What is the relationship between philosophy, poetry and intoxication and should we expect ‘a sober or drunk discourse’ on the topic? Intoxication, a short reflection from Jean-Luc Nancy, explores the ambivalent pleasures of intoxication as it has been configured within histories of philosophical and poetic thought. This abundant meander through the work of Plato, Hegel and Baudelaire among others offers readers a rewarding, even intoxicating, experience, writes Bjarke Mørkøre Stigel Hansen.

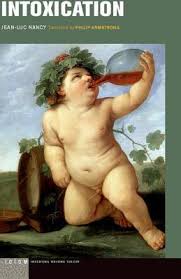

Intoxication. Jean-Luc Nancy (trans. by Philip Armstrong). Fordham University Press. 2016.

What we have before us is an address given by the French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy at an Alsatian vineyard in April 2008, in which the theme of intoxication – which one could call the ‘primal scene’ of philosophy, i.e. the question of philosophy in relation to its own origin – was brought to speech. The panegyric was subsequently published in French as Ivresse (Éditions Payout & Ravages, 2013). Under the title of Intoxication, Fordham University Press, who have taken up the admirable task of making so-called ‘French Theory’ available to its English-speaking readers, offer us Nancy’s speech in this excellent translation by Philip Armstrong.

What we have before us is an address given by the French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy at an Alsatian vineyard in April 2008, in which the theme of intoxication – which one could call the ‘primal scene’ of philosophy, i.e. the question of philosophy in relation to its own origin – was brought to speech. The panegyric was subsequently published in French as Ivresse (Éditions Payout & Ravages, 2013). Under the title of Intoxication, Fordham University Press, who have taken up the admirable task of making so-called ‘French Theory’ available to its English-speaking readers, offer us Nancy’s speech in this excellent translation by Philip Armstrong.

Intoxication, which consists of 57 humble pages (notes included), presents a piece of writing that seemingly finds itself at the margins of both text and thought, with Nancy’s discourse on intoxication touching the limit of discourse itself. The writing style of Intoxication is as drunk on its theme as it is at once subtle and inundated with poetry. For this reason, Nancy asks, ‘does philosophy get drunk on poetry? Or is it the opposite?’ Whatever the answer, Nancy continues: ‘This drinking binge or banquet has taken place since both have existed’ (6).

Imbued throughout with this question of the relation between philosophy and poetry, Intoxication attends to the distinctiveness of this dynamic that, in Nancy’s view, does not ‘constitute an opposition’, but rather moves in the direction of ‘the difficulty of making sense’ (Multiple Arts, 5). Hence, instead of constituting a relation of opposition, let alone subordination, philosophy and poetry face one another ‘in an irreconcilable mode, according to the exteriority and to an exteriority that is double qualified, since it is at once the exteriority of the phenomenon […] as being-outside-itself [that is, ecstatic and intoxicated], and the exteriority of the poetic reconciliation in relation to the thought reconciliation’ (Muses, 29). In this view, the relationship between philosophy and poetry opens up the question of intoxication to the reader inasmuch as, in Nancy’s words, ‘both desires for intoxication’ (8).

Still, the question remains as to whether we should expect a ‘sober discourse or a drunk discourse’ (4) on intoxication? For the sake of truth, is philosophy not always about sobering up in accordance with some of the central insights of the Presocratics? Indeed, Heraclitus said: ‘Whenever a man is drunk, he is lead along, stumbling, by a beardless boy; he does not perceive where he is going, because his soul is wet’ (Diels-Kranz, 117). Hence, even if ‘souls are exhaled from moist things’ (DK 12), ‘the wisest and best (most noble) soul is a dry soul’ (DK 118). Yet, as Hegel, the philosopher whom Nancy is quoting in this respect, responds in his Phänomenologie des Geistes, ‘the True is thus a Bacchanalian revel in which no member is not drunk’ (4).

