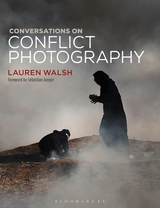

Conversations on Conflict Photography offers a fascinating series of dialogues between author Lauren Walsh and nineteen leading figures in the world of conflict photography, including photojournalists, digital editors and directors of photography around the world. Navigating complex issues with nuance and grace, and complemented by the visceral power of 110 photos, this is a profound and insightful collection that will encourage readers to reflect deeply on the questions it raises, writes Alessandro Ford.

Conversations on Conflict Photography. Lauren Walsh. Bloomsbury. 2019.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

We see it every day. From the front page of a broadsheet to the article we scroll past on Facebook. From the iconic and award-winning to the transitory and forgotten. Conflict photography is so embedded in the 21st-century news environment that its role in the world is rarely questioned. But what is that role? To shock, to propel into action, to inform, to bear witness? Depending on the answer, has that role been largely successful or unsuccessful during photography’s relatively brief history and how have dramatic changes in technology impacted it, from the first daguerreotype to the creation of the internet? Perhaps most pressingly, what are the political, social, psychological and moral implications of conflict imagery’s increasing proliferation and oversaturation within the globalised modern media?

These are but some of the penetrating questions explored in Professor Lauren Walsh’s Conversations on Conflict Photography, a profound collection of insights and reflections drawn from nineteen interviews with major photojournalists, digital editors and directors of photography around the world. The book’s genesis lies in a shocking question Walsh was once asked by a student of hers: why should I care and feel bad about a man starving in Sudan when I’m not responsible and there’s nothing I can do about it?

The question may seem monstrous, but deep down it is one that in some ways resonates with many of us. We likely wouldn’t articulate it in such a brusque manner, but the issue of our responsibilities to those who suffer, be they on the other side of the world or on the other side of the street, can be haunting. When this question posed to each interviewee, the answer is invariably interesting. There are those who categorically condemn the student and those of his ilk as apathetic isolationists, the less of whom is said the better. There are those who empathise with the student, identifying in his anger an understandable feeling of being overwhelmed that may be the inevitable byproduct of a globalised existence where we can daily witness the suffering of thousands, where we are more aware of the world’s horror than ever before and yet equally aware of our own extremely limited ability to change it. And there is everything in between.

The book’s title therefore yields several meanings. Conversations is a fascinating series of dialogues between Walsh and leading figures in the world of conflict photography, but it is also an attempt to talk indirectly to that student, as well as to the reader. What are our responsibilities, if any, as viewers? Walsh is well aware that there are no easy answers and remains sensitive throughout, navigating through marshy discussions with nuance and grace, never speaking of ‘will’ or ‘must’, but of ‘can’, ‘may’ and ‘might’. Nor does the book present any intellectual monolith. Views and positions obviously reoccur, but interviewees frequently disagree with one another on issues. The 110 photos included in the book have a visceral power and, combined with the accompanying text, make us stare deeper and longer than we usually would, noticing details that often go unseen.

Walsh attempts a more equal gender and regional balance than is present in the actual world of conflict photography, long the exclusive domain of white, swashbuckling scarf-wearing men, and ensures not only that traditionally marginalised voices are given space to speak, but also that the relations of power implicit in many images are themselves placed under the lens. Stereotypes and neo-colonial attitudes are dissected, from the classic visual trope of the ‘starving-African-child’ or the taboo on displaying dead bodies if they’re white, to the still prevalent practice of dispatching foreign photojournalists to ‘hot zones’ rather than using local photographers. That said, Walsh does aim Conversations at a Western, primarily American, audience.

In many ways, the book is also the story of an industry. Through the late twentieth century, the heyday of conflict photography, dozens if not hundreds of journalists and photographers would descend on each conflict and humanitarian crisis. Funding was plentiful, yet gatekeepers controlled the narratives, shaping stories in often cliched ways according to their perceptions of what audiences best respond to. The work of photojournalists from the Global South received little exposure and female practitioners were similarly disadvantaged.

The arrival of the digital age was seen by many as a democratising tool that would emancipate the camera-wielding witness, regardless of gender, ethnic or national identity. Yet this has proven only partly true, for though smartphones and the internet have indeed wrested power away from the traditional ‘gatekeepers’ of media (editors, directors, heads of content), they have also coincided with an explosion in the quantity of imagery in circulation. Some interviewees argue that the best photos will still rise to the top; others are more sceptical, noting the widespread desensitisation to shocking imagery mentioned above. Concurrently, these changes have led to dramatic cost-cutting across newsrooms. Foreign affairs desks have been particularly hard hit, and the dozens of photojournalists arriving at conflicts in years past is but a memory today. As one interviewee puts it when remembering her arrival in a conflict-affected area: ‘where is everyone?’

Several interviewees note how the result is that there’s no such thing as a pure ‘conflict photographer’ anymore, contributing to the proliferation of badly paid, dangerously inexperienced freelancers who, because of worldwide backlashes against a free press, now operate in environments increasingly hostile to journalists. In years past the first thing you’d do when arriving in a conflict zone was slap ‘TV’ in giant letters across all your equipment. Today such behaviour can be lethal. This danger is reflected in the growing arrests, attacks and killings of journalists around the world. It is also reflected in an increasing awareness of the psychological costs of covering conflict, as evidenced in the 2019 film A Private War, which documented the life of renowned war correspondent Marie Colvin (killed in Syria in 2012). Several interviewees reflect on how their work has psychologically affected them and, though none articulates it in these terms, what military psychiatrists call ‘moral injury’ likely plays a role. Their anguish is not just caused by having seen terrible things, but that having seen them, captured them and shared them with the world did not stop them from happening again.

Walsh ends Conversations with the thought that just as photography is a chemical process of light and darkness, so too is its fundamental purpose about light, about illuminating the truth and showing people events they wouldn’t otherwise see. What we as readers and viewers do with this knowledge is a personal choice, yet one that all of us would do well to consider.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Afghan women and children mourn the loss of family members who were killed in a raid by US Special Forces, near Jalalabad, Afghanistan on May 16, 2010. © Andrea Bruce/NOOR. Thank you to Bloomsbury for giving permission to use this image in the review.