Spanning a period punctuated by landmark events from the crushing of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 to the birth of the Polish Solidarity movement in 1980 Antipolitics in Central European Art aims to anchor art historical analysis within a robust historical framework. Jim Aulich is impressed by Klara Kemp-Welch’s articulation of how small groups of artists and their audiences openly converged in a public cultural realm parallel to the intellectual and political opposition.

This book is a valuable contribution to the history of art in the second half of the twentieth century and adds to the growing literature on art from East Central Europe during the communist era. It is a detailed well-researched account of the work of representatives of an avant-gardist and non-conformist culture that refused the dominant mores of socialist realism and the state apparatuses which controlled contemporary art in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary. It is also particularly timely when, arguably, democratic institutions are under assault by forces greater than themselves in the shape of corporate power and the power of capital. Its insights and projected possibilities are drawn from a specific historical experience, which appears especially pertinent when the naked pursuit of power by those who hold it, takes precedence over the interests of those they govern. This book should be read by practising artists and everyone with an interest in what art can be, and perhaps ought to be. Think of it: an art without a market, with only the most precarious forms of distribution and dissemination, and the most marginal of audiences.

In a broadly chronological narrative Klara Kemp-Welch chooses six artists in the period 1956-89 and places them in their national and international cultural and political contexts. Her argument is structured within an analytical frame built around the concepts of ‘disinterest’; ‘doubt’; ‘dissent’; ‘humour’; ‘reticence’ and ‘dialogue’. Communism never quite succeeded in eradicating the enlightenment tradition in the region and she tells the story of artists who could never quite forget prewar national and modern forms of art and liberal individualism. She explores the strategy of ‘antipolitics’ employed by these artists to make art function as a critique of what we know, of how we can we act within a moral framework and what can we hope for through individual expression.

Largely working outside officially sanctioned institutions and producing art for relatively small circles of friends and fellow travellers on local and international levels, the controls exerted by the authorities made contemporary avant-gardist strategies amenable. These strategies, based around the body, commonplace everyday materials, the postal service, public and private spaces and minimalist interventions were broadly comparable to the Happening, and later, conceptual art in the west. They subtly distinguished themselves from these practices, not least through an awareness of the impossibility of assimilation to a market economy, and created expressive and intellectual freedoms, and degrees of absurdity and improvisation to effect and reflect social change in ways unfamiliar to the west.

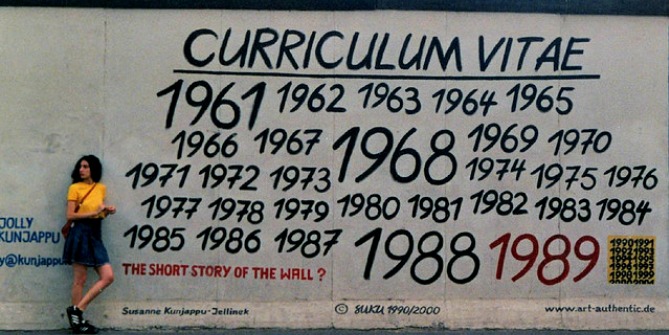

Each chapter takes a case study which is carefully positioned to be representative of important stages in the history of the region from the Warsaw Pact invasions of Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968; to the establishment of the Workers’ Defence Committee (KOR) in Poland, the Helsinki Agreement and Charter 77 in the mid-seventies, through to Solidarity and the final collapse in 1989. Briefly, the Polish artist Tadeusz Kantor (1915-90) is considered in relation to the Happening, the absurd and his commitment to artistic freedom. Julius Koller (1939-2007) from Slovakia, then part of Czechoslovakia, is examined from the point of view of his futurological speculations on the ‘ social-fascist state in a feudal atmosphere’ during the post 1968 Prague Spring period of normalisation. The Hungarian Tomas Szentjoby (b.1940) is analysed from the point of view of his poetic cut-ups, interventions and the film Centaur (1973-5) which reflected on the possibilities of labour: ‘Excuse me, is this euphoria?’ The Czech artist Jiri Kovanda (b.1953) who considered his carefully documented minimal interventions too important for politics. The conceptualist Endre Tot (b.1937) who used irony and humour to engage with the impossibility of communication in Communist Hungary and the less well-known Jerzy Beres (1930-2010) from Poland whose symbolic manifestations and religious symbolism is situated in the intellectual framework provided by Adam Michnik and Solidarity.

