When Greeks and Turks Meet attempts to demonstrate how the nationalist view of relations between the two peoples is a distinctly modern one that neglects a long history of coexistence. It is an important text that will be useful to students with an interest in Turkey and Greece, as well as to those interested in the study of nationalism, writes William Eichler.

When Greeks and Turks Meet attempts to demonstrate how the nationalist view of relations between the two peoples is a distinctly modern one that neglects a long history of coexistence. It is an important text that will be useful to students with an interest in Turkey and Greece, as well as to those interested in the study of nationalism, writes William Eichler.

When Greeks and Turks Meet: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on the Relationship Since 1923. Vally Lytra (ed.). Ashgate. 2014.

When Greeks and Turks Meet: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on the Relationship Since 1923. Vally Lytra (ed.). Ashgate. 2014.

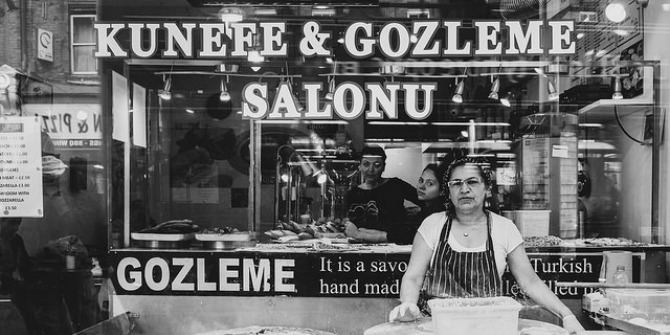

A common mistake for people from western Europe or America to make when visiting Turkey is to refer to, say, stuffed peppers as Greek. This will often be met with disapproving looks and the assertion that Greeks stole Turkish food. The use of such an accusatory verb is symptomatic of how the relationship between the two peoples is frequently conceptualised. They are viewed, and often view themselves, as natural enemies, locked in a perpetual state of conflict. When Greeks and Turks Meet seeks to advance a more nuanced picture of relations between the two peoples and to study “the relationship with the purpose of questioning essentialist representations, stereotypes and dominant myths”.

The product of a collaboration between the Centre for Hellenic Studies at King’s College London and the Turkish Studies programme at SOAS, this volume focuses on the relationship between Greeks and Turks at the personal, communal, national and transnational level. It covers a range of issues from the significance of the ‘population exchange’ for the relationship today, to the representation of the other in Greek and Turkish Cypriot schoolbooks, to Greek Orthodox minority media in Turkey. Each of the fourteen essays adopts a different disciplinary perspective, including international relations, history, sociology, anthropology, linguistics, literature, and, in one particularly interesting essay, ethnomusicology.

Dr. Vally Lytra provides the reader with some useful historical context and the theoretical framework of the book in the Introduction. 1923 marked the formal end of the conflict (1919-22) referred to in Turkey as the ‘War of Independence’ and in Greece as the ‘Asia Minor Catastrophe’. The end of hostilities was formalised on 24 July in Lausanne, but not before a “population exchange” that saw the displacement of 1.5 million people. These events prepared the ground for the founding of the Republic of Turkey (29 October) and the abandonment by Greece of its irredentist dream of dominating both sides of the Aegean. The ‘Greek inhabitants of Constantinople’ and the ‘Moslem inhabitants of Western Thrace’ were exempted from the exchange by the Convention and were assigned ‘minority status’ within their respective countries. Later, in 1960, Cyprus gained its independence from Britain, and a struggle for dominance between Greek and Turkish Cypriots ensued.

The transformation from empire to nation-states changed the nature of the relationship between Greeks and Turks. In the Ottoman Empire the two peoples had existed in close proximity to one another, in what is refered to here as ‘intercommunality’. But with the ‘unmixing of peoples’ that characterised the collapse of the empire and the emergence of modern nation-states came a situation of ‘diminished contact’. With both sides isolated from one another and hanging on to memories of 1923, fear and suspicion took over. This has provided grist for the nationalist mill and it has allowed both sides to become entrenched behind walls of nationalist mythology where the other is the enemy and the (national) self is righteous (they stole our food). This kind of binary thinking has affected mainstream scholarly research where nationalist narratives based on the “us” versus “them” dichotomy are presented as history. What unites all of the contributions to this collection is an approach that is based on a firm rejection of this tendency.

The opening chapter by social anthropologist Renee Hirschon illustrates just such an approach. Entitled “History, Memory and Emotion: The Long-term Significance of the 1923 Greco-Turkish Exchange of Populations”, it looks at the relationship at the personal, local, national and transnational levels. Studying interviews done with Greeks and Turks who experienced the “exchange”, she found there was a sense of the “common and shared experience of loss of their homeland…and a recognition of a shared culture”. As one interviewee said, “The people did not have problems between them.” Hirschon also found that Asia Minor refugees who settled in Greece attempted to deal with the disruption of being forced from their homes by recreating what they left behind. “Long-term nostalgia and the recreation of familiar places in a new space appears to be a central element in the process of adjustment.” When studied at the personal and local level then it is evident that the relationship defies any simplistic “us” versus “them” binary.

