This is a timely moment to be getting to grips with Chile. With the fortieth anniversary of the 1973 coup just passed and the twenty-fifth anniversary of the return to democratic governance next year, Chileans are asking important questions about their constitution, environment, and socio-economic model. The Chile Reader is a highly recommended, illuminating, and thought-provoking read, featuring interviews, travel diaries, letters, diplomatic cables, cartoons, photographs, and song lyrics. Tanya Harmer recommends this collection to students wanting to gain a clear understanding of issues that are being debated in the country today.

The Chile Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Elizabeth Quay Hutchison, Thomas Miller Klubock, Nara B. Milanich and Peter Winn (eds). Duke University Press. 2014.

The Chile Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Elizabeth Quay Hutchison, Thomas Miller Klubock, Nara B. Milanich and Peter Winn (eds). Duke University Press. 2014.

For those who have never visited Chile or do not know a great deal about the country, this Reader is an impressive and accessible introduction to it. The editors and all those that have translated documents offer a thoughtful window onto Chile’s history, culture and politics. Through written texts, photographs of archaeological ruins, art, poetry, song lyrics, and transcribed interviews spanning over 500 years, the reader is immersed in the complexities of the country and given the opportunity to navigate between the constructed myths and realities that shape Chile today. There are obvious recognisable voices in the volume, such as Pablo Neruda’s prize-winning poetry and that of Chile’s democratically elected ex-president, Salvador Allende, who sought to lead his country along a peaceful democratic road to socialism before a military coup toppled his government on 11 September 1973. However, these are contextualised within a rich tapestry of diverse perspectives that capture the nation’s multi-layered and distinctive character; we hear from Spanish colonial elites, conservationists, clergy, workers, landowners, miners, peasants, politicians, economists, lawyers and human rights activists. The result is a full and rounded picture of Chile’s past, present, and future that provides those new to the country with tools to recognise and understand it.

For those who are more familiar with Chile, there is also a lot to reflect on and rethink in a new light. They will recognise the mountains, the earthquakes, the inequality, the Mapuche’s long standing struggle for recognition and land, the legacies of colonialism, Santiago’s pollution and the country’s peculiar mix of authoritarianism and democracy, conservatism and radicalism. But what is particularly useful about this latest volume from Duke University Press’ Latin America Reader Series is that these features of Chile’s history, culture, and politics are laid out side by side in a way that encourages us to examine the linkages between them. The inherent contradictions that exist within Chile that are prominent in this volume also challenge preconceived stereotypes or generalizations. Through primary documents, we explore Chile’s bountiful yet tragic landscape, its promising yet destructive modernization process, and tensions between its isolation and interaction with the outside world.

The recurring nature of themes that have underpinned Chilean history and society are brought to light clearly and effectively in the choice of documents. Together, they challenge us to think in broad terms about continuities and long-term trajectories. As the editors state in their introduction, their document selection is “neither comprehensive nor exhaustive” but it is specifically designed to “speak to themes such as democracy, social inequality, economic development, the environment, and ethnicity”. The “persistent narrative of Chilean exceptionalism” within a Latin American context and what it meant to different Chileans to be Chilean are particularly prominent themes explored through the documents. Another is the search for and questioning of “modernity” in Chile – along with its “recurring nemesis, socioeconomic inequality” (p.3). Ultimately, no single vision or portrayal is put forward. As the editors state, they want readers to have the tools to “judge for themselves” (p.8). But the questions that frame volume are enormously helpful in directing the reader’s attention to important ideas and concepts that define Chile.

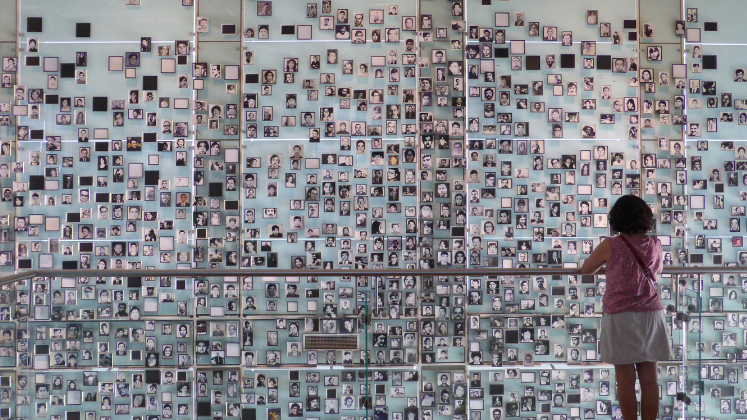

The Chile Reader will have a very practical purpose for students of Chilean and Latin American history in providing them with direct access to Chilean perspectives that not always easily accessible in academic monographs and articles. With helpful introductions to each document and chapter, the volume begins by looking at Chile’s environment and landscape before moving chronologically on to examine indigenous peoples, conquest, and colonial society; early independence and nation building; the growth of export led trade and the “social question” in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; depression, development, and the “politics of compromise” from the 1920s onwards; reform, revolution, and Chile’s thwarted road to socialism; the Pinochet dictatorship, military rule, and neoliberal economics; and the return to democracy.

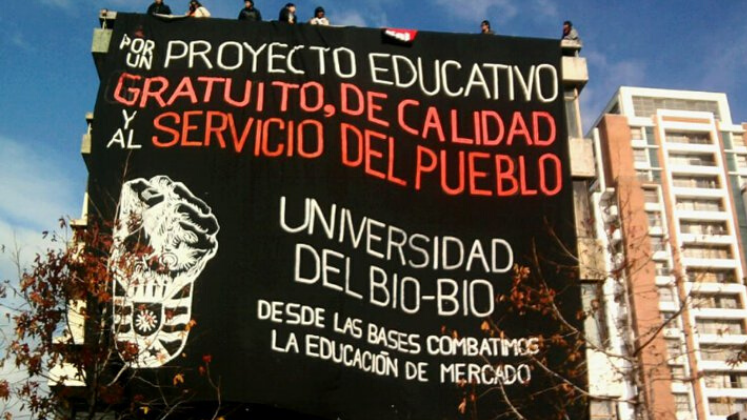

This is a timely moment to be getting to grips with Chile. With the fortieth anniversary of the 1973 coup just passed and the twentieth-fifth anniversary of the return to democratic governance next year, Chileans are asking important questions about their constitution, environment and socio-economic model. Earthquakes and natural disasters have recently bedevilled the country and the consequences of mining are becoming ever more pressing. There has also been a surge in the level of social mobilisation throughout the country in recent years led by students, workers, environmentalists, and Mapuche communities. And for anyone wanting to comprehend these phenomena and the choices that are being debated in the country today, an understanding of its past is imperative. In this respect, The Chile Reader is a highly recommended, illuminating and thought-provoking read.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image Credit: Images from a protest against the funeral of Augusto Pinochet, dictator of Chile between 1973 and 1990. The poster on the left reads “You cannot honour a murderer”, followed by one of Pinochet’s most famous quotes: “Lies are discovered through the eyes, and I lied often”. Credit: santiago chile CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.