The term antipolitics, robust enough in its historical context, might have benefitted from some critical analysis. Antipolitics ends up looking very political, and the phenomenon benefits from Jacques Ranciere’s thinking on the nature of politics. For him, politics are unruly and oppositional, and have the capacity to interrupt the actions of the institutions of the state. Ways of being, doing and seeing are determined within what he calls a police order of what can be seen and said. In this understanding there is no place outside of this order in any society, let alone in the former communist bloc where the social and cultural order was manifestly and overtly enforced by a police state. In these conditions the party and the state determined the practices and products of art, official or unofficial. Long term legacies of socialist realism were institutionalised and embedded in the artists’ unions and the systems of art education, production, dissemination, distribution, and publication found in the galleries, exhibition spaces and even in the availability of materials and space to work in.

As a result, these art acts and manifestations were often transient, enacted by the body and aided and abetted by incidental everyday materials and environments. As disruptions they created a politics in self-realisation, even if for a brief moment. Their apparent negativity attracted the attentions of the state security and surveillance apparatuses, which it often mocked: some of the most interesting passages in the book are taken from police records. As an anarchic or anti-political stance the art brought the subject into being for artist, participant and the audience to reveal truth while simultaneously failing to provide any normative grounds or resolution. As Ranciere would have it, it is not that the art either existed for itself or that it disappeared into life: it did both, and careered between the arcane and the known, difficulty and comprehensibility, estrangement and the commonplace.

Perhaps because the practices by and large refuse politics per se, Kemp-Welch’s interpretation of the dissident intellectual climate opens up channels for further research. The armatures of her arguments such as the concept of antipolitics itself is derived from contemporary writings of the Hungarian writer and proponent of individual freedom, Gyorgy Konrad, is deployed alongside other contemporary interpretations such as the moral landscape of ‘the power of the powerless’ mapped by Vaclav Havel; Milan Kundera’s The Joke (1967); and Adam Michnik and Jacek Kuron’s political thought on self organisation and resistance in civil society. They all provide invaluable historical context while successfully ascribing to the art a sense of historical agency as it fed the paranoia of the state, but without being subjected to critical analysis themselves leave this reader wanting more.

One of the most striking aspects of the book is the digitally enhanced photography. Crisp, detailed pictures document the art discussed in the text and are an important complement to it. Yet, we do not learn how the majority were originally disseminated, if at all, or in what form. The evidence of the professional photographer Eustachy Kossakowski’s documentation of Tadeusz Kantor’s work, or the undercover photography of Jiri Kovanda’s manifestations that placed the photographer in the position of the police spy, testify in different ways that photographs were integral to the work. Contemporaneous back copies of Art International reveal badly printed, small and smudged pictures of happenings, installations and performances in the west, for example. The digital enhancement on high quality paper fetishizes and makes postmodern, they are no longer brute information or unreflective documentation. Neither do they emulate the appearance of how they originally looked as exhibited photographs or published reproductions. The observation is, perhaps, a minor point, but it would certainly bear further investigation.

For all of the persecution and harassment from the state, its patriarchialism, individualism and esoteric symbolism (often inscribed with religious and romantic undertones) contribute to a feeling of radical conservatism at the heart of the practices of art and antipolitics. This is especially the case for Kantor and Beres where, perhaps, the displacement of memories of western romantic socialist ideals onto nonconformist artists in central Europe leads to the underplaying of its religious and socially conservative elements. As Kemp Welch points out in a quotation from George Konrad’s and Ivan Szelenyi’s analysis The Intellectuals on the Road to Class Power (1979), the intelligentsia in its perception of itself as a victim absolved itself of responsibility for the functioning of the state.

These stories of anti-heroic activism are circumscribed in the introduction within a useful and nuanced discussion of dissidence. Tracing a path from critical compliance and resistance to nonconformism, civil liberties and human rights Kemp Welch articulates how small groups of artists and their audiences openly converged in a public cultural realm parallel to the intellectual and political opposition. It was a place shared with the secret police where the nonpolitical artist bypassed communist structures and engaged in a risky play with the rhetoric of state, church and official culture. Beneath the surface of this engagement with subjectivity lurked the grand narratives of national destiny, Christianity, and the romantic myth of the artist as seer were caught within a paradox defined by the materialism and authority of the police state.

Professor Jim Aulich is Head of Postgraduate Research Degrees at the Manchester School of Art. His research interests engage with the relationships between history, memory and representation, especially in the field of propaganda and publicity in the graphic arts. He was director of the ARHC funded Resource Enhancement project ‘Posters of Conflict: the visual culture of public information and counter information 1914-2005,’ a collaboration with the Imperial War Museum. Read more reviews by Jim.

3 Comments