In The House of Government: A Saga of the Russian Revolution, Yuri Slezkine offers an account of the Russian Revolution by focusing on the history of ‘The House of Government’, a Moscow apartment building built to house the revolutionary elite. While unconvinced by the book’s conclusion and some of its more meandering detours, this remains a vast, theoretically bold and innovative piece of scholarship, writes Eliot Rothwell.

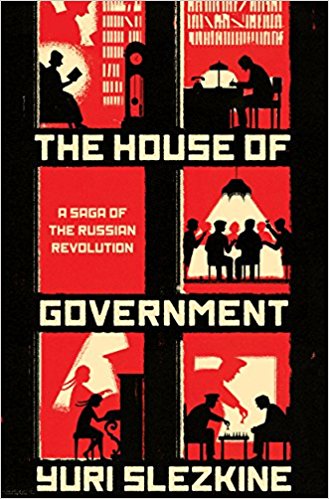

The House of Government: A Saga of the Russian Revolution. Yuri Slezkine. Princeton University Press. 2017.

Of all the books published in 2017 to coincide with the centenary of the Bolshevik Revolution, Yuri Slezkine’s The House of Government is the largest, the boldest and the most bewildering. Compromising 1128 pages, the book retells the story of the revolution as an epic family tragedy. There are echoes of Leo Tolstoy in the presentation of the cast of characters, listed in the appendix with short biographies, and the division of the work into three separate ‘books’, ending with a discussion of the dissolution of the Soviet Union. As the title suggests, this is ‘a saga of the Russian Revolution’, rather than a history.

The saga is anchored around ‘The House of Government’, an apartment building built to house the revolutionary elite. The house itself, a Constructivist block designed by Boris Iofan, remains today, located on an embankment in central Moscow, close to the Kremlin. It was built with apartments, courtyards and a vast list of amenities, including a cinema, a theatre and a social club. The first residents arrived in 1931, and eventually, by 1935, 2655 tenants occupied 505 apartments. Their lives followed the contours of the Soviet experience, through revolution, the construction of a new way of life, collectivisation, repression and war.

Slezkine draws upon the residents’ diaries, letters and published works to reveal how the larger arc of history impacted upon the minutiae of everyday life in the house. For many residents, family life was of great concern. The Podvoiskys – Nikolai, the commander in charge of storming the Winter Palace, and Nina, an editor at the Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute – agonised over how best to prepare their children for life under communism. They, like many others in the house, began to treat their biological family as the primary cell of the party. Life within and without the family was to follow the same precepts, dedicated to Lenin and the construction of communism. Questions of leisure and taste also troubled the Bolsheviks. Were rugs, ties and cologne markers of bourgeois extravagance? Mikhail Koltsov, the Pravda correspondent and Ogonyok editor, suggested they were evidence of growing material prosperity. In the house and around the rest of the Soviet Union, the reordering of everyday life occupied the minds of many Bolshevik theorists.

Image Credit: House of Government, Moscow (Ludvig14 CC BY SA 4.0)

Image Credit: House of Government, Moscow (Ludvig14 CC BY SA 4.0)

Yet, as befitting a saga, The House of Government is much more than a micro-history of the house and its residents. Slezkine’s purpose is broader. He aims to rewrite the Russian Revolution with his conception of Bolshevism and Marxism at the centre. The essential contention of the book is that the Bolsheviks were a millenarian sect, determined to bring about the end of the world. To support his theory, Slezkine analyses the writings of key figures among the Bolsheviks, demonstrating the prevalence of language tinged with religious fervour. The argument is not an original one, but Slezkine pushes it furthest. He casts Karl Marx as Jesus (114), suggests those that carried out the revolution were ‘the elect’ (36), refers to the 10th Party Congress of 1921 as ‘the Bolshevik Council of Nicaea’ and uses terms such as ‘the prophecy’ (273), ‘rites of admission’ (290) and ‘the rationalist (Calvinist) wing of the party’ (287). The point, though laboured, is clear.

Slezkine’s thesis is further inserted into the analysis of collectivisation and the Great Terror, two events which permanently marked the house and its residents. The 17th Party Congress of 1934, coming after the imposition of collectivisation, is rendered by Slezkine as the announcement that ‘the prophecy had been fulfilled’ (466). The Terror is likened to Bavarian witch trials and the Munster Anabaptists. In Slezkine’s view, the mass arrests and executions of the late 1930s evidence a millenarian sect ‘identifying and punishing heterodoxy’ (712).