Image Credit: (Kjersti Magnussen CC 2.0)

Image Credit: (Kjersti Magnussen CC 2.0)

As such, intoxication becomes the archetype for a specific strand in the history of philosophy. For what we see here is perhaps the first example of what came to be known as the Delphic injunction ‘gnothi seauton’ (‘know thyself!’) which, in Nancy’s view, forms the ‘open abyss’ (7) to be found in Plato’s dialogue The Symposium. Here, the drunken Alcibiades decides to tell the truth of Socrates, who beats everyone in drinking even though ‘no one has ever seen him drunk’ (220a). Even if we laugh at the tipsy Alcibiades, we also know from the saying that ‘truth is revealed by wine and children’ (217e). To Nancy, this is to say that truth is that which is ‘neither sought nor found, which neither proves or establishes itself; it is given […] before all donation’ (25). ‘In truth’, Nancy continues, ‘intoxication precedes all other. It is immemorial’ (7).

Thus, even though the question of the relation between philosophy and poetry – one that is itself intoxicating – concerns its very own origin set up at the drinking binge, Nancy ascribes to this primal scene a particularly significant role of intoxication as a figure, and on the threshold, of modernity. Hence, Nancy starts off from a premise taken from Charles Baudelaire’s famous collection, Paris Spleen, which serves as an ‘exergue to modernity’ (1). The premise commands: ‘You must be drunk always […] But drunk on what? On wine, on poetry, on virtue – take your pick. But be drunk.’ However, if the commandment of intoxication inscribes itself upon modernity (even if we are unable to define the beginning or end of this modernity), it is because such an inscription is the space of an exergue which, according to its numismatic character, refers to what is outside of modernity, but only to do so in terms of its inside. The commandment of modernity belongs neither to its inside nor to its outside.

The enigma of intoxication could therefore be seen in light of what has been a leitmotif throughout Nancy’s authorship – namely, the flight of gods. What would intoxication mean here? In an interview with Nancy’s friend and fellow philosopher, Jacques Derrida, it is said that drugs become the religion of atheist poets insofar as the ‘sky of transcendence comes to be emptied, and not just of Gods, but of any Other’ (The Rhetoric of Drugs, 240). Yet, if intoxication could be said to be the religion of atheists (of course, not conceived in terms of naïve atheism), we must bear in mind that this religion is not referring to a place beyond, but rather to a space of openness or excess within intoxication.

Whilst philosophy has made it its profession to sober up its spiritual ebriety, intoxication, for Nancy, does not mark an aberration from an authentic philosophical selfhood. Instead, Nancy says, even if alcohol deceives me, it cannot ‘deny that I am, I who drinks or who believes that I’m existing, whatever the liqueur. Ego sum, ego existo – ebrius I am, I exist, drunk’ (5). In this view, the liquidity of spirit – that is, the strongest liqueur spirits of wine that aim at ‘obtaining an essence, pure, the ideal, truth of a concrete and opaque and perceptible substance’ (11) – represents nothing other than ‘the perceptibility of the imperceptible’ (11). Here, intoxication does not appear as a negation of a (controlled) self; rather, intoxication becomes the index of a self and not the other way around: a non-intoxicated self is nothing special, but an intoxication where a self has evaporated into the empty sky is remarkable (‘the angel’s share’). In other words, the flight of gods that leaves the sky empty marks, as Søren Kierkegaard says, ‘the intoxicating emptiness of negativity’ (Concept of Irony, 175).

It is from this strange exergue of modernity, marked by the flight of gods, that Nancy meanders across an abundant and at times intoxicating use of poets and thinkers including Baudelaire, Mallarmé, Verlaine, Valéry, Proust, Bataille, Hegel, Hölderlin, Nietzsche and the Greeks. Although Nancy’s demanding writing requires us to start thinking ourselves, the overwhelming weight of Nancy’s ‘little’ book, if not of his ‘heavy’ thought, provides the reader with a prolific and, indeed, rewarding experience.

Bjarke Mørkøre Stigel Hansen is a PhD student in European Philosophy, European Institute at the London School of Economics and Political Science. His work explores the philosophy of Europe. He is interested in German Idealism, phenomenology and deconstruction. Read more by Bjarke Mørkøre Stigel Hansen.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.