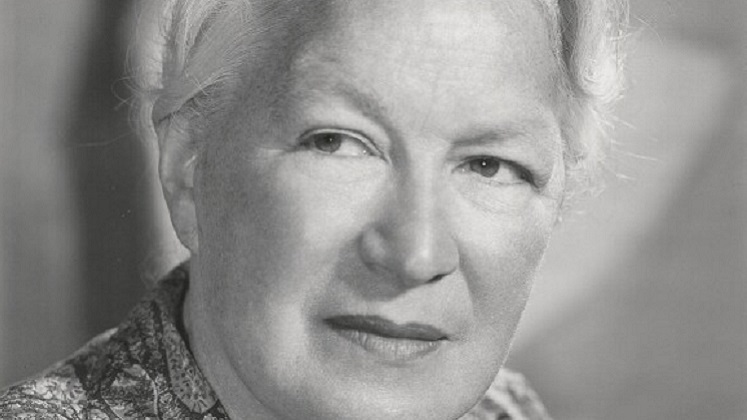

For someone who contributed so much to the life of his country, Richard Burdon or R B Haldane, remains one of the least remembered figures in modern British history, writes Professor Michael Cox. Often overlooked in favour of his altogether more controversial nephew J B S Haldane, a brilliant scientist, dedicated communist and alleged Soviet spy, “R B” has not so much been attacked for his views but rather put on the back burner of history where he has remained for years.

Few people have heard of R B Haldane today. If he is known at all, it is as an obese Edwardian politician who was sacked from the Cabinet for being pro-German in the First World War. [1]

Why have we not all heard of Richard, Viscount Haldane? The list of his achievements is extraordinarily long, yet beyond a blue plaque outside his home in Queen Anne’s Gate there is no memorial to him. [2]

As his most recent biographer has shown, [3] Haldane was a quite unique figure who aside from being offered a Chair in Philosophy (few if any British politicians have ever achieved that distinction) while declaring himself to be a follower of Hegel (perhaps another first amongst the British political class), also went on to transform the British Army in the years leading up to the First World War. He also did as much, if not more, for education than any other person in the early part of the twentieth century. As one of his many admirers has noted, even though Haldane never held a government position relating to education (indeed he turned one down after 1918) the “most significant aspect” of his life’s work “lay in this area”. [4]

The basic facts of his life can be found in his posthumously published autobiography. [5] Born in Scotland in 1856 and heir to a small estate in Perthshire owned by his devout father and equally religious, though perhaps less dogmatic mother, at the age of sixteen he was sent to the University of Edinburgh to study on the Arts Course. His parents then seemed set on sending him to Balliol College, Oxford, but as he himself describes it “they dreaded the Anglican Church atmosphere” there, [6] and so off the young man went to the famous University of Gottingen in Germany established back in 1734 by King George II of Great Britain, then Elector of Hanover too. Here, in an institution founded on Enlightenment principles where “scientific research was freed from censorship by the church”, Haldane discovered what he always found lacking in the ancient universities in England: a real “reverence for the personalities of the great teachers” and a genuine, almost painful search to discover the “ultimate nature of things”. [7]

Germany in effect became his inspiration and in time he became a fluent German speaker, a scholar of German thought – Goethe, Schopenhauer and Fichte were to become his heroes – and an avid admirer of most things German, especially its serious attitude towards the life of the mind combined with a dedication to applied scientific research.

He also discovered there something the British were only beginning to wake up to in the late Victorian era: that German industries were better organised, its workers better trained, and its education system years ahead of anything then existing in England. As he remarked in a later essay, Oxford and Cambridge were no doubt fine centres of classical learning, but the German universities were superior. They also managed to combine a reverence for high culture with a more systematic approach to the teaching of practical subjects. Their universities were not just better: they stood as indictments of what passed for higher education in England in the late 19th century. The lesson he drew from all this was very much the same as that drawn by the young Sidney Webb, born three years after Haldane, and like Haldane a great admirer of most things German: namely that unless Britain took active measures, and took them soon, it would in time lose its position at the top of the international league table. [8]

Haldane and Sidney Webb

I never belonged to the Fabian Society but was always very much in contact with Sidney Webb and I brought some of his ideas into the consultations I used to hold about the future of Liberalism.

