The collapse of socialism at the end of the twentieth century brought devastating changes to Mongolia. Economic shock therapy – an immediate liberalization of trade and privatization of publicly owned assets – quickly led to impoverishment, especially in rural parts of the country, where Tragic Spirits takes place. Following the travels of the nomadic Buryats, Manduhai Buyandelger tells a story not only of economic devastation but also a remarkable Buryat response to it – the revival of shamanic practices after decades of socialist suppression. Attributing their current misfortunes to returning ancestral spirits who are vengeful over being abandoned under socialism, the Buryats are now at once trying to appease their ancestors and recover the history of their people through shamanic practice. Buyandelger has created an emotive, accessible and well-researched ethnography sure to arouse sympathy and interest in readers, writes Michael Warren.

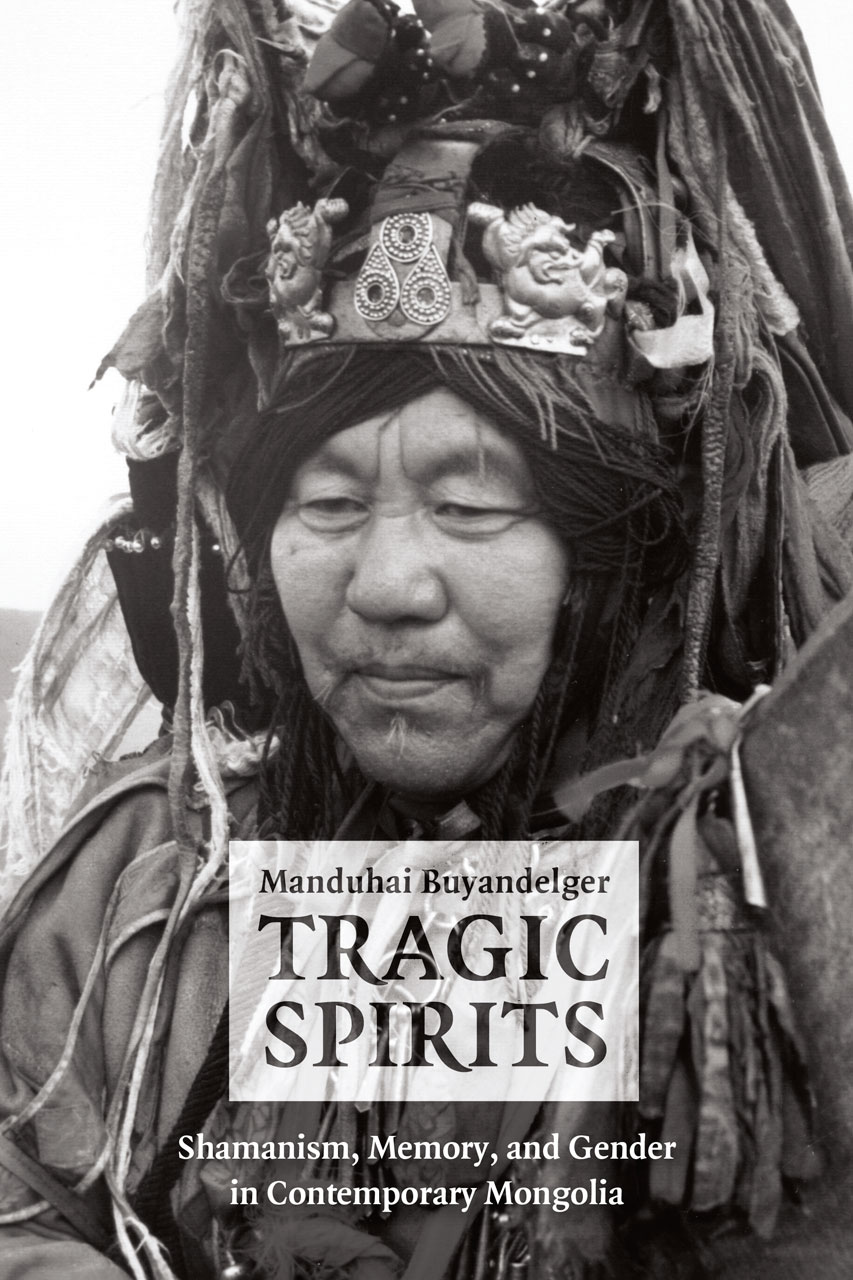

Tragic Spirits: Shamanism, Memory, and Gender in Contemporary Mongolia. Manduhai Buyandelger. University of Chicago Press. November 2013.

Tragic Spirits: Shamanism, Memory, and Gender in Contemporary Mongolia. Manduhai Buyandelger. University of Chicago Press. November 2013.

Manduhai Buyandelger’s Tragic Spirits: Shamanism, Memory, and Gender in Contemporary Mongolia is a compelling study of the nomadic Buryats’ response to sweeping changes after the fall of the USSR in 1991. Buyandelger is an associate professor of Anthropology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Tragic Spirits builds upon her previous studies of shamanism and its role within Mongolian society. Through the author’s encounters with her interviewees in north-eastern Mongolia, the book is packed with interwoven personal narratives which the author ties together to show the fragility and moulding of Buryat memory and Buryat shamanism’s purpose during the transition from state socialism to neo-liberal capitalism in Mongolia.

