Little Emperors and Material Girls discusses the sexual behaviour of young women in Beijing and Shanghai, and tries to draw parallels to the West. In order to deal with the lack of official statistics, Steinfeld, who worked in China as a journalist for many years, relies on interviews and personal observations. Whilst compulsively readable and entertaining, the book falls short of producing an entirely authoritative text, writes Isabel López Ruiz.

This book review has been translated into Mandarin by Chin Kai En (Mandarin LN340, teacher Lijing Shi) as part of the LSE Reviews in Translation project, a collaboration between LSE Language Centre and LSE Review of Books. Please scroll down to read this translation or click here.

Little Emperors and Material Girls: Sex and Youth in Modern China. Jemimah Steinfeld. I.B.Tauris. 2015.

Discussing sex and relationships in a country as large and diverse and China was never going to be easy. It is no surprise, therefore, that Jemimah Steinfeld’s attempt, whilst compulsively readable and entertaining, falls short of producing an entirely authoritative text. Little Emperors and Material Girls: Sex and Youth in Modern China will largely appeal to a non-specialist audience. Those looking for an academic and fully comprehensive overview of attitudes towards sexuality in the Asian giant would be better advised to look elsewhere.

Nevertheless, Steinfeld clearly knows what she is talking about. Having lived in China for several years, working as a journalist, and holding an MA in Chinese Studies from SOAS, she is well acquainted with both the theory and the reality of life in China. It will probably not change ‘the way you see China’ (unless you have been living under a rock for the past 50 years and/or hold extremely antiquated views about Asia’s largest country), but it will certainly offer you an insightful, albeit often predictable, glimpse into the minds of China’s youth.

Steinfeld does deserve some credit, as Little Emperors comes up against two very important and seemingly inevitable obstacles. Firstly, the reluctance of many interviewees to disclose details about their intimate lives. For a book that is supposedly focused on ‘Sex and Youth’, the sections concerning intimacy and sexual practices offer no surprising findings. Secondly, the lack of official statistics and information disclosed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaves the text sounding empty. Instead, Steinfeld fills the void with excessive hearsay and conjecture, resorting to friends of friends and stories she has heard about in passing. Phrases such as ‘He reported that she had said’ (161), ‘I heard about’ (170), and ‘arguments I have heard from other Chinese’ (126) only serve to discredit her arguments and leads the reader to question the factual basis of her statements.

That China’s younger generations are gradually becoming more and more ‘westernised’ should not come as a surprise to anyone. Ironically, the most interesting sections in this text concern young people’s relationships with the CCP, perhaps because the enlightening revelations about both party allegiance and divergence are backed up with reliable statistics about party membership. Nevertheless, as I read through the countless experiences of young people as they try to find who they really are and advance into adult life, I found many parallels with my own life– proof that China is not altogether as removed or different as one would think. Whether it be having to juggle family and professional commitments or the arduous search for a long-life partner, China’s youth are not even ‘Western’, they are just human.

The volume’s central section, ‘Sex and Sexuality’ dips briefly into fascinating topics before quickly dipping back out. Interviews with members of underground rock bands are awkwardly merged with discussions about safe sex and antidepressants. When discussing the issue of homosexuality in China, Steinfeld makes some questionable interpretations, comparing the 20% of Chinese people who as of 2007 believed ‘there was nothing wrong with [homosexuality]’ (141) to ‘just’ 37% of Americans who believe it is a sin. Whilst some of China’s statistics are certainly shocking, the US possibly is, in this respect, the incorrect Western counterpoint. Unwittingly, once again, Steinfeld reveals just how similar we all are.

Little Emperors is further undermined by Steinfeld’s generic statements which can be found scattered along the text. Vague sentences such as ‘China’s youth are chatting and flirting online’ (33) or ‘Promiscuity is on the rise’ (107) add nothing to her arguments, which are often hastily linked together in an effort to make each chapter flow on from each other. Not only is this disconcerting, but it also makes the text’s structure seem very artificial. Within certain sub-sections, one can also find anecdotes which quickly diverge into completely unrelated topics: For example, the life story of a gay man who cannot come out to his family suddenly turns into a discussion of China’s boarding schools.

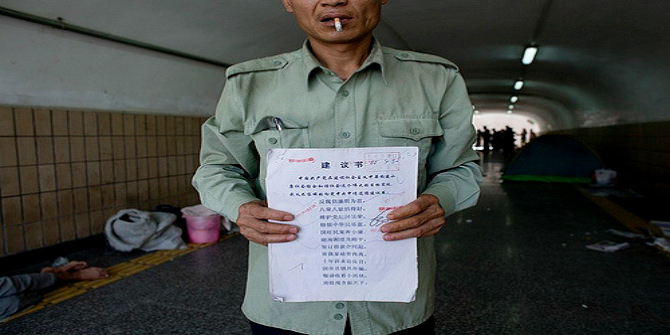

In interviewing mainly young people from either Beijing or Shanghai, arguably the country’s most ‘Westernised’ cities, Steinfeld also limits her scope to an alarming degree. In the introduction, she defends her decision to choose those who ‘were central rather than peripheral’ (8) and who ‘had the resources to participate in new cultural activities’ (7). However, I feel Little Emperors could have benefitted from contrasting points of view and a geographically broader selection of interviewees. The title of the book leads the reader to think Steinfeld will be evaluating attitudes towards sex and relationships throughout China as a whole, but this is not the case. This was disappointing, as I believe she missed out on a fantastic opportunity to explore the contrasts between different regions. Unsurprisingly, the picture painted is largely homogeneous, as Steinfeld’s interviewees all acknowledge the impact of Western trends on their day-to-day lives.

However, there is a place for Little Emperors in the current literature about China, especially with regards to its younger generations. Steinfeld’s text will definitely appeal to a mass audience and there is no doubt that many will use it as a springboard for further research. Given China’s leading role in world affairs and the growing need for intercultural communication, readers are sure to welcome Steinfeld’s volume as a small window into a very large topic.

__________________________________________________________________

Isabel López Ruiz is currently completing an MA in Twentieth-Century Literary Studies at Durham University, having previously graduated from the University of Granada (Spain) with a BA in English Language and Literature. Isabel has written articles for the Times Higher Education (both online and in print) and The Huffington Post. She also sub-edits Palatinate, Durham’s Student Newspaper. Her research interests centre on feminist literary criticism and 20th century women’s poetry, especially Sylvia Plath. She tweets at @packt_sardines. Read reviews by Isabel.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

书评:《小皇帝和拜金女:现代中国的年轻人与性》 Jemimah Steinfeld. I.B.Tauris. 2015.

Review translated by Chin Kai En (Mandarin LN340, teacher Lijing Shi).

中国是个地大物博,人口众多的国家。因此在这样一个环境下,讨论两性关系一直以来都困难重重。 斯坦菲尔德的这本书虽然引人入胜,但无法写出具有权威性的言论也在意料之中。 这本书将吸引普通读者,但那些想要更学术更全面了解中国年轻人对性的态度的专业人士最好另寻其他书籍作为参考。

中国是个地大物博,人口众多的国家。因此在这样一个环境下,讨论两性关系一直以来都困难重重。 斯坦菲尔德的这本书虽然引人入胜,但无法写出具有权威性的言论也在意料之中。 这本书将吸引普通读者,但那些想要更学术更全面了解中国年轻人对性的态度的专业人士最好另寻其他书籍作为参考。

斯坦菲尔德清楚地知道自己想传达些什么。作为一名在中国居住多年,并获得伦敦大学亚非学院中国研究的硕士学位的记者,她不仅在理论上十分了解中国,也对现实生活中的中国非常熟悉。 这本书也许不会改变你对中国的看法(除非你对中国的印象还停留在50年前那么传统,那么过时 ),可是它绝对能让你了解中国年轻一代的思想。