R B Haldane [9]

Haldane returned from Gottingen to Scotland both physically and “mentally transformed” with his hair grown long and a renewed passion for research both into political economy (his first book was on Adam Smith) and German philosophy. But he was also a young man in a hurry and had two rather more down to earth goals in his sights: one was to secure a lucrative career in law in order to support both his political ambitions and lavish lifestyle, and the other was to enter politics, which he did as a Liberal MP in 1885.

Always regarded as a radical who sought to renew his party’s popular appeal by linking its future to the idea of empire and the cause of reform, Haldane first met Sidney Webb through the Fabian Society in 1887. Unlike Sidney, he never entertained the idea that socialism was the answer to the formidable challenges facing British society. In fact, so far apart did they seem that according to the Webbs’ biographer, at “first sight” it was “difficult to make out how they managed to cooperate” at all [10]. But Haldane’s brand of “new” liberalism and Sidney’s commitment to reform supported by serious empirical research made them natural partners.

It did not take long for the partnership to find a cause worth fighting for. Both great believers in the idea of efficiency and already actively engaged in politics, they found it relatively easy making common cause. Indeed, as early as 1890 Haldane was already proposing an alliance between progressives like himself and the Fabians like Sidney Webb to address what Sidney later called the great “education muddle”. Neither were opposed to universities teaching the classics to the few; however both tended to see education as a means to a much bigger end, and that end, as Sidney again insisted, was to maintain “our pre-eminent industrial position” by mobilising the untapped brain power and “brains of our young people”. [11]

Haldane could not have agreed more. As he argued in an essay penned in 1902, higher education was not just some add-on luxury but was the key to national prosperity. Foreign nations had already learned this lesson; it was now up to Britain to equip itself with the same “weapons”. [12]

Haldane and LSE

Amongst all our friends, R B Haldane takes precedence….

Beatrice Webb [13]

It was this belief in the power of knowledge which made Haldane an enthusiast for that great project launched in 1895: the “School of Economics and Political Science” where a new generation of students from the more “middling classes” would go on to learn about the modern, as opposed to the ancient, world. Haldane certainly proved himself to be a useful ally whose advice and support proved critical in what Beatrice Webb described as this “odd adventure”. [14] Nor was this adventure just about LSE alone. Indeed, if Haldane is to be believed, it was not just his support for the School which turned out to be important. According to his own account, he played the unlikely role of cupid in facilitating the Webbs’ engagement, when many of Beatrice’s friends and relations were warning against any kind of serious liaison with a well-known socialist whose cockney accent and lack of social graces made him quite unacceptable as a long-term partner! [15]

Haldane proved equally useful in other, perhaps more tangible, ways. Most obviously he deployed his not inconsiderable legal skills in making sure that the famous Hutchinson bequest designated to be employed for socialist purposes through the Fabian Society could be used – or according to critics, diverted – to help fund the School. Haldane also exploited his formidable establishment connections to get wealthy City people and financiers to back the new project.

Certainly, as a highly successful lawyer and member of Parliament with a who’s who diary to die for, Haldane was especially well placed to introduce the Webbs to those who mattered most and could help the School in its early formative years. Sidney and Beatrice certainly knew how to play that particular game. Sidney once observed that there were two thousand people in Britain one needed to know, and it was to them that one had to appeal. Finally, it was Haldane (yet again working with Sidney behind the scenes) who helped push through the reforms to the University of London which amongst other things created LSE as a recognised College within the University. This not only led to its teachers being granted full “academic recognition”; it also allowed the School to award the degrees of BSc (Econ) and DSc (Econ). [16] LSE had finally become a university in its own right.

Haldane’s vision for higher education went well beyond LSE, however. London after all was not merely the capital of the United Kingdom: it was the hub a great imperial order, and it was only right he believed that it should have a metropolitan university fit for purpose. As he put it, “The University of London ought to be the chief centre of learning for the entire empire”. However, if it was to be truly world class it had to have a unified, well-funded centre for scientific and technological research. Haldane drew lessons from what Germany had been doing and what it had achieved at the Technische Hochshule at Charlottenburg to which he made a “seminal visit” in 1901. It was he declared “by far the most perfect university I have ever seen”, and over the next few years with Sidney Webb acting as his “staff officer” moved heaven and earth to help create a British version of Charlottenburg in South Kensington, known by its more familiar name after 1907 as “Imperial College”. [17]

From Boer War to World War

Let us admit it fairly, as a business people should.

