In Revolutionary Routines: The Habits of Social Transformation, Carolyn Pedwell examines how social change can be enacted through everyday habits and routinised practices, arguing that such ‘minor’ gestures may be just as transformative as major events. This exploration of the conditions of political possibility is an important endeavour, write Alice Menzel and Jessica Pykett, and will be of particular interest to those concerned with social justice.

Revolutionary Routines: The Habits of Social Transformation. Carolyn Pedwell. McGill-Queen’s University Press. 2021.

Find this book (affiliate link):![]()

Seemingly mundane practices and minor everyday habits are the central concern for Carolyn Pedwell’s Revolutionary Routines. In addition to her own examples of social media memes and hashtag activism (or ‘clicktivism’), we might think also of the emergence of slow fashion, the adding of gender pronouns to email signatures, the domestic routines of working fathers, the daily monitoring of air pollution or COVID-19 cases, our journey to work and the dietary choices we make. These are all types of everyday, embodied habits, or routinised practices, from which the possibility for social transformation may emerge.

Seemingly mundane practices and minor everyday habits are the central concern for Carolyn Pedwell’s Revolutionary Routines. In addition to her own examples of social media memes and hashtag activism (or ‘clicktivism’), we might think also of the emergence of slow fashion, the adding of gender pronouns to email signatures, the domestic routines of working fathers, the daily monitoring of air pollution or COVID-19 cases, our journey to work and the dietary choices we make. These are all types of everyday, embodied habits, or routinised practices, from which the possibility for social transformation may emerge.

The key premise of this thoughtful and critical text is that social change is often thought of as taking place in the ‘major’ key through large-scale political events or ‘turning points’ (11) – such as protests, revolts, upheavals and the passing of new laws/policies – and that it is their large-scale nature that is seen to grant them significance. Through Revolutionary Routines, Pedwell is interested in theorising social change as enacted through the minor key: through the everyday.

Pedwell seeks to develop a new ontology of transformation in which ‘the revolutionary and the routine are perpetually intertwined and minor gestures and tendencies may be just as significant as major events’ (6). With the rise of explicitly racist and xenophobic practices in recent years – enunciated especially through the ‘major’ political events of right-wing populism, Trumpism and Brexit – Revolutionary Routines offers a timely examination of how habits can both perpetuate and combat social injustices.

Pedwell is interested in the possibilities of everyday habits for reformulating social progress in the present, as opposed to the distant future, and the potential of habit to reinscribe social practices in the now. Pedwell’s disciplinary background in media, communications and cultural studies is evident through her emphasis on how contemporary social justice movements pursue transformation through the making of new digital ecologies. She considers how such movements reinhabit everyday spaces of digital networks and technologies to cultivate new habits and possibilities to challenge the status quo. In making this connection, the book advances a conceptualisation of habits as at once embodied, subconscious and felt as well as ‘political, institutional and datalogical’ (xix).

Image Credit: Photo by mostafa mahmoudi on Unsplash

Pedwell’s conception of habits is inspired heavily by the philosophies of speculative pragmatism, drawing particularly upon the writings of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century pragmatist philosophers John Dewey, William James and Felix Ravaisson. Their works comprise three pillars of the book’s theoretical framework, offering various ‘genealogies’ of habit. These are habits as learned phenomena which are embodied and productive (Dewey), operating below the level of consciousness (James) and repeating in a manner which offers capacity for change (Ravaisson). Reference to Erin Manning’s (2016) work on the politics of minor gestures provides a conceptual anchor to Pedwell’s central thesis on the critical importance of habit assemblages (as opposed to events, ruptures and shifts, or habits in isolation) as the source of transformation and progressive politics.

These core tenets of habits are articulated from the outset through a personal excursion into the habitual nature of sleep in the book’s preface. Reflecting upon her own experience of insomnia – and subsequent interruptions to her everyday rhythms, emotions and embodied routines (to which many readers will likely relate) – Pedwell demonstrates how habits are so routinised and automated, they become virtually unnoticeable, except during periods of disruption.

