In conflicts across the world, women continue to play a large and growing role in formal and informal military structures. Laura Sjoberg‘s book questions how useful traditional gendered categories are in understanding the dynamics of war and conflict today. Mercy Ette applauds this book for its potential to inform and influence policy on war and war-making.

In conflicts across the world, women continue to play a large and growing role in formal and informal military structures. Laura Sjoberg‘s book questions how useful traditional gendered categories are in understanding the dynamics of war and conflict today. Mercy Ette applauds this book for its potential to inform and influence policy on war and war-making.

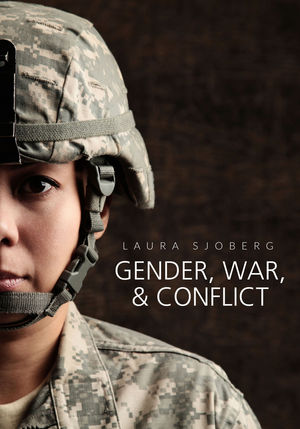

Gender, War, & Conflict. Laura Sjoberg. Polity. 2014.

Gender, War, & Conflict. Laura Sjoberg. Polity. 2014.

The conventional association of war with masculinity has many implications for women, men, and war itself, Laura Sjoberg reiterates in her new book, Gender, War, & Conflict. This is an argument she has made before but in her latest publication she adopts a broader and more critical approach in her analysis of war and gender.

To describe this book as an informative text is an understatement. It is thought-provoking, challenging, and illuminating on several levels. From the attention-grabbing personal story of Ayesha Farooq, the first female fighter pilot in the Pakistani Air Force, to a final question in the conclusion about the possible impact of gender analysis on policies about war and conflict, Sjoberg brings together textured arguments on gender roles in war and war-making. The book is a feminist international relations must-read text. Her view that gender analysis is imperative for a clear understanding of the causes, practices, and consequences of war and conflict is developed by deftly weaving together diverse examples from war and conflicts around the world and personal stories of people who have experienced conflicts of different forms.

Her objectives are twofold: firstly, to stimulate debates on gender dynamics in war and war-making, particularly in relation to International Relations; and secondly, to provide tools for gender analysis. This approach is informed by her argument that stories of war and conflict within IR tend to ignore gender by focusing mainly on political leaders, militaries, and states; a perspective that she says is not only inaccurate but cripples narratives about war and conflict. The emphasis on gender as an expression of power, social expectations, and organising principle is her attempt to rectify how war is theorised in political science and IR. She justifies this focus on the fact that ‘war is gendered, and that gender constructions are built at least in part on the dynamics of war and conflict. As such, thinking about war without gender (or gender without war) is incomplete, empirically and normatively’ (p.12). Gender, she argues, is present in the practice of war and therefore should be embedded in war theorising.

Sjoberg’s feminist perspective stimulates reflection and challenges the orthodoxy of war and conflict. In the first of several textboxes, she deftly compels readers to think about the gendered dynamics of war by summing up an account of the Chechen wars in a single paragraph with no reference to gender to illustrate how it is often omitted from war histories. She challenges common understandings of taken-for-granted concepts such as gender, war, and conflict by unpacking the assumptions associated with them. For example, the idea of war, which seems straightforward but in reality is confusing because some wars are not really wars. Think of the war on terror, or the war on drugs. The labels are misleading indeed.

Sjoberg interlaces views of other leading war and feminist theorists and scholars and weaves these into her argument to extend and enrich the discourses of war and its gendered nature. Drawing from a variety of sources and different strands of feminist, International and political science theories, Sjoberg develops tight and structured arguments about the centrality of gender in the discourses of war and conflict. With suggestions for further reading, web resources and questions at the end of each chapter, Sjoberg propels readers on a path to a deeper and broader understanding of the complex role of gender in warfare. This book provides new ways of thinking about war and conflict.

The disparity in the treatment of women and men in war narratives is a major strand in Sjoberg’s analysis. On that issue, she makes the point that women have been combatants in wars throughout history and yet are invisible in histories of war. She notes that ‘when women are recognised as fighters, their fighting is often still distinguished from men’s fighting – where men are soldiers, revolutionaries, and terrorists, women are women soldiers, women revolutionaries, and women terrorists’ (p.40, emphasis in the original). And when their presence is recognised, it is often minimised or trivialised. The centrality of gender in the discourse of war means that war stories are often about men, their exploit, their victories and their losses. In other words, war stories reflect war as a gendered institution.

A particularly interesting argument is developed in a chapter titled ‘Where are the men?’ Here, Sjoberg argues that ‘the motivational process that turns an ordinary boy or man into a reliable killer is gendered’ (p.67). This expounds Barbara Ehrenreich’s view that a transformation is required to turn an ordinary boy or man into a soldier. A key issue in this discussion is the link between masculinities and war. Contrary to dominant themes in war narratives, the roles men play in war are routinely stylised to accentuate masculinity. Put differently, only men’s roles in war that resonate with accepted masculinity are visible in war narratives but those that contradict gender expectations go untold. That explains why war stories do not emphasis the role of men as civilian victims. That label belongs to women and children.

In chapter four, Sjoberg analyses how gender plays a critical role across all dimensions of war but stresses that war is a continuum and not an event that takes place only on battlefields. Using a personal story of an Iraqi woman as a canvas, Sjoberg explores new perspectives on war and suggests a redefinition of the concept with gender at its core. Her goal is to bring about conceptual shifts in the understanding of war and gender. Such a transformation would not only result in new ways of conceptualising war but would extend to the planning and execution of war. Gender analysis, she is convinced, could change the way we see war and conflict and possibly how policy-makers practice them.

Gender, War & Conflict is not just a thought-provoking book; it is also an agenda-setting text. Sjoberg aspired to write a book that could inform and influence policy on war and war-making. She succeeded.

Mercy Ette is a senior lecturer in Journalism and Media at the University of Huddersfield, UK. She holds a Ph.D. in Communication Studies from the University of Leeds. She worked as a journalist in various positions for several years in Nigeria and in the UK. Her research focuses on journalism and conflict, media and democracy, gendered mediation, and political communication. Read more reviews by Mercy.