We have had no end of a lesson: it will do us no end of good.

The Lesson, Rudyard Kipling writing on the Boer War, 1901

Education with a serious purpose in mind also led Haldane to work with Sidney Webb on at least two other projects. Both organised through LSE, and both arising out of a serious concern about how to sustain Britain’s position at a time when its empire was facing a crisis of purpose. This was in part occasioned by the country’s less than brilliant (not to mention less than moral) performance in that most imperial, costly and divisive of ventures known as the Boer War, and in part by a genuine confusion about how to organise the empire in such a way as to maximise its role in increasingly challenging times.

One expression of this was the creation in 1902 (the same year the Boer War concluded) of what amounted to a “brains trust” at the School. Known as the “Co-Efficients” this brought together the Webbs, various liberal imperialists, three of its early Directors including Halford Mackinder, and the ever tireless Haldane at whose London apartment it held its first meeting. Regarded later as a failed attempt to set up a “think tank” with the objective – as H G Wells put it – “of discussing the Empire in a disinterested spirit”, the group managed to limp on for a few years before being wound up with a number of its more illustrious members complaining that however energetic Haldane had proven to be in helping launch the project, some of his interventions were far too steeped in “university and metaphysical German” to be of much practical value! [18]

The other, more successful experiment in which both Haldane and Mackinder were closely involved did a good deal better. The “Army Class”, as it was formally known, did not aim to address all the many problems facing the British army after the Boer War. What it did do however was deliver a “syllabus of officer education” that deployed the best of the School’s brains to get the officers who did attend to think more professionally about the role of a modern army. The leading academic light driving was Mackinder himself. But without Haldane’s encouragement as Secretary of War – he was appointed to the position in 1906 – not to mention his existing links to the School and the Webbs, there is every chance it might not have happened. Nor were the results of this extended engagement without some significance. As a distinguished civil servant later observed, by training “a whole school of military administrators” before 1914 (the Class finally closed down in 1932) LSE, with Haldane’s encouragement, “made the conduct” of the war a “conspicuous success, at any rate in the field of communication and supply”. [19]

Haldane’s efforts to reform the Army met with some success; indeed, Field Marshall Haig later claimed that he was the best Secretary of War Britain had ever had. But when the First World War finally broke out and quickly led to appalling losses on the western front, Haldane soon came under increasing attack from those looking for easy scapegoats to blame. They quickly found one in Haldane. His enthusiastic views about German achievements and German philosophy could in an earlier age easily be dismissed as the naïve ramblings of an academic idealist. In a time of total war when men were dying in their thousands fighting the “Hun” in a war for national survival his words could and were easily turned against him. They were also ruthlessly exploited by two newspapers – the Daily Express and the Daily MaiI and their powerful owners (Beaverbrook and Northcliffe) – each of whom was trying to prove that their paper was more patriotic than its rival. Haldane had never hidden the fact that he admired Germany; he had once even met and discussed international relations with the Kaiser. Sadly though the charge of disloyalty stuck, and Haldane was effectively thrown to the wolves, in spite of the fact that senior military figures agreed that if it had not been for his earlier reforms – most obviously his promotion of a British Expeditionary Force – “the allied cause” might well have been lost in 1914. But all to no avail. His friends in the Liberal party abandoned him, while his enemies who had always regarded him as being decidedly eccentric for having an interest in philosophy (and German philosophy at that) could only but crow over his downfall.

Education, education, education

In 1920, R B Haldane wrote:

I have lived in the cause of education perhaps more than in any other of the several causes I have been engaged in for many years.