This nuance is often lacking at the national and transnational level. As noted above, 1923 marked a break between the two peoples and this ‘diminished contact’ meant that nationalist mythology could fill the breach. Hirschon writes, “The separation was reinforced by nationalistic accounts of the past…which tended to emphasise hostile relations, aggression, oppression and mutual betrayal. Estrangement was the inevitable consequence of the building of nation-state identity in which hostility towards the ‘other’ is cultivated and becomes the prevailing collective attitude.”

This chapter successfully underlines the role that nationalist ideology has played in suppressing the lived experience of individuals and creating a reductive narrative where the other is the enemy and the (national) self is virtuous. In a sentence that captures the entire message of this collection, Hirschon concludes, “It would be well for Greeks and Turks alike to delve into their common collective memories, whether pleasant or painful, and to realise how closely their worlds were intertwined for 400 years”.

When Greeks and Turks Meet is an important text which could be usefully read alongside other ‘post-nationalist’ histories, such as Umut Ozkirimli and Spyros A. Sofos’ Tormented by History: Nationalism in Greece and Turkey (2008). Both texts use comparison and interdisciplinary approaches to highlight the problems inherent within the nationalist narratives. Unlike some texts criticising nationalism in former Ottoman lands, When Greeks and Turks Meet does not romanticise the empire as a haven of multicultural peace. Instead it attempts to demonstrate how the nationalist view of relations between the two peoples is a distinctly modern one that neglects a long history of coexistence. Due to its broad disciplinary range it is a little uneven, with some essays being better than others. Overall though, it is an accomplished and accessible text that will be useful to students with an interest in Turkey and Greece, as well as to those interested in the study of nationalism.

William Eichler has a BA in Philosophy and Politics and an MA in Middle Eastern Studies. He is a freelance journalist and part-time English teacher who lives and works in the UK and Turkey. He blogs at Notes on the Interregnum: Essays and Reviews and you can follow him on Twitter at @EichlerEssays. Read more reviews by William.

You do not find these anti-Greek nationalist narratives in Turkey, what you find is indifference. While the identities of many post-Ottoman Balkan states are built on a fierce hostility to the Turks. Both the reviewer and the contributors to this volume are profoundly under-informed to treat attitudes on the the two sides as the two faces of the same coin.

Thank you for your response HR. All feed back is welcome.

You are right to point out that there is a difference between how Greece is viewed in Turkey and how Turkey is viewed in Greece. In the nationalist narratives of the Balkan states Turkey, as the progeny of the Ottoman Empire, is seen as the former imperial ruler and oppressor. In Turkey the attitude is more complex and is tied up with the republic’s complicated relationship to its Ottoman past. While historically Turkish nationalism sought to distance itself from the empire at the ideological level, the collapse of the empire still had a profound affect on the construction of a Turkish nationalist narrative. The Balkan states were seen as traitors. They were held as responsible for the empire’s collapse and as stooges of external powers (the ‘external enemy’). It was also through this lens that the Christian minorities were viewed (the ‘internal enemy’). These attitudes were carried over into the dominant Turkish nationalist narrative.

After 1923, these two opposing nationalist narratives ‘hardened’ and were perpetuated through educational institutions, national memorials etc. In Turkey Greece (as you point out) became less of an issue. In day-to-day politics today the Kurdish Question, Armenia, the EU and the Middle East are more important. Whereas in Greece Turkey is still more of an issue. This is largely because for Turkey the 1919-22 war was a triumph and for Greece is was a disaster. This difference in attitude is certainly taken into account by the contributors to “When Greeks and Turks Meet.” But this does not affect their central thesis. The “indifference” in Turkey does not mean that when any issue regarding Greece comes up (Cyprus, treatment of minorities etc.) Turkey does not view it through a nationalist paradigm because it certainly does. In fact, as I point out, even who “owns” what food is seen through a conflictual nationalist paradigm. In the Greek-Turkish relationship nationalist views of the ‘other’ may be more ‘active’ in Greece and ‘latent’ in Turkey, but, unfortunately, they are still very much alive.

It is thanks to such cross-cultural collaborative efforts as “When Greeks and Turks Meet” and the seminars and public events organised by the Centre for Hellenic Studies at King’s College London and the Turkish Studies program at SOAS under the title “Greek-Turkish Encounters”, that these nationalist narratives can be questioned and challenged.