But for all the insistence on millenarianism, some of the most illuminating sections on collectivisation and the Terror follow a simpler narrative. Slezkine delves into the life of Sergei Mironov, a resident of the house, NKVD director and, latterly, Ambassador to Mongolia. His time in Ukraine and Kazakhstan provides a window into the lives of those tasked with carrying out collectivisation, and the horrors they witnessed. Subsequently, centring on the house, Slezkine informs the reader that almost every child living in the House of Government was raised by a casualty of the policy, as home workers fled the countryside and took up jobs as nannies in the big cities.

Similarly, the analysis of the Terror focuses on the diaries and letters of those on trial and their closest family members. Nikolai Bukharin, a Politburo member put on trial, sent a series of letters to Joseph Stalin begging for forgiveness. Bukharin addressed the Soviet leader as ‘Koba’, an old nickname from the days of the Bolsheviks’ underground conspiracies. Before the trial, the diaries of Bukharin’s wife, Anna Larina, illustrate the frantic desperation of the family home. Bukharin refused to bathe, his two birds were dead in their cage and the ivy plant in the house had wilted. He was gaunt, pale and refused to eat. In his final letter to Stalin, before his trial and execution, he asked to see Larina and their son. Stalin never replied. Larina was later moved into the House of Government, before being sent to exile and a labour camp. She was released twenty years later, in 1953, and returned to Moscow in 1958, dedicating the rest of her life to clearing Bukharin’s name. Here, Slezkine’s family tragedy takes shape.

Further detours from the insistence on millenarianism showcase Slezkine’s skill as a writer, through forays into modernist architecture, disurbanism, socialist realist literature, the US culture wars and sexual abuse scandals in Kern County, California. The discussions illuminate Slezkine’s thinking and, quite self-consciously, demonstrate his attempt to craft a literary masterpiece anchored by ‘big ideas’. This tendency towards grand narrative and extended metaphor is evident in much of Slezkine’s earlier academic work. In The Jewish Century, published in 2004, he made the Soviet Union central to the story of Jewish life in the twentieth century but became bogged down in the larger contention that every ethnicity could be divided into two groups, ‘Apollonians’ and ‘Mercurians’. Ten years earlier, in 1994, Slezkine’s article ‘The Soviet Union as a Communal Apartment’ likened Soviet internationalism to life in a bustling kommunalka apartment, with each nationality apportioned its own slither of space.

Towards the end of The House of Government, Slezkine’s boldness runs up against the complexity of the fall of the Soviet Union. This, according to Slezkine, was precipitated by the revolution’s failure to reconfigure the family according to its own millenarian precepts. Bolshevism is considered a ‘one generation phenomenon’ (943), doomed as the children of the original believers failed to invest themselves in the prophecy. The conclusion is limited, lacking a full schematisation, and skews the book away from its central premise. It dismisses vast swathes of Soviet history and Soviet citizens, who are incorporated into the final conclusion with little analysis or historical treatment. ‘The Bolshevik Reformation’ is said to have failed, partly, as it ‘failed to convert the barbarians’ (957). The barbarians, in this schema, are the peasants or, latterly, the emerging proletarians. Yet, Slezkine presents few peasant voices and little evidence to support or dismiss his brash contention. In a book centred on the revolutionary elite, it is a strange, unnecessary conclusion to draw.

Despite these difficulties, The House of Government is a forceful piece of academic labour: vast, innovative and theoretically bold. Slezkine consults a staggering number of sources to provide a close analysis of the Revolution, the House of Government and those who came to live in it. He offers detailed discussions of the foundational events of Soviet history through the lives of the house’s residents and their close cooperators. The central thesis, though vigorously argued, will continue to be deliberated by Soviet historians, who will offer further objections to the frustrating conclusions of the final section. But, in a book that is billed as a ‘saga’ rather than a history, perhaps a degree of literary licence should be extended towards the author.

Eliot Rothwell completed his MA dissertation at UCL’s School of Slavonic and Eastern European Studies. He researched the expansion of cultural ties between the Soviet Union and Western Europe in the Khrushchev era. He also holds a BA Hons in History from the University of Warwick and spent an Erasmus year at Boğaziçi Üniversitesi in Istanbul. He tweets @EliotRothwell. Read more by Eliot Rothwell.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Find this book:

Find this book: