From the Classical Monstrous Races to the Elephant Man, Myra Hindley and Ted Bundy, the visualisation of monsters has always played a part in how society sees itself. But what is their function? This book seeks to investigate the human monster in Western culture, both historically and in our contemporary society, arguing that images of ‘real’ (rather than fictional) monsters help us both to identify and to interrogate what constitutes normality. Emily Colidge-Toker finds a potentially valuable resource for graduate students seeking a narrative for case study analysis.

Alexa Wright’s Monstrosity follows an uneven but interesting path through the history of the monstrous in the Western imagination. From imagined beings at the edges of the known world to spectres nestled within and likely inextricable from our society, Wright’s narrative describes the psychosocial cultural transformation of Western society and self through the evolution of its ‘monstrous other’. This grand narrative, though unevenly documented through visuals, could be (and in fact has been) further reinforced through literary analysis, making Wright’s contribution an appreciated new facet in our attempts to understand the transformations wrought through the processes of modernization. As Wright herself repeats in the book: “The visualisation of human monsters has always played a part in how society sees itself, helping us both to identify and to interrogate what constitutes normality.” Given her expertise in visual culture, and the relative dearth of material from the High Middle Ages, it’s understandable that the first few chapters are somewhat weaker than those dealing with 19th and 20th century mass murderers. Nevertheless, the contrast Wright establishes between early and modern manifestations of the monstrous provides great insight into the fears and insecurities of contemporary society.

Wright’s visual tour begins in the fourth century BC with the Monstrous Races, a collection of drawings believed to have been compiled from myths and misconceptions depicting vaguely humanoid creatures with either some exaggerated feature (my personal favourite: huge ears which function as wings, or a single gigantic foot which doubles as a sun shade for its desert-dwelling owner) or featuring some animalistic hybridity (such as a man’s body with the head of a dog, or the still-familiar satyr, a combination of man and goat). This and the subsequent chapters covering pre-modern periods, while presenting the occasional fascinating visual artefacts, failed in many instances to provide the necessary textual background to properly situate readers new to the subject, and interested parties are encouraged to have other sources (or the internet) on hand for any necessary clarification. The repeated references, for instance, to “localized social and moral instability” remain vague and unsubstantiated – but nevertheless instrumental in the existence and representation of the ‘monsters’ emerging before roughly the 1800s.

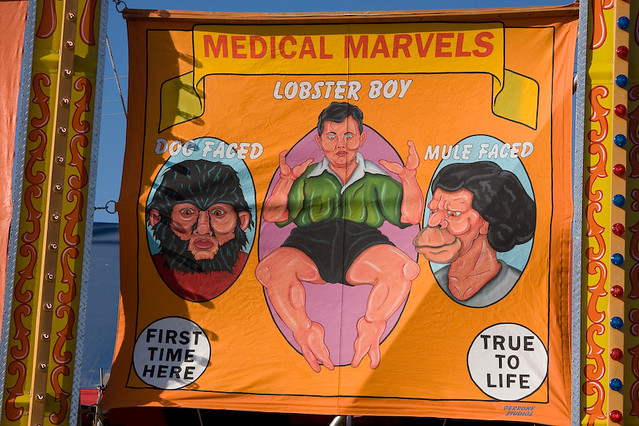

Chapter 4, the last of the weak chapters, deals with the representation, reception, and treatment of ‘freaks’ in traveling freak shows and carnivals, providing some really high-quality visuals (postcards and cartes de visite portraying the individuals in question) and a thorough history of these mediums and their social use, but the theoretical contribution to the narrative, like the refrain of “localized social and moral instability” from earlier chapters, is entirely unsubstantiated. The repeated assertion that freak shows were organized in such a way as to highlight their subjects’ ‘monstrousness’ and to reassure the audience that they are fully human “not-freaks” (p.84) is never reinforced with the research and historical analysis necessary to transform it from trite to properly fascinating.

