Undercover, written by Guardian journalists Rob Evans and Paul Lewis, aims to reveal the truth about secret police operations – the emotional turmoil, the psychological challenges and the human cost of a lifetime of deception – and asks whether such tactics can ever be justified. An important account of police cover-ups, finds Tim Newburn, with heavy implications for public trust in the police.

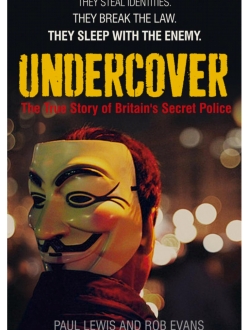

Undercover: The True Story of Britain’s Secret Police. Rob Evans and Paul Lewis. Faber and Faber. June 2013.

Undercover: The True Story of Britain’s Secret Police. Rob Evans and Paul Lewis. Faber and Faber. June 2013.

Half a century ago the phrase ‘the best police in the world’ was regularly uttered by politicians when referring to the British police. Hubris it may have been, but many believed it sincerely and the BBC’s long running police drama Dixon of Dock Green came to epitomise the imagined ideal: the always trustworthy, impartial and unarmed British bobby. In many ways it is no bad thing that we have relinquished such an unrealistically romanticised view of an institution that has powers as extensive as those of the police service. We should always be wary and judiciously critical of such an institution. However, the pendulum has swung very considerably indeed and some of the revelations of recent years – the conspiracy and cover-up over the Hillsborough stadium tragedy perhaps most of all – have seriously challenged public confidence in the police.

The latest episode, and one of the most shocking, is the result of the bravery of a whistleblower (how often are we saying that these days?) and dogged work by two investigative journalists from the Guardian newspaper. The story is one of undercover cops, tasked with infiltrating protest groups in order to gather ‘intelligence’. These officers belonged to something called the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS), part of Special Branch, which became something of a force within a force, as the book reveals, largely secret and generally unaccountable.

Established in the late 1960s, and eventually disbanded in 2008, the SDS’s focus was broad. Rather like the Special Branch that had spawned it, an initial concern with subversives – those considered a likely threat to the state – quickly expanded to incorporate a very wide range of political and protest groups: animal rights protesters, the anti-apartheid movement, the International Marxist Group, protesters at Greenham Common, the Socialist Workers Party, and the Anti-Nazi League among many others. What set the SDS apart was their core tactic: living the life of a protestor. SDS operatives gave up their warrant cards (their police identity), changed their names, grew their hair, changed their appearances and sought to establish personal relationships with their targets.

Whilst many of us, most perhaps, might accept that some level of subterfuge is necessary where the policing of very serious criminal activity is concerned, there is little in Rob Evans and Paul Lewis’s account that will strike most readers as even close to acceptable. The nature and consequences of the deceptions perpetrated are truly frightening. Indeed, the SDS’s informal motto – ‘By Any Means Necessary’ – seems all too close to the truth. Staggeringly, it seems to have tacitly understood that undercover officers (usually male) should target female protesters and form close personal – sexual – relationships with them. These relationships were by no means casual, in many cases becoming sufficiently serious and long-standing for the officer effectively to become the ‘partner’ of the person concerned. As such, these were no ordinary betrayals. They were, as one of the women pithily put it: ‘about a fictional character who was created by the state and funded by taxpayers’ money’.

Worse still, and at their most extreme, these relationships led to children being born. The officers not only deceived the women they formed relationships with, but they went as far as to father children that they knew they would have to abandon when, eventually, they were required to return to other duties. Though it is little commented on in Undercover, in many cases there were two sets of women (and their children) being deceived at the same time: the activist and the existing wife or partner. Can anyone in the police service seriously have thought this was justifiable? Given the lengths the officers were prepared to go, not surprisingly it appears few of their original marriages survived. Indeed, in one of the more bizarre episodes in the book one of the officers, Mark Cassidy, ended up in two sets of relationship counselling, simultaneously with each of the two women he was deceiving.

Then there are the targets themselves. Rarely do they appear to have been much of a threat, and increasingly it seems the SDS was simply targeting a range of organisations the police felt they needed more information about, including organisations campaigning around matters like police corruption. Shockingly, as those who have followed the news will know, Evans and Lewis discovered that among those being spied upon were the family of Stephen Lawrence, and that the purpose of the operation seems to have been to seek to undermine their case against the Metropolitan Police. What is still to be clarified is where the order to place the Lawrences under surveillance came from. How high up the Metropolitan Police hierarchy was this known? Yet another public inquiry seems increasingly likely.

SDS officers lied, cheated, and in some cases were involved in serious criminal activity. Their lying was by no means confined to those they were deceiving out ‘in the field’, but seems also to have extended to perjury. And much, if not most, of this appears to have occurred without a great deal of oversight from the senior officers at the Yard. Indeed, one wonders how much critical scrutiny any of these activities were placed under? Leaving aside the ethics for the time being, did no-one think about the costs? The financial implications were sizeable – for what gain? The human cost was enormous. Primarily, of course, to the women and children who found themselves caught up in these deceptions. But many officers paid a significant price too. Quite a number appear to have experienced significant mental health problems as a result of attempting to live two separate, but very different lives over many years. And finally there is the cost to the reputation of the police service. Just how great that proves to be we will simply have to wait and see.

————————————————

Tim Newburn is Professor of Criminology and Social Policy and Head of the Social Policy Department, London School of Economics. He is the author or editor of over 30 books, including: Handbook of Policing (Willan, 2008); Policy Transfer and Criminal Justice (with Jones, Open University Press, 2007); and, Criminology (Willan, 2008). He is currently writing an official history of post-war criminal justice, and was the LSE’s lead on its joint project with Guardian: Reading the Riots. He tweets at @TimNewburn. Read more reviews by Tim.

It’s decidedly GUBU, as they say in Ireland (grotesque, unbelievable, bizarre and unprecedented). The person whose account I’d really like to hear is an academic who was personally involved in all this (and who seemed like a thoroughly nice guy when I met him, in his current role). I can understand him wanting to keep his head down at the moment, but the questions aren’t going to go away – and it’s an extraordinary opportunity in research terms(!).