In Resisting Neoliberal Capitalism in Chile, Juan Pablo Rodríguez examines two recent social movements leading the social and political contestation against neoliberalism in Chile, not only showing how these embody critique in practice, but also drawing on these experiences to interrogate the very idea of social critique. This ambitious book is a welcome contribution to a sociology of social movements grounded in a reflexive dialogue between critical theory, social movement studies and empirical enquiry, writes Malik Fercovic.

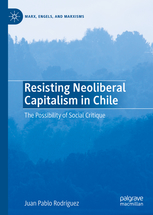

Resisting Neoliberal Capitalism in Chile: The Possibility of Social Critique. Juan Pablo Rodríguez. Palgrave Macmillan. 2020.

Beginning on 18 October 2019, Chilean society has experienced its most dramatic wave of social unrest since the end of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship 30 years ago. What at first begun as a secondary school student protest rejecting a hike in metro fares in the capital city, Santiago, rapidly turned into a nationwide popular revolt against Sebastián Piñera’s right-wing government and the neoliberal arrangement imposed by the dictatorship almost five decades ago.

Beginning on 18 October 2019, Chilean society has experienced its most dramatic wave of social unrest since the end of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship 30 years ago. What at first begun as a secondary school student protest rejecting a hike in metro fares in the capital city, Santiago, rapidly turned into a nationwide popular revolt against Sebastián Piñera’s right-wing government and the neoliberal arrangement imposed by the dictatorship almost five decades ago.

This sudden, vast and powerful expression of social discontent came as a shocking surprise for many observers accustomed to seeing in Chile the most prosperous and stable Latin American nation in a region historically lacking in both. Indeed, until mid-October, mainstream analysts, from both within and outside of the country, underlined Chile’s substantial economic growth, educational expansion, access to mass consumption, increasing wages and low levels of corruption in recent decades. Only days before the start of what is now known as the ‘Chilean awakening’, President Piñera, insisting on Chile’s success story, declared the country to look ‘like an oasis’ in a troubled Latin America.

But, of course, this conventional depiction offers a very incomplete portrait of Chile. It obscures the hidden stratifications and intricacies of a rapidly changing social structure, the diffuse but unmistakable presence of a widespread discontent beneath the pacified surface of a consumer society, the mounting negative perception of high levels of inequality, as well as the sporadic impulses and periodic turbulence of social movements slowly but steadily gathering force—e.g. the secondary school student (‘penguin’) rebellion in 2006, the massive university student protests in 2011, manifold socio-environmental conflicts across the country, a robust contestation of Chile’s pension system in 2017 and a powerful feminist movement in 2018. Even a hasty glimpse at these diverse expressions of discontent might well have prevented the surprise many observers have experienced over the past months.

As an expanding literature suggests, the successive waves of social and political contestation unsettling the consensus on which the post-dictatorship Chile has been built cannot be doubted. But how do these variegated expressions of discontent articulate and practise their critical voices?

This somewhat neglected yet key question is at the heart of Juan Pablo Rodríguez’s Resisting Neoliberal Capitalism in Chile: The Possibility of Social Critique. In this book, Rodríguez studies two of the main social movements leading the social and political contestation against neoliberalism in recent years: namely, the practices of social critique of low-income urban citizens known as pobladores and the nationwide student movement in 2011 against unequal higher education. In addition to being part of longstanding social struggles throughout Chile’s history, according to Rodríguez, these social movements deserve our special attention for two complementary reasons. Rooted in the heavy burden of household and student debt, pobladores and the student movements embody the first successful endeavours to resist the ‘logic of fragmentation of neoliberalism’ in contemporary Chile. And they have managed to galvanise a larger critique not just of specific issues—the right to the city for poor city-dwellers or free and public-based higher education—but of Chilean society as a whole.

Yet Resisting Neoliberal Capitalism in Chile has more ambitious goals. Rodríguez’s book not only examines the way these two social movements embody critique in practice against neoliberalism in Chile. Taking the ‘return of Marx’ as a major pointer of the renewal of social critique over the past decade, he also inspects these experiences of social and political contestation to interrogate the very idea of social critique developed by diverse contemporary critical theorists in the Global North. In hoping to come to terms with many of the unresolved dilemmas faced by critical theory (e.g. how to combine a critical diagnosis of existing societies with emancipatory perspectives and narrow the persistent gap between theory and praxis, philosophy and politics, abstraction and revolution), Rodríguez seeks to unite various theoretical developments of critique with the experiences of concrete social movements in the Global South. His larger aim is thus to advance a critical sociology of social movements at the crossroads of critical theory, social movement studies and empirical sociology.

To address this, Rodríguez adroitly develops his own conceptual framework from three main streams of scholarship. Firstly, influenced by Fredric Jameson, Axel Honneth and Jacques Rancière, Rodríguez builds the concept of ‘social critique as practice’—a notion bringing together the central notions of utopia, recognition and disagreement to examine the multifaceted ways in which social movements deploy their practices of critique. Secondly, based on Jameson’s notion of ‘cognitive mapping’ and Luc Boltanski’s ‘sociology of pragmatic critique’, Rodríguez explores how people’s own critical capacities can lead activists to ‘see the whole’. This orientation towards a ‘social totality’, he argues, is crucial in shaping social movements’ self-making and collective agency. Finally, trying to unite critical social theory and social movement studies, Rodríguez coins the concept of ‘critique in movement’, a term meant to capture the concrete routes by which social movements’ struggles and counter-hegemonic projects are enacted.

Resisting Neoliberal Capitalism in Chile is based on interviews conducted with leading activists among the pobladores and students and on the analysis of public documents produced by these organisations. In dialogue with the theoretical perspectives put forward, its empirical material delivers thought-provoking findings. This is the case with the pobladores social movement. Through their demands for affordable and decent housing in the councils in which they reside, Rodríguez argues that pobladores redefine themselves and the city they inhabit. From a critical diagnosis of neoliberal housing policies, their discourse moves on to articulate a critical approach to neoliberal capitalism more broadly. Although their practice of social critique is chiefly framed around a moral code rooted in poblaciones (the communities in which they are embedded), those settings are also the basis for a utopian anti-neoliberal project. ‘Our dream is bigger than a house,’ one of the interviewees puts it, giving voice to the back-and-forth movement between their local communities and the quest for ‘vida digna’ (a dignified life) or ‘el buen vivir’ (the good living) for all.

According to Rodríguez, the supports of this counter-hegemonic process can be found in the specific political strategies pobladores deploy around the ‘pre-figurative’ practices of self-management and popular education. And yet, as Rodríguez acknowledges, these practices are not devoid of strains or inconsistencies, particularly those arising from the tensions between the private ownership of housing versus a wider struggle to the right to the city for everyone.

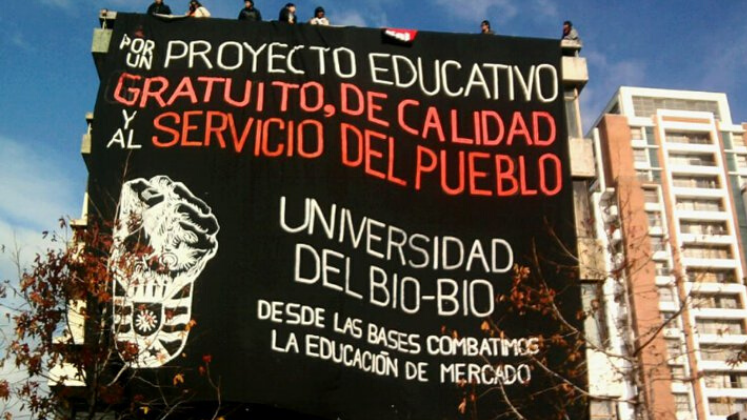

Chilean students similarly developed and mobilised a critical discourse against neoliberalism during the 2011 student protests. This critical discourse was embedded in students’ feelings of indignation towards an unequal, low-quality and highly privatised educational system, which increased access but generated a mass of debtors and thwarted dreams of upward mobility. Yet Rodríguez shows that through a growing deliberative and politicisation process enacted via local assemblies and student federations, students went beyond their identity as students and spurred a wider critique of the neoliberal political and economic arrangements governing Chilean society over the past decades.

Amply resonating with the broader population, the students’ demands revolved around public, free and high-quality education, backed by a new constitution and tax reform. ‘We are not only students but much more than that,’ says one of the student leaders interviewed. These practices and demands, Rodríguez maintains, contained the seeds of a ‘new type of citizenship’ and a ‘radical democracy’ for a post-neoliberal society. However, this possibility was not freed from the conflict between understanding education as a way to make possible the individualistic promise of social mobility and a new conception of education as a social right and as the basis for a new society.

Resisting Neoliberal Capitalism in Chile thus brings together a systematic reflection on the idea of social critique with a well-informed presentation of how the pobladores and the student movements embody critique in practice. Stretching the boundaries between a vast array of critical theorists, Rodríguez’s conceptual framework makes us rethink the practical forms of critique that social movements enact in contemporary Chile. Particularly illuminating are the applications of the theories of Jameson (‘cognitive mapping’) and Boltanski (‘social totality’), as they help us to better understand the practices enabling real social actors to make connections between different issues as well as with people and organisations beyond the initial range of their demands.

Rodríguez is compelling in showing that this orientation towards ‘totalisation’, though not bereft of tensions or contradictions, is crucial for social movements’ self-understanding and their practices of resistance and political contestation. What is at stake is not just the individual demands of specific groups but indeed Chilean society as a whole. By the same token, it is this back-and-forth movement between the concrete and the general, practised by both the pobladores and student organisations over the past years, that becomes useful to grasp the escalating nature of the social unrest currently shaking the country. In this, though not written to specifically address the reasons behind the current social crisis, Rodríguez’s book makes an important contribution.

Although stimulating in this regard, Resisting Neoliberal Capitalism in Chile also comes with some noteworthy omissions. Part of these limitations is linked to Rodríguez’s insistence on using critical theories almost exclusively arising from the Global North to make sense of the practices of social and political resistance and contestation in the Global South. But why exactly are the analytical perspectives advanced by critical theorists in the US or Europe the best manner to account for the peculiar ways of practising social critique by concrete social movements in Chile? This persistent imbalance is never addressed throughout the book.

Noticeably absent, too, is any sustained discussion of the methods used and their implications for analysis. Rodríguez does not reveal how he obtained his interview sample and the composition of it. Nor does he provide any consideration of the (dis)advantages of interviewing, as though this data-gathering technique was by default the only way to study his topic. Quite frequently, he seems to limit himself to taking his interview material at face value, without critically engaging with it. For an attempt to empirically study the concrete ways real social actors embody social critique, all this amounts to a highly disconcerting void.

These omissions show not just a striking lack of reflexivity regarding the methods and analysis undertaken—intensive interpretation about what interview statements indicate and the mobilisation of good reasons for how to use them are always necessary. They also make it harder for the reader to critically assess Rodríguez’s application of the theories invoked to interpret the empirical material presented. As a result, this ambitious book is ultimately, in my view, somewhat weakened by these drawbacks.

Still, it is promising that there are clear signs that researchers are returning to a much-needed sociology of social movements emerging from a reflexive dialogue between critical theories, social movement studies and empirical enquiry. Resisting Neoliberal Capitalism in Chile will contribute to advancing this agenda and should be welcomed for these reasons.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

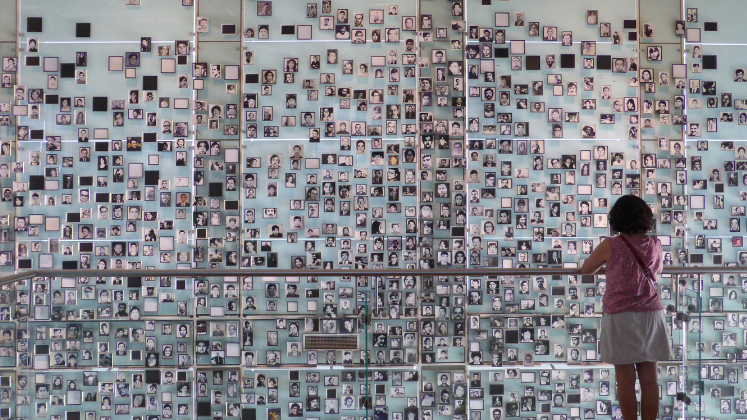

Image One Credit: Chilean Protests 2019 in Puerto Montt (North Patagonia) (Natalia Reyes Escobar CC BY SA 4.0).

Image Two Credit: Student movement protest, Chile, 2011 (Carol Crisosto Cadiz CC BY SA 2.0).