In Marching Through Suffering: Loss and Survival in North Korea, Sandra Fahy presents the oral histories of survivors of the North Korean famine of the 1990s. Fahy’s narrative outlines the origins and development of the famine, which has hitherto remained a relatively under-examined subject. Isabel López Ruiz welcomes the book for offering a compelling insight into the diverse and complex experiences and memories of survivors as well as the role of language in times of extreme struggle and hardship.

Marching Through Suffering: Loss and Survival in North Korea. Sandra Fahy. Columbia University Press. 2015.

Whilst most of the developed world was celebrating the 1990s as a decade of widespread economic prosperity – including the development of the technology industries, the creation of the World Trade Organisation and the consolidation of the European Union – North Korea was suffering from its worst famine in history. Paradoxically, despite the country being surrounded by some of the largest economies in the world, large sectors of North Korea’s population still endure famine-like conditions to this day. It is estimated that between 240,000 and 3.5 million people died of starvation or other malnutrition-related illnesses during the 1990s, and yet most people in the West are still unaware of this fact.

Whilst most of the developed world was celebrating the 1990s as a decade of widespread economic prosperity – including the development of the technology industries, the creation of the World Trade Organisation and the consolidation of the European Union – North Korea was suffering from its worst famine in history. Paradoxically, despite the country being surrounded by some of the largest economies in the world, large sectors of North Korea’s population still endure famine-like conditions to this day. It is estimated that between 240,000 and 3.5 million people died of starvation or other malnutrition-related illnesses during the 1990s, and yet most people in the West are still unaware of this fact.

In Marching Through Suffering: Loss and Survival in North Korea, Sandra Fahy takes the reader on an emotional journey through the origins and development of the North Korean famine. She interviews North Korean citizens who managed to escape their country and relocate to Seoul and Tokyo after witnessing the horrors of mass starvation. The oral testimonies of the survivors constitute the basis of this book, which is divided into chronological sections detailing every stage of the famine. From the early signs of famine in the most rural areas of North Korea, to its gradual spread throughout the country and even into the elitist capital, Pyongyang, to their escapes from almost certain deaths, the survivors recall memories of desperation and frustration.

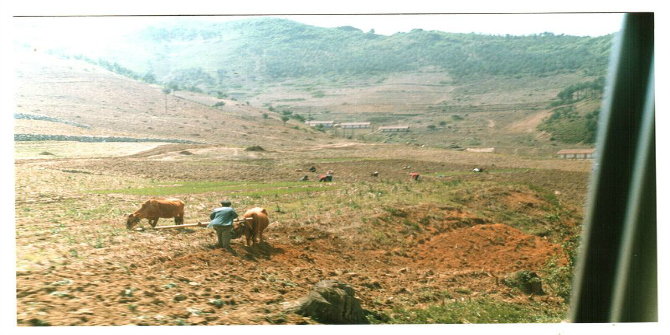

In many ways, the famine was exacerbated by the country’s rigid economic policies and reluctance to accept foreign aid, and was therefore, to an extent, man-made. Marching Through Suffering discusses the many causes of the famine, from the collapse of the Soviet Union, on which North Korea depended heavily for trade, to the floods that affected the country during the 1990s. However, when speaking to the survivors, especially those who lived in the most rural areas in the north of the country, there is a prevalent sense of frustration at the lack of available agricultural manoeuvring. Growing one’s own crops for one’s own consumption was illegal, as was selling anything on the almost non-existent black market. This drove many to rely on weeds from the most mountainous areas.

Image Credit: North Korea 1988 (Derzsi Elekes Andor)

Image Credit: North Korea 1988 (Derzsi Elekes Andor)

Whilst many books on North Korea rely on the testimonies of defectors who are heavily critical of their country’s regime, the survivors in Marching Through Suffering paint a heavily ambiguous picture. Their new lives in North Korea’s prosperous neighbours are far from idyllic. Most look back on their country fondly, recalling happier times from before the famine, but they are also tormented by their past lives and the memories of those they left behind – in many cases parents, sons and daughters. Politically speaking, most are also painfully aware of the extent to which their government deceived them, especially upon hearing about the foreign aid that should have reached them, but never made an appearance: ‘The rice which was meant for the citizens, well, it didn’t ever get sent out to the people at all, but instead was used to prepare for the war’ (Sun-ja Om, 149).

It is thus extremely refreshing to see the North Korean population being discussed not as a homogenous brainwashed mass, but rather as individuals with their own hopes, fears and reasons for escaping. Many still feel guilty about leaving, whilst others openly express their hatred for their former regime’s actions. The oral testimonies are fascinating, and Fahy’s narrative helps the reader to go beyond the survivors’ words as she discusses the purely communicative elements present in each account. She pays special attention to the significance of their chosen vocabulary – often shaped by ideological restrictions – and the importance of rumours and hearsay for the survivors as a means of understanding the situation around them. They even discuss some of the jokes that proliferated as a result of the famine, proof of their ability to adapt and find relief in times of extreme distress.

However, Fahy’s narrative, whilst largely enlightening, can sometimes strike the reader as a rather basic retelling of the survivors’ stories. Some accounts need no further explanation, so the comments that follow are often unnecessary. In addition, the book could perhaps have benefitted from an appendix that included all of the testimonies in their entirety, as the inclusion of various quotes on a single page can often become confusing. These are just small issues, however, and they make the book no less gripping.

Ultimately, Marching Through Suffering is a compelling volume that offers not only a deeply personal insight into a relatively little known episode in recent history, but also an insightful study into the language used in times of extreme struggle. The accounts of the survivors paint a vivid and multifaceted picture of the North Korean famine as well as their new lives abroad; both are much needed, given the repeated representation of the North Korean population as an oblivious, homogenous entity.

Upon completion of the book, what is most saddening is the realisation that malnutrition is still widespread in the country. Little seems to have changed, but many of the survivors still live in hope. As Mi-young Ahn explains, ‘The people are not stupid. They know the politics shouldn’t be that way; they just cannot say it. When the time comes, I think something will definitely happen’ (155).

I sincerely recommend this volume to both specialists and non-specialists in North Korean history, but it will also pique the interest of those studying speech discourse and sociology, especially personal and communal reactions to death and grief.

Isabel López Ruiz has an MA in Twentieth-Century Literary Studies (with distinction) from Durham University, having previously graduated from the University of Granada with a BA in English Language and Literature. Isabel has written articles for the Times Higher Education (both online and in print) and The Huffington Post. She has also sub-edited Palatinate, Durham University’s student newspaper. Her research interests centre on feminist literary criticism and twentieth-century US women’s poetry. She tweets at @packt_sardines. Read more reviews by Isabel López Ruiz.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.