However, the patient reader is well rewarded: although the first four chapters struggle to say anything theoretically interesting, from chapter 5 onwards Wright hits her stride. Beginning with an in-depth case study of Joseph Merrick “the Elephant Man”, she deftly guides the reader through “the transition from corporeal to behavioral monstrosity,” which she is careful to note “has not necessarily been straightforward or even complete, even within the formal domains of science and law” (p.104). Although the visual analysis consists only of a set of four nude medical photographs taken at the time of his admission to London Hospital in 1886 (p.117) and a carte de visite portrait in his “Sunday best” suit taken ca. 1887 (p.119), Wright is able to convincingly present the former, rather than the later, as the more respectful, ‘humaninzing’ of the representations. In the medical photos, despite his nudity, she argues that his deformities are fully integrated into those aspects of his body that were recognizably human, undeformed; he appears at ease and comfortable in his body. In the carte de visite photograph, on the other hand, the undeformed right side of Merrick’s face is hidden, emphasizing the growth enveloping the left side of his head. This is slightly undermined by an unpublished manuscript in which Merrick’s manager reports that Merrick “preferred to be exhibited in a freak show where he was paid, rather than ‘over there… [where he] was stripped naked, and felt like an animal in a cattle market'” (p.108). Nevertheless, at this point in the narrative arch we see a clear effort on the part of science to understand and make sense of the very corporeal ‘monstrousness’ presented in the first chapters, and to reinvest these ‘freaks’ with a certain degree of recognizable human feeling. She makes passing reference to Shelley’s Frankenstein and Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and I encourage the motivated student of literature or history to make off with these germinations of analysis and develop them further.

By the sixth chapter, Wright is making solid, interesting assertions in place of the meek suggestions of the earlier, less well-documented, chapters. It is at this point that she introduces the serial killers and other socially destructive individuals as the new, less easily set apart, incarnations of the monstrous, focusing on the still mysterious case of Jack the Ripper and the more well-documented case of Myra Hindley. In comparing the police sketches put together at the time of the murders attributed to Jack the Ripper to a digitally prepared composite produced by police for a 2006 documentary called Jack the Ripper’s Face Revealed, she convincingly argues first, that visualizing the monstrous remains crucial despite the shift from ‘corporeal to behavioural monstrosity’ we’ve been witness to over the course of the previous chapters, and secondly, that this visualization relies on a static image (Ted Bundy’s image never managed to become iconic in the way that Myra Hindley’s did) that is based heavily in the sociocultural constructs inherent in the scientifically disproven field of physiognomy, discussed at length in chapter 3.

Wright concludes with a compelling five and a half page discussion of the case of Anders Behring Breivik, the Norweigan mass murderer who made headlines in the summer of 2011 after bombing a government building in Oslo and then killing 69 young people attending a camp of the Workers’ Youth League of the Norwegian Labor Party. Emphasizing both his average (“normal”) appearance and the insecurities feeding his isolationist and heavily race-based politics, she notes that “his white skin and distinctly Nordic features align him with the nineteenth-century paradigm of a ‘superior Aryan race’ … With which he clearly identifies himself. If Breivik sees his appearance as a means of securing his own fragile identity, one feature in particular represents a tangible, corporeal, inscription of his fears” (p.159). Turns out, he had cosmetic surgery to Aryanize his Arabic nose… As Wright very succinctly notes, this kind of insecurity “reflects an anxiety about the relationship between self and cultural identity that is both personal to him and endemic in modern societies” (p.160).

It is this last note that holds the most resonance, and which proves both difficult to unravel and perhaps impossible to treat. Nevertheless, I encourage readers to give it a go. Despite the weak start, this book is a potentially valuable resource for graduate students seeking a narrative for case study analysis.

—————————————————————

Emily Coolidge-Toker is a recent graduate of Sabanci University’s Cultural Studies program. She received her BA in Sociology from Bryn Mawr College in 2007 and has been living and teaching in Istanbul, Turkey. Her research focuses on translation theory, mimesis, the globalization and politics of English, and diaspora studies. Read reviews by Emily.