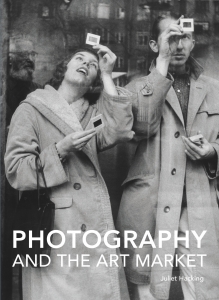

In Photography and the Art Market, Juliet Hacking combines business analysis of the art market with the historical emergence of the photograph as a collectable art object and a fundamental component of the international fine art scene. This is an essential handbook for students, curators and dealers, writes Vanessa Longden, as well as those wishing to enter the market as a private or institutional buyer.

Photography and the Art Market. Juliet Hacking. Lund Humphries. 2018.

The first of its kind to explain today’s art photography market, Photography and the Art Market, authored by Dr Juliet Hacking, combines business analysis of the art market with the historical context of the photograph as a collectable art object. This comprehensive account merges qualitative and quantitative methods to demystify the market and explores the structural elements—including galleries, museums, private collections and art fairs—which contributed to photography’s development from a leisurely pastime to becoming a fundamental component of the international fine art scene. Hacking’s publication is an essential handbook for students, curators and dealers, in addition to those who wish to enter the market as private or institutional buyers.

Many myths concerning the photographic art market continue to circulate. For instance, the notion that photographs fade over time; that they are easily faked or forged; and that prints are devalued by the issuing of more prints (which, Hacking assures us, is not the case). But one of the most prevalent misunderstandings is the perception that the market is difficult to navigate, despite becoming increasingly transparent and art photography becoming ‘a stellar investment in the last quarter of the twentieth century’ (77). To be clear, this book is not a step-by-step guide on how to navigate the market, but a collection of formations that need to be understood when fathoming the symbolic and economic value of the art object.

To demonstrate this, Hacking divides her publication into two parts. Part One, ‘Navigating the Market for Art Photography’, includes chapters on buying, keeping and selling photographs; analysing the market; and issues of authenticity and ethics. Hacking demonstrates the latter through various case studies, including appropriation in the work of Richard Prince and the legal battle over who owned the rights to Vivian Maier’s street photography after around 100,000 negatives were discovered in a lock-up following the artist’s death. Part Two considers how photography became art through a chronological account of photography’s development from its inception in 1839 through the Modern (1890-1940), the Photo Boom (1969-80) and Postmodernism (1981-99) to the Contemporary (the 2000s to the present day). This ambitious holistic approach is one of Hacking’s strengths. While the publication provides a broad overview of the history of photography, it remains comprehensible for a wide range of readers.

Chapter One, ‘Buyer Aware’, is a play on the Latin adage Caveat emptor, or ‘buyer beware’. To dispel any trepidation of entering the market, Hacking sections this chapter into a series of questions and answers, predicting some of the most commonly asked questions around photography as a legitimate investment. For the author, knowledge ‘should be acquired on a “need-to-know’’ basis’ (28). Readers can take heart in the fact that they do not need to be experts in the field to invest, but they are encouraged to start a dialogue with professionals, whether that is through auction houses or dealers. Other valuable advice includes always getting a receipt of purchase and checking the sellers’ terms and conditions. No two photographic prints are the same; each image has its unique context and provenance.

Consequently, what makes a photograph ‘valuable’ is increasingly unclear. Economic value is determined by symbolic value and vice versa. Similarly, no single art-world system (such as art market reports) or algorithm can predict the real or symbolic value of an image or the future trajectory of the market, but they can influence opinions and activities. As Hacking notes, ‘the process is cumulative’ (28), and that is undoubtedly part of its allure.

While photography is a relatively new medium, its art market is based on older models, such as painting and sculptures. It is uncommon to buy work directly from the photographer, but it is not impossible. Transactions are often managed by the dealer, who will also take a cut of the profit. Hacking advises purchasing artwork before it appears in a major exhibition and that the piece should be sold around the time of the show or thereafter. It is also worth considering other elements that affect acquisitions: buyers are advised to think about shipping costs and import taxes as well as whether to include a frame or not (it is cheaper to purchase a photograph without a frame). It is also worth considering the pitfalls of buying online, as many individuals are left disappointed with the quality of the photograph they receive. Before making a purchase, Hacking advises buyers to ‘immerse themselves in art photography to learn about colour, texture, tone and technique’ (59).

Similarly, there are many online resources and databases buyers can consult, which appear in the appendix of the book. In this situation, research is everything. As Hacking says: ‘You would not invest in the financial markets without doing a little research; the same is true for investing in art markets’ (67).

One of the most compelling aspects of Photography and the Art Market is its focus on emerging markets and future trends, covered in Chapter Six. Hacking’s main argument is that art and the art market are bound in a symbiotic relationship, as opposed to being two antithetical models (91). Emerging markets include Brazil, the Russian Federation, India and China (BRIC). Delhi’s Photo Festival launch in 2011 and Christie’s opening of premises in Mumbai in 2013 reinforced confidence in the growing market for art photography in India. Future trends include posthumously honoured artists who ‘sought a balance between the aesthetic and the conceptual’, such as Josef Sudek (1896–76), Christer Strömholm (1981–2002) and Francesca Woodman (1958–81) (100).

Investing in early career artists is also imperative to the market, with Juno Calypso being a prime example. Calypso took up photography in 2011, and her work has been exhibited internationally, with shows in New York, Canada and South Korea, among others. Just like Hacking, many viewers are drawn to Calypso’s The Honeymoon series for its wry sense of humour. The artist captures the pastel-coloured walls of American love hotels and transforms them into the backdrops on which she explores the sexual and societal frustrations surrounding the female body. For instance, A Dream in Green (2015) explores the notion of seduction and the falsity of perfection. Calypso stands, poised, in a pink heart-shaped bathtub surrounded by a series of rectangular mirrors. Calypso almost emulates the stance of Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (1485-86); her head tipped back, face shrouded by cascading red curls, she avoids the viewer’s gaze. But we also see so much of her, despite her back being turned. Strangely sculptural, like a Medusa-figure trapped in her own reflection, it appears Calypso also comments on the narcissism of selfie culture and the unrealistic expectations placed on women to ‘act’ feminine and fit a particular beauty standard. By posing nude but painting herself a mottled green shade, Calypso denies conventional spectatorship of her body, transforming the figure of the classical muse into an uncanny other. As Hacking notes, ‘Calypso is poised to receive more and more recognition’ since A Dream in Green has already appeared on the secondary market, and was sold well above its asking price (estimated at £5000–£7000, it sold at Phillips in London in May 2017 for £13,750) (101).

Photography and the Art Market successfully brings art photography and economics into dialogue. This publication makes the reader question how we speak about art and calls for a new model of analysis. ‘To understand how an art photograph will perform as an investment, you need to learn both about its history and about its place in today’s art-world system’ (221). By combining qualitative art-historical accounts with quantitative methods, Hacking recognises that the art market is not merely a financial entity, but a multifaceted one deserving of further exploration.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. Images are provided courtesy of Lund Humphries and should not be reproduced without the permission of the copyright holder.

Image Credit: Juno Calypso, A Dream in Green, from The Honeymoon Suite, 2015, archival pigment print, 99.8 x 150.7cm, private collection, taken from Photography and the Art Market by Juliet Hacking.

Find this book:

Find this book: