and what Levy thought could be done to stop it:

There was serious danger of a race war… since all methods of peaceful change were denied to Africans, and intervention by African states could not be ruled out… He believed that a rigorous boycott of South Africa and the imposition of sanctions could destroy the present regime.

The treatment of South Africa’s black population was a concern for WILPF members worldwide. WILPF’s headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland had its own publication, Pax et Libertas, which was distributed to members on a global scale and contains several articles highlighting inequality in South Africa.

In 1971 the British government began selling arms to South Africa despite the voluntary UN embargo on arms sales. WILPF was worried that the arms would be used against the black population and wrote to Conservative politicians in protest. The archive contains several replies many of which justify the government’s stance, one letter states the sale of arms would not be condoning apartheid but in the defense interests of Great Britain. WILPF continued to campaign against apartheid in the 1970s and 1980s with articles frequently appearing in its publications. In 1990 WILPF’s South Wales branch held a meeting on “Children and Apartheid”, which was reported on in Peace and Freedom. The article describes the violence inflicted on black South African children and the lively discussions on the changes needed before South Africa could be a free and just society. The article concluded with this:

The weekend after the meeting, Nelson Mandela was released, and already his appeals… have taken effect.

In 1994 South Africa held its first democratic elections when all races were allowed to vote, to observe this historic event six WILPF members travelled to South Africa. The June 1994 edition of Pax et Libertas contains the following observation of what the ability to vote meant:

The joy of people voting for the first time was palpable. Dancing and celebrations accompanied the feeling many people had that voting had helped them to become fully human.

On Nelson Mandela’s victory WILPF sent him a congratulatory message and wished the country success in building a new South Africa for all of its people.

This post originally appeared as a series on the LSE Library blog for the Swords into Ploughshares Project. The project was made possible by a grant from the National Cataloguing Grants Programme for Archives Fund.

Posts about LSE Library explore the history of the Library, our archives and special collections.

1 Comments