Hungarian-born Karl Mannheim was exiled from Nazi Germany in 1933 and arrived in the UK, with help from the Academic Assistance Council, to be a lecturer at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). He taught at LSE and the University of London until his death in 1947, and is a key figure of classical sociology and founder of the sociology of knowledge. Terhi Rantanen, Professor of Global Media and Communications at LSE, asks why Karl Mannheim was never given a chair at LSE?

When I was doing research for my new book Dead Men’s Propaganda, using Karl Mannheim’s work, I read an article[1] arguing that at LSE Mannheim became a “kind of intellectual punching bag” and that many of his colleagues were “hellbent on ridding him from the School”. I became curious about Mannheim’s time at LSE, but unfortunately the task turned out to be difficult. The School archive turned out to be sparse[2], and the rest of materials concerning Mannheim are scattered in different places in- and outside the UK. However, one fact became clear and undeniable: Mannheim never received a chair at LSE. It was only in 1945 when the University of London appointed him as a full professor in the Institute of Education.

Why did LSE deny Mannheim a chair? He is widely considered a pioneer of classical sociology and sociology of knowledge. [3] Mannheim’s work was not only pioneering in the theoretical development of sociology of knowledge, but also in the concepts of ideology and utopia and of generation. As Louis Wirth wrote nearly 100 years ago, in his preface to Karl Mannheim’s Ideology and Utopia[4], that “we are witnessing not only a general distrust of the validity of ideas but of the motives of those who assert them”, and today this again rings true.

Mannheim’s career

Mannheim had the misfortune to be a doubly displaced refugee scholar, having been exiled from Hungary in 1919 and then from Germany in 1933. From 1930 to 1933 Mannheim served as a professor of sociology and political economy – in the celebrated “Frankfurt School” – at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University in Frankfurt am Main. He was among the first there to be stripped of his professorship and was forced into exile by the Nazis.

Mannheim was invited to LSE by Harold Laski and benefitted from the organised efforts of the Academic Assistance Council set up to rescue eminent scholars persecuted by the Nazis[5]. He was hired as a lecturer, teaching for example, a course on “Woman and Her Place in Society” in 1933 and his salary was jointly paid by the Rockefeller Foundation[6]. Even though already in the UK, Mannheim was on the Gestapo’s secret Sonderfahnungsliste (Black Book), compiled by the Gestapo and its informants, as an enemy of Germany, to be arrested after Germany’s invasion of the UK[7].

How did Mannheim experience LSE?

Mannheim was already used to criticism (if one ever is) in Germany when he was criticised by conservatives and Nazis for being influenced by Marx, and also by radicals for being insufficiently Marxist. His academic critics included Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Herbert Marcuse and Hannah Arendt.

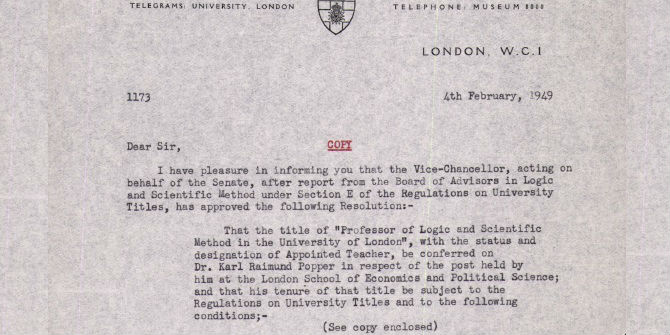

Mannheim’s forced migration to the UK was seen by him as a catastrophe and this view was shared by many UK sociologists. While at LSE he was further criticised by Karl Popper who is said to have had a “lasting rhetorical victory” over him, by Friedrich Hayek’s “ridicule” and Edward Shils’ “turn against” him[8].

Mannheim was very close to needing to leave the UK for the US after LSE warned him, in 1939, that his services were no longer needed. US colleagues tried to rescue him by offering him a US lecture tour, which he could not accept because of the UK’s immigration restrictions[9].

