In Angry White People: Coming Face-to-Face with the British Far Right, the investigative journalist Hsiao-Hung Pai documents conversations and encounters with members of the English Defence League (EDL) and other key figures within the British far right, supplementing this with the responses of Luton residents, anti-racist activists and Muslim communities affected by the EDL’s rise. Although James Beresford would have welcomed more detailed reflection on the methodological approach that Pai deploys in her study, this is a vital contribution to studies of far-right politics in the UK.

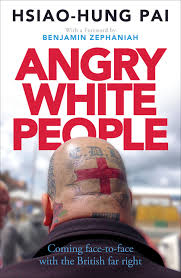

Angry White People: Coming Face-to-Face with the British Far Right. Hsiao-Hung Pai. Zed Books. 2016.

Formed around 2009, but notably brought into the public eye after the death of Lee Rigby, the English Defence League (EDL) received significant media attention until the departure of its leader Tommy Robinson (born Stephen Lennon). However, with the exception of certain academic essays and television documentaries, this focus has primarily been in the form of sporadically produced news stories that concentrate on demonstrations or particular controversies rather than a sustained examination. Ambitiously charting the movement over two years, investigative journalist Hsiao-Hung Pai importantly counters this trend with a rich, detailed account not simply of the EDL, but also of the relationships between the various people involved in or affected by it. Accessibly written, Angry White People: Coming Face-to-Face with the British Far Right documents a series of conversations and encounters that Pai experienced in Luton, the town in which the EDL was formed, and although never described directly as such, it consequently reads like an oral history of a far-right movement.

Formed around 2009, but notably brought into the public eye after the death of Lee Rigby, the English Defence League (EDL) received significant media attention until the departure of its leader Tommy Robinson (born Stephen Lennon). However, with the exception of certain academic essays and television documentaries, this focus has primarily been in the form of sporadically produced news stories that concentrate on demonstrations or particular controversies rather than a sustained examination. Ambitiously charting the movement over two years, investigative journalist Hsiao-Hung Pai importantly counters this trend with a rich, detailed account not simply of the EDL, but also of the relationships between the various people involved in or affected by it. Accessibly written, Angry White People: Coming Face-to-Face with the British Far Right documents a series of conversations and encounters that Pai experienced in Luton, the town in which the EDL was formed, and although never described directly as such, it consequently reads like an oral history of a far-right movement.

Extended quotes are commonplace throughout the book, operating like self-contained narratives. Pai provides not just a history of the movement, but also a more in-depth analysis of the implications of the EDL for individual people, and their varied relationships with it. With Angry White People somewhat resembling an ethnographic writing on space, the author spends time with those she interviews and, through going to homes or specific places in Luton, to some extent immerses herself in their everyday lives.

But while the title may give the impression that the interviewees are solely EDL members, this is not the case. Luton residents, anti-racist activists and Muslim communities victimised by the organisation are all included to provide a more holistic picture of the movement and its implications both locally and nationally. However, these long narratives are not presented in the abstract. In some instances, the stories behind the meetings and the struggles over establishing them are detailed: for example, the negotiations necessary to meet Robinson or the peculiarities of the eventual conversation with former EDL member, Darren. This isn’t simply arbitrary detail, but instead gives an insight into the dynamics of who wants to tell particular stories and the relationship that different figures have to the idea of taking up specific platforms.

Image Credit: 7 September 2013, London EDL March (David Holt)

Image Credit: 7 September 2013, London EDL March (David Holt)

Acting to situate the political project of the book, the chapters are bookended by two insightful personal reflections on racism. Linking it with her autobiography, Pai provides a very intriguing afterword in which she talks about her initial encounters with far-right activism after her migration to the UK (359-60). This is complemented and echoed by the autobiographical foreword by renowned poet Benjamin Zephaniah, recounting his experiences growing up in Birmingham and the impact that the National Front’s mobilisation had on his life (xiii-xv). What these two sections do, strategically placed before and after the main research is presented, is remind the reader of the impact such movements can have on the groups targeted.

On the face of it, Chapter Three is the most intriguing (or, at least, attention-grabbing) portion of the book, involving a somewhat in-depth interview with former EDL leader, Robinson. What turns out to be so interesting about it is not simply the importance of the figure being interviewed in the movement, but the retrospective insight that it provides. As Robinson recounts a meeting before he left the EDL, it is interesting to read his justifications for the movement when he was leading it in light of his departure. Robinson covers many of the themes and justifications that he has articulated elsewhere through various other platforms (including the abandonment of Luton and working-class people by political parties and the movement’s claimed focus on Islam rather than individual Muslims). But what is interesting is the recourse made to tropes later cited as the reason for leaving the party: mainly the presence of groups with too many associations to other movements such as the National Front or the British National Party. The reader can thus begin to trace the trajectories of the party through the narratives documented.

One of the things that is absent from the account, however, is a methodological insight. The author frames the narratives presented as a range of conversations with people that she came into contact with during the research, and on occasion comments in further detail on how these were established. However, while Pai presents a series of conversations with different‘figures involved, from anti-fascist campaigners to Muslims to EDL members, the book neither reflects on the selection process, the particular things emphasised in the encounters nor the way that they were guided by questions. What is also absent is a reflection on the politics of franchisement. On numerous occasions Pai acknowledges the racist implications of what various interviewees are saying, but does not address the ethics of reproducing this. Is this giving certain views a platform or allowing an in-depth analysis of motivations?

There is also little reflection on the validity of accounts. In Chapter Three, for example, Robinson is careful to note that he does not want to work against the police, and throughout his justifications for the EDL emphasises a focus on Islamic extremism rather than individual Muslims. Similarly, the aforementioned Darren discusses how he joined the party out of brief anger at the Muslim protests and ‘caring about Luton’, and then regretted it because he did not really understand what the EDL was (87-88). How do we know this is not a particular attempt at image management? This is especially relevant as Pai at no point talks of whether anonymity is given for ordinary members (Robinson was clearly not anonymised). Thus we do not know whether participants would feel a need to alter statements to aid public perception. However, there is still significant merit in the book, particularly given the retrospective insight and significance following the recent demise of the EDL. It thus provides an important contribution to studies of far-right politics.

James Beresford is an ESRC-funded PhD researcher in the School of Sociology and Social Policy at the University of Leeds. His research examines the construction of UK equality policies and how this relates to affect and memory.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

If you want a hilarious insight into just how clueless the author of this book is about her subject, watch this secretly recorded conversation between her and Tommy Robinson. It will give you a much better idea about whether to read her book than this review.