The Buryat nomads suffered a traumatising and turbulent twentieth century. They emigrated to Mongolia from Siberia in the early 1900s, only to endure persecution and continual marginalisation in the 1930s whilst Mongolia was a satellite state of the USSR. Under Mongolian socialism, religion was suppressed and mass executions occurred. The arrival of the market economy in 1990 did not bring the expected prosperity to Mongolians – although reforms lifted the lid on oppressive laws, economic havoc was wreaked: ‘the Soviet Union subsidized up to 30 per cent of Mongolia’s economy’ (p.113). Destitution became commonplace across Mongolia and discontent was prevalent amongst the Buryats. Many Buryats felt their misfortune was as a result of irate spirits of who had not been adequately propitiated for the previous 70 years (the spirits often emanated from those who had been killed by the state and had been improperly buried). Now operating openly, shamans (who act as mediums between people in the world in which we live and the spirit world) were and still are highly sought after by Buryat clients hoping to piece together the messages of the spirits that plague them. Once a message was pieced together, the spirit could be appeased.

It might be difficult for a Western rationalist reader to empathise with the Buryats’ prognosis of their problems, but Buyandelger accessibly shows shamanism’s positive perception amongst Buryats. Decades of state oppression and censorship brought the Buryat to the resort of more avidly seeking out shamanic help for issues of misfortune. Buyandelger importantly notes: ‘The Buryat’s engagement with shamanism is not a wilful illusion. For many people, the mere possibility of gaining knowledge that was different from the official state version, a chance to question and to encounter and deal with ambiguity, marked a break from socialism’s epistemic constraints’ (p.11). The author astutely observes that shamanism offered a raw and antagonistic alternative to the official state histories which perennially pronounced the wonders of successful revolution and modernisation – the history shamanism creates is ‘profoundly tragic’ (p.19). Much of the book is devoted to showing how shamanism can turn distant knowledge of a faraway past into touching individual memories for the client who hears the spirits speaking through the shaman – this is in stark contrast to the homogenizing and brutal control of knowledge by the state during socialism.

One of the many personal narratives to catch this reader’s eye is that of Baasan, in the final chapter of Tragic Spirits. Suffering a grave amount of misfortune, ranging from the sudden death of her brother to various bouts of serious illness such as seizures and tuberculosis, Baasan strives to meet many shamans and encounter countless spirits in order to discover her ancestry and rebuild her genealogy. Buyandelger relates this to medical anthropologist Arthur Kleinman’s argument (The Illness Narratives) that ‘the very act of making suffering meaningful helps a patient cope’ (p.266). Buyandelger’s analysis succinctly couples the personal with academic theory, which is an interesting difference to other studies of the Buryat, such as Rebecca Empson’s Harnessing Fortune, in which the academic analysis has greater stress than the human stories of the Buryat. One finishes reading Tragic Spirits knowing to the core that the fears and hopes of those whom Buyandelger met were studiously listened to.

Another notable personal account is the shaman Tömör’s story, detailed in Chapter Six, ‘Power and Persuasion’. From his story the reader learns of shamans’ dependency on gifts from their clients, strong social networks, and the importance of lineage in becoming a shaman. Tömör’s success and affluence as a shaman is juxtaposed with a later chapter in the book studying the struggles of female shamans, in particular Chimeg. The exploration of gender in shamanism is one of the most insightful sections of Tragic Spirits. The author reveals the challenges posed by Buryat patriarchy to female progression into the shamanic profession, which only grew tougher with the demise of socialism. Buyandelger points out that ‘with the dissolution of the state farm, a relatively gender-equal employment system also ended, production shifted from the state to the domestic sphere’ (p.192). Increasing importance of the domestic sphere meant growing difficulties for female shamans such as Chimeg who as a single woman did not ‘fit the female gender norms of virtuousness’ (p.194) and aroused suspicion on their journeys. Being single allowed Chimeg the opportunity to travel far (which would not have been possible in marriage), however she was stigmatised and limited in clients due to her marital status.

The major strength of the book lies in the vivid sense of identity which comes from the personal accounts of Buyandelger’s interviewees; this is complimented by the author’s nuanced theoretical analysis. There are brief insertions of comparable examples of global practices of shamanism in the late twentieth century (Indonesia, Niger and Mali) but not enough to create a full comparative study with the Buryats – which would be useful to create a more rounded perspective of the Buryats. The book is an excellent addition to studies in the area, such as Morton Axel Pederson’s Not Quite Shamans: Spirit Worlds and Political Lives in Northern Mongolia and Michael Taussig’s Shamanism, Colonialism and the Wild Man: A Study in Terror and Healing. Buyandelger has created an emotive, accessible and well-researched ethnography sure to arouse sympathy and interest in readers.

————————————————-

Michael Warren completed an MSc in Empires, Colonialism and Globalisation at the LSE in 2012, having graduated from the University of Sheffield (studying on exchange at the University of Waterloo, Ontario) with a BA in Modern History in 2011. He has researched as part of an open data project for Deloitte and the Open Data Institute, and worked for the All-Party Parliamentary Health Group. He is an Analyst at Accenture. Read more reviews by Michael.