After Mannheim’s early supporters had left LSE, notably William Beveridge, Harold Laski and Bronislaw Malinowski, he lacked support under the new directorship of Alexander Carr-Saunders. Crucially, he had lost the support of his head of department, Morris Ginsberg, who may have felt that he stood in Mannheim’s shadow[10].

Just before Mannheim’s death (he suffered from heart problems) in London in 1947, he was offered a position as the first head of UNESCO’s European office.

His spouse, Dr Julia Mannheim-Láng, a psychoanalyst, expressed her anger with LSE by writing to Ernest Manheim[11], his cousin, in US after Mannheim’s death:

And when the Promised Land opened itself to him, he was tired, and his heart refused to go on. His murderer is this […][12] and this country, which can only take, but is incapable of giving back. How right Karl was to tell you to get away from here as soon as possible. Now they rack their brains and ponder who could give them only a share of what Karl used to give them [13].

Remembering Mannheim

Mannheim and Julia Mannheim-Láng were buried at Hoop Lane, Golders Green, Cemetery (see photo below) in London, and according to a staff member there, I was the first to want to see his monument for many decades. In this age of forced migration, would it be finally time to give Mannheim the recognition at LSE he was denied when alive?

Dead Men’s Tales: Ideology and Utopia in Comparative Communications Studies by Professor Terhi Rantanen was published by LSE Press in May 2024.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

References

[1] Pooley, Jefferson (2007) “Edward Shils’ Turn against Karl Mannheim: The Central European Connection”, The American Sociologist, vol 38, no 4, pp 364–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12108-007-9027-52.

[2] I thank Daniel Payne for his generous help.

[3] Mannheim, Karl (1929/1936) Ideology and Utopia: An Introduction to the Sociology of Knowledge. Translated by Louis Wirth and Edward Shils. UK: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

[4] Wirth, Louis (1936) “Preface”, in Mannheim, Karl Ideology and Utopia. An Introduction to the Sociology of Knowledge. Translated by Louis Wirth and Edward Shils, UK: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp xi–xii.

[5] Cox, Michael (2021) ‘“His Finest Hour”: William Beveridge and the Academic Assistance Council’. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/lsehistory/2021/04/28/his-finest-hour-william-beveridge-and-academic-assistance-council/.

[6] Timetable for Professor Mannheim on 26 May 1934. Salary. Professor Karl Mannheim. Part-time lecturer (no date). Karl Mannheim File. LSE Archive.

[7] Oldfield, Sybil (2022) The Black Book: The Britons on the Nazi Hit List, UK: Profile Books, pp. pp.3, 8, 269.

[8] See for example, Fuller, Steve (2006) The Philosophy of Science and Technology Studies, UK: Routledge, p. 19; Lassman, Peter (1992) ‘Responses to Fascism in Britain, 1930–1945. The Emergence of the Concept of Totalitarianism’, in Turner, Stephen P. and Käsler, Dirk (eds) Sociology Responds to Fascism, UK: Routledge, pp.214–40, p. 223; Sica, Alan (2010) ‘Merton, Mannheim, and the Sociology of Knowledge’, in Calhoun, Craig (ed.) Robert K. Merton: Sociology of Science and Sociology as Science, USA: Columbia University Press, pp.164–8, p.180.

[9] K Mannheim to L Wirth on 17 September 1939; L Wirth to B Malinowski on 31 October 1939; K Mannheim to L Wirth on 4 March 1940. Louis Wirth Papers. Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

[10] Woldring, Henk E S (1986) Karl Mannheim. The development of his thought: Philosophy, sociology and social ethics, With a detailed biography, New York: St Martin’s Press.

[11] Ernst Manheim’s (1900-2002) name was spelled differently. After his PhD at LSE, he emigrated to the US in 1937.

[12] Name removed.

[13] https://agso.uni-graz.at/archive/manheim/en/4_gb/index.htm.