值得一提的是,《小皇帝和拜金女》面临两大无法逃避的考验。第一,许多采访者不愿意透露太多有关私生活的细节。对于一本专注于 “性和青春” 的书,许多关于私生活和性行为的内容不够详细,造成作者在这方面并没有太大的突破。第二,中国共产党对于官方数据和资讯的有限公开使本书的文本内容显得空洞无力。 斯坦菲尔德只好使用故事和推测来填补内容的空白,例如借用她亲朋好友的故事,及自己在过去所听到的传闻来加强她的观点。然而这些带有“他说她说过”、“我听说”、“听其他中国人说”的句子不但没有增加说服力,反而抹杀了斯坦菲尔德自己的论点,并导致读者质疑她言论的事实基础。

中国新生代渐渐被“西方化”的现象并不稀奇。讽刺的是,这篇文章最为精彩的部分竟在于描写中国青少年与中国共产党之间的关系,这也许是因为对党的忠诚和分歧的启示背后都有可靠统计数据的支撑。然而,当我阅读着无数年轻人尝试发掘真正的自我并迫不及待踏入成人世界的经历时,我从他们的经历中发现了和自己相似的故事。这证明了中国并非如一般西方人所认为的那样天差地别, 无论是兼顾家庭和事业,抑或者是对人生伴侣的苦苦追寻,中国的青少年并没有“西化”,他们只是凡人。

作为这本书的中心章节,“性以及性的特征”这个部分显得草率肤浅 。地下摇滚乐团成员的采访生硬地和安全性行为以及抗抑郁药物混为一谈。当谈到中国同性恋话题时,斯坦菲尔德的解释让人质疑 。在她比较中国人和美国人2007年对同性恋的看法时,有20%的中国人认为同性恋是正常的(141页);只有37%的美国人认为同性恋是一种罪。虽然中国的一些统计数据确实令人震惊,但美国在这方面也许无法代表西方。 不知不觉中斯坦菲尔德再次证明,“我们多么相似”。

《小皇帝和拜金女》的论点更被斯坦菲尔德过于笼统的句子削弱了。这些意义模糊的句子遍布在整篇文章内,例如:“中国的青少年在互联网上聊天和调情”(33页),“滥交正兴起”(107页)。这些句子通常匆忙地堆砌在一起,努力地使每一个章节相互呼应,但对斯坦菲尔德的论点却毫无帮助。它们非但令读者感到不舒服,而且使整个文本结构过于造作。在某些小节中,我们还可以发现具体轶事迅速偏离到毫无相关的话题,例如:从一个无法向家人坦白的同志的故事,瞬间跳跃到对中国寄宿学校的讨论。

在采访北京和上海(可以说是中国最西化的两个城市)青年时,斯坦菲尔德把范围限制到令人讶异的(狭小)程度。在引言中,她言之凿凿地辩论了为何决定选择那些 “居住在中心而不是周边的人”(08页)和 “拥有资源参与全新文化活动的人”(07页)。但是,我觉得《小皇帝和拜金女》一书更能得益于相互对比的观点以及采访更广泛的受访者。这本书的标题使读者误以为斯坦菲尔德将评估整个中国对“性和关系”的态度,但事实并非如此。这太令人失望了,因为我相信她错过了一个对比和探索不同地区之间的极好机会。不出所料,这本书的内容大同小异且毫无新意,因为所有受访者皆承认他们的日常生活受到西方文化的影响。

即便如此,《小皇帝和拜金女》在当今中国研究的文献中依然一席之地,尤其在有关中国年轻一代的方面。斯坦菲尔德的作品一定会吸引大量读者;并且毫无疑问这本书将成为未来研究的跳板。鉴于中国在全世界中的主导作用, 以及日渐增长的跨文化交流,这本书将为读者打开世界的一扇小窗。透过这扇窗,读者将看到更广阔的议题。

Find this book:

Find this book:

1 Comments