Faced with a torrent of abuse Haldane responded in the same way as he had done in the past when faced with adversity: by looking forward rather than back. Nonetheless, he displayed a remarkable resilience, encouraged in large part by his good friends the Webbs. They continued to meet him on a weekly basis to discuss the changes all three would like to see once the war was over. Haldane was in no doubt where his priorities lay. As he told a friend, “he would now be able to devote himself entirely” to the issue of education, including worker’s education – a cause to which he was devoted like that other great stalwart of the School: R H Tawney. [20] Business education also interested him and it was LSE more than any other university which became the major beneficiary of this interest when “the largest proportion” of Ernst Cassell’s £500,000 Trust – of which Haldane also happened to be the Chair – went to support “no fewer than eight Cassell appointments at the School in the academic year 1920-1921”. [21]

Nor was his interest in the School just focused on utilitarian matters alone. Significantly, Haldane also went on to develop a close intellectual relationship with an academic who more than anybody else came to be seen as the socialist conscience of the School: Harold Laski. In fact, not only did Haldane encourage Laski to come to LSE – Haldane knew Laski’s Harvard colleague Wendell Holmes – but once he arrived in London in 1920 did all in his power to open as many doors as possible for the brilliant young radical whose reputation preceded him. The relationship between the two soon blossomed. Apparently the sixty-five-year-old Scot found Laski’s “intellect, wit and attention appealing”. More than that. Haldane was now a member of the Labour Party, moving gradually to the left and thus found discussions with Laski immensely stimulating. [22]

Finally, in 1924, Haldane at last achieved what had been denied him since his political downfall a few years earlier: membership of the Cabinet serving as the Labour government’s first Lord Chancellor. Even more satisfying perhaps he now found himself sitting across the table from his old friend Sidney Web (now Lord Passfield) who had been appointed President of the Board of Trade. As we know, the new government of which both Haldane and Sidney Webb were now members lasted only a few short months, brought down in large part by a “Red Scare” orchestrated by the Daily Mail just four days before the election in October.

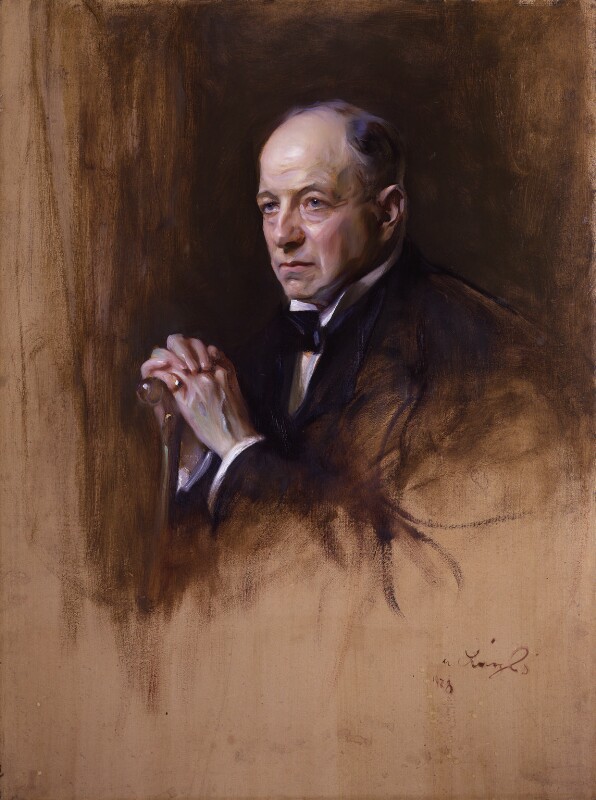

NPG 82171.

Once more Haldane found himself out of office; yet he still had a role to play, and for the next two to three years led the Labour Party in the Lords. Sadly though his health, which had never been robust (too much indulgence Beatrice felt), at last compelled him to leave public life just a short time before he died at his home in Scotland in 1928. As ever it was left to Beatrice – his most honest critic but most loyal of comrades – to sum up in her own inimitable words what Haldane had meant to the Webbs.

There were differences between them. No doubt about it she remarked. Nonetheless, in spite of this, he would for ever be remembered as our “oldest and most constant friend” who had shared with us a “common faith” and belief “in the application of science to human relations”. Not only did he have what she called an “almost fanatical faith in research”; he was compassionate too and felt the “sorrows and miseries of human beings” as well. He was in short a “noble and creative spirit”, someone who had made a difference to the world. [23]

He certainly had – both to a Britain whose system of education he had helped transform and to a School he had supported right from the start. Somewhat inaccurately referred to as one of the LSE’s co-founders, he might better, and more accurately, be remembered as the “great facilitator” of a great project whose purpose he had always understood and whose emergence from obscurity he had helped make possible. [24]

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Event

Haldane and LSE: applying political philosophy to public service in today’s polarised politics

5.30pm, Thursday 10 June 2021

References

Jane Ridley, “He Loved Germany Too Much”, Literary Review, July 2020.

