A War for ‘Small Nations’

Completing my dissertation last May represented the culmination of a thoroughly inspiring, enjoyable, and introspective process, both academically and personally. I am very grateful to my supervisor, Professor Joanna Lewis, for guiding me through it, the History of Parliament Trust, for awarding it the winner of their 2022 Undergraduate Dissertation Competition, and the LSE International History department, for giving me an academic home for three years.

My dissertation, A War for ‘Small Nations’: Wales and Empire from the Boer War to the Great War, 1899-1918, examined the relationship that the re-emerging Welsh nation had with the British Empire at the turn of the 20th century, through analysis of local newspapers, speeches, personal correspondence, and Hansard records.

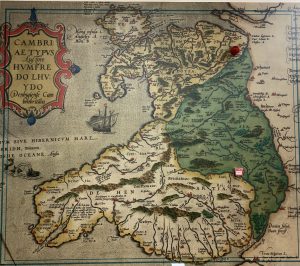

Wales is described by many as England’s first colony, yet it also played a formative role in British imperialism, creating a nuanced, almost paradoxical national identity.

Intwo of the most significant wars during this period, the 1899-1902 Boer War and the 1914-1918 First World War, the once-colonised Welsh nation compared itself to fellow ‘small nations’ facing colonial expansionism and defined itself against imperial aggression, both British and German.

It did this in contrasting ways. During the Boer War, a cadre of Welsh Liberal politicians used this rhetorical device to protest an otherwise popular imperial endeavour to conquer the Orange Free State and the Transvaal Republic.

In the First World War, the ‘small nations’ narrative was used to drum up Welsh support for the war, drawing an explicit link between Welsh history and the potential fate of Belgium, Serbia, and Montenegro. In this war, the narrative could be found throughout Welsh society.

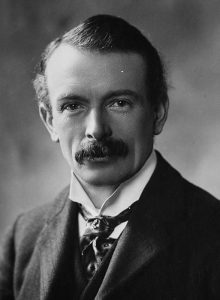

David Lloyd George, the first and only Welsh prime minister, was a particular exponent, personifying this narrative as one of the strongest critics of the Boer War, and one of the strongest supporters of fighting the First World War to the bitter end.

He was a Welsh speaker, who, early in his political career, campaigned for home rule

through the Cymru Fydd movement. By the end of it, however, he led the British Empire as it became the biggest in history. He was a complicated

man whose seemingly split personal and political identities mirrored those of Wales – Welsh, but also British. Colonised, but also a coloniser.

Wales’s place in history

Wales’s historical self-conceptualisation during the period occupied a liminal space. Elements of society would lament centuries-old English dominion while celebrating a multinational and inclusive Empire.

On the surface, this might seem inconsistent. But history is full of apparent contradictions. Wales’s own imperial relationship can only truly be understood by accommodating these seemingly paradoxical self-conceptualisations.

Doing so leads to the conclusion that the reason Welsh national identity was able to occupy this liminal space is largely due to how early it was conquered – 600 years before the peak of Empire, centuries before the emergence of modern nation states, before overseas colonialism, before scientific racism and the civilising mission.

While its development as a nation was well established by 1283 – it had a common language, culture, religion, and political traditions – it had not been able to stay unified under one banner for long, unlike its neighbour to the east. The real roots of Wales’s imperial relationship, in my opinion, stem from this aborted statehood.

Unlike the destruction of Wales’s political class, aspirations of self-rule, and legal independence, English monarchs did not sufficiently commit to the destruction of its language and culture, essentially absorbing a distinct nation into the English state, one that would then experience history joined at the hip with England as it unified with Scotland, conquered Ireland, and began turning its attention overseas, evolving over hundreds of years into the British Empire.

By the turn of the 20th century, Welsh language, culture, and religiosity were undergoing a renaissance, yet without its own institutions, its political and economic aspirations were inevitably bound with the success of Empire.

Modern Wales, therefore, had inherited two traditions. One as an ancient, proud cultural entity, and one as an integral member of the United Kingdom and the British Empire.

These two traditions can be seen in Welsh reactions to international events in the early 20th century, which was the focus of my dissertation. Elements of these traditions could be selected, exploited, and combined, to create a national narrative to suit political positions.

When protesting a war, one could appeal to Welsh grievances at being an unequal partner to England, to its peaceful, nonconformist religious tradition, or to its status as a once-conquered nation. But when supporting a war, one could equally draw from the legacy of victorious Welsh longbowmen at Crécy and Agincourt, from its role as the ‘engine of empire’, producing the steel and coal for Britain’s warships, and from its politicians’ often enthusiastic support for the imperial project.

A product of history

It is these concentric, overlapping layers of identity that are at the heart of the project. It confirmed to me that it is hard to understand contemporary Wales without understanding the layered nature of its historical, cultural, and linguistic traditions.

In fact, this was already something I understood, because like Lloyd George and Wales itself, my identity is split too. Both my grandmothers were born and raised in Wales and were fluent Welsh speakers, and both my grandfathers were born and raised in England.

I was born on one side of the border, in England, but spent the following 18 years on the other side, in Wales. My siblings and I spoke English at home, but Welsh at school.

My identity is part of that liminal story, a product of a long, complicated, and contested history, like, truthfully, all identities – none are isometric or historically isolated. But I wanted to understand that story, and this project was a part of that.

I was taught during my second year by the amazing Dr Rishika Yadav, who was a PhD candidate at the time and being supervised by Professor Joanna Lewis. Joanna was gracious enough to supervise me too, and it was incredibly fortunate that she was not only the foremost scholar of the British Empire at LSE, but also a Cymraes. Her assistance and wisdom was crucial and our meetings were a real highlight of my final year.

It was her idea that I enter the History of Parliament Undergraduate Dissertation Competition which A War for ‘Small Nations’ ended up winning, securing an award and a visit to the Houses of Parliament, so I cannot thank her enough for that, and for her guidance.

The process of completing my dissertation was an incredibly fulfilling experience, from spending whole days trawling digitised newspaper archives, to getting lost in Wikipedia rabbit holes, to visiting the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth on cold January days and trying to decipher handwritten letters, all to complete a piece of work that I’m incredibly proud of, and that really is a reflection of myself. I look back on it fondly.

Liminal Wales

Like my identity, Wales’s truth is lost somewhere in the middle. It is a mythical nation of the Mabinogion, of poetry and song, of stunning natural beauty, of ancient mountains, coastlines, and woodlands. Yet it is also a nation scarred by coal mining, transformed by the industrial revolution, that acted as the engine of empire, helping to drive forward a certain vision of progress that came at the expense of oppressing others.

It is a nation with the oldest living language in Britain, and one of the oldest in Europe, but that was not made an official language until 2011. Only around 18% of the population now speak Welsh, down from 90% in 1850. It is a nation proud of its unique heritage and culture, but one that largely rejects the idea of independence, with only around 20-30% of people supporting it.

National intricacies may be seemingly contradictory and difficult to summarise, but a flexible conceptualisation of identity allows strength through diversity. To decide that narratives and identities must fit into neat boxes ignores the rich complexity of history and is a sure route to national decline. My hope is that a fair, reasoned, and accepting understanding of our past can allow us to accept our mistakes and celebrate our successes, giving us a solid foundation to look forward to a better future.

In his typical bucolic prose, Lloyd George reminded us that while we can be proud of our nation and our heritage, we are all inescapably part of a much wider world:

The poetry of Wales was like the Severn, rising in the Welsh hills, deriving its source, deriving its inspiration, its impulse, from the mountains of Wales, overflowing into the plains of England, then winding back until now it forms a hitherto unbridged boundary between England and Wales at the very point where its waters are merging into the great ocean that laves the shores of many continents.

Source: Lloyd George, David, and F. L. Stevenson. 1918. The Great Crusade; extracts from speeches delivered during the war. Arranged by F.L. Stevenson. London: Hodder and Stoughton. Page 32.

Robert Stephen Crosby

23/5/23