Andrew Roberts, “Too much of a maverick”, The Critic, July-August 2020.

John Campbell, Haldane: The Forgotten Statesman who shaped Modern Britain, London, Hurst and Company, 2020.

Andrew Vincent, “German Philosophy and British Public Policy: Robert Burdon Haldane in Theory and Practice”, Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol 68, no1, January 2007.

Richard Burdon Haldane: An Autobiography, London, Hodder & Stoughton, 1929.

R B Haldane, Education and Empire: Addresses on Certain Topics of the Day, London, John Murray, 1902.

Royden J Harrison, The Life and Times of Beatrice and Sidney Webb 1858- 1905: The Formative Years, Houndmills, Macmillan Press.

A V Judges, “The Educational Influence of the Webbs”, British Journal of Educational Studies, Vol 10, no1, November 1961.

Beatrice Webb, Our Partnership, Longmans, Green and Co, 1948.

Ralf Dahrendorf, LSE: A History of the London School of Economics and Political Science, Oxford University Press, 1995.

Jill Pellew, “A Metropolitan University fit for Empire” History of Universities, Volume, XXV1/1, 2012.

G Sloan, “Haldane’s Mackindergarten: A Radical Experiment in British Military Education?” War in History, 2012.

Eric Ashby and Mary Anderson, Portrait of Haldane at Work on Education, London, Macmillan 1974.

Isaac Kramnick and Barry Sheerman, Harold Laski, A Life on the Left, London: Hamish Hamilton 1993.

Norman Mackenzie ed The Letters of Sidney and Beatrice Webb, Volume III, Pilgrimage, 1912- 1947, Cambridge University Press, 1978.

Footnotes

[1] Jane Ridley, “He Loved Germany Too Much”, Literary Review, July 2020.

[2] Andrew Roberts, “Too much of a maverick”, The Critic, July-August 2020.

[3] John Campbell, Haldane: The Forgotten Statesman who shaped Modern Britain, London, Hurst and Company, 2020.

[4] Andrew Vincent, “German Philosophy and British Public Policy: Robert Burdon Haldane in Theory and Practice”, Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 68, no1, January 2007, pp172-173.

[5] Richard Burdon Haldane: An Autobiography, London, Hodder & Stoughton, 1929.

[6] Ibid, p11.

[7] Ibid, pp17- 18.

[8] R B Haldane, Education and Empire: Addresses on Certain Topics of the Day, London, John Murray, 1902, esp pp1-39.

[9] Richard Burdon Haldane: An Autobiography, p114.

[10] Royden J Harrison, The Life and Times of Beatrice and Sidney Webb 1858- 1905:The Formative Years, Houndmills, Macmillan Press, pp297, 189.

[11] See A V Judges, “The Educational Influence of the Webbs”, British Journal of Educational Studies, Vol 10, no1, November 1961, pp33-48

[12] R B Haldane, Education and Empire, op cit. p30.

[13] Beatrice Webb, Our Partnership, Longmans, Green and Co, 1948, p97.

[14] Ibid, p84.

[15] Richard Burdon Haldane: An Autobiography, p118.

[16] Ralf Dahrendorf, LSE: A History of the London School of Economics and Political Science, Oxford University Press, 1995, pp56-57

[17] See Jill Pellew, “A Metropolitan University fit for Empire”, History of Universities, Volume, XXV1/1, 2012,

[18] Quoted in Ralf Dahrendorf, op. cit, p. 80.

[19] This section draws heavily from G. Sloan, ’Haldane’s Mackindergarten: A Radical Experiment in British Military Education?’ War in History, 2012, 19 (3). pp. 322-352

[20] Eric Ashby and Mary Anderson, Portrait of Haldane at Work on Education, London, Macmillan 1974., pp. 122-123.

[21] Ralf Dahrendorf, op. cit, p. 124.

[22] Isaac Kramnick and Barry Sheerman, Harold Laski, A Life on the Left, London: Hamish Hamilton,. 1993, pp. 162-168.

[23] Norman Mackenzie ed The Letters of Sidney and Beatrice Webb, Volume III, Pilgrimage, 1912- 1947, Cambridge University Press, 1978, pp. 302-303.

[24] Ralf Dahrendorf, op. cit, p. 25