By recounting her various attempts to regain the habit of sleep, Pedwell points to the possibilities of reorientating attention away from ‘bad habits’ (after Dewey) towards more affirmative, transformative ones, noting also that affects and habits are always unstable and never fully our own. Pedwell pays critical attention to how habits mediate deeply ‘ingrained relations of privilege, power and exclusion’ (xxii) – the habit of sleep, for example, is largely driven by capitalist work routines, experienced unequally through health inequalities and minoritised ethnic groups, and (at the extreme) can even be weaponised as a form of torture. Pedwell argues that a critical politics of habit must grapple with the gendered, sexualised, racialised, classed and geopolitical dynamics of social inequalities and exclusion.

In laying out her intellectual terrain in the book’s first part, Pedwell notes the need to develop critical, contemporary re-readings of the classic works of Dewey, James and Ravaissson that are fundamental to her thesis. The book opens a philosophical conversation between pragmatist insights on habit and critical affect theory, drawing on feminist, queer, anti-racist and decolonial thinking to pay attention to the universalising assumptions of liberal theorists. Pedwell introduces a wide range of diverse thinkers grounded in a careful focus on social justice movements pertaining to racial injustice/xenophobia as well as critiques of privileged habits of whiteness. Moreover, Pedwell largely heeds Dewey’s scepticism that it is ever possible to fully imagine what a socially ‘just’ future might/should look like in advance.

At the heart of the book is a thesis on the ‘double logic’ of habit (after Ravaisson): how habits have the potential to be both transformative and stagnating. The most compelling application of this comes early in the book in Chapter Two, which focuses on racist habits and hierarchies which are deeply ingrained within neoliberal societies.

Pedwell offers an insightful comparison between white supremacy, as conscious and deliberate forms of racism, and white privilege, which is largely subconscious and habitual and thus (after Shannon Sullivan, 2006, and Sara Ahmed, 2013) unseen. Engaging with feminist, anti-racist philosophers, this chapter argues ‘racial oppression is often carried out at the habitual, embodied level through subconscious “gestures, speech, tone of voice, movement and reaction to others” (Iris Marion Young, 1990, 23)’ (65-66).

The habit of white privilege allows explicit racisms to hibernate (but not go away) and then reawaken, particularly in times of crisis. Pedwell highlights the difficulty of addressing habits of white privilege without people defaulting to defensive habits of white victimhood. She argues that exposing ‘bad’ habits is not always sufficient and can, paradoxically, reinforce inequalities; instead, she suggests that what are needed are modes of ‘undoing and unmaking’ persistent habits.

Government efforts to shape habits are the subject of Chapter Three, which examines the assumptions made by popularised ‘nudge’ techniques of governance aimed at encouraging people to change their behaviour and to make choices in their own best interest. The assumptions of these techniques and their implied ‘ideological commitments linked to patterns of socioeconomic injustice and inequality’ are questioned (86).

Pedwell guides the reader through a brief but illuminating history of the intersections between psychological knowledge and governance and problematises the notion that it is only through the breaking – rather than making – of habits that social transformation can be enacted. She situates habits as ‘the product of evolving transactions between organisms and the milieus they inhabit’ rather than as individualised behaviours (87).

So far, there seems to be little difference between the imperative to shape the choice architectures of habit formation and attempts to intervene in the structural environments which produce social injustices. But here is the crux of the issue: by re-reading behaviourism through the specific engagements of pragmatist philosophers, Pedwell draws out a key distinction.

Whilst behaviourist psychology developed theories of reflex, maladaptation and conditioning techniques, pragmatists such as Dewey advocated for the importance of human intentionality at both an individual and collective level. His idea of ‘democratic intelligence’ and promotion of transforming educational environments (95) resonate more with the normative values of recent theories of ‘boosting’ (see Mark Fabian and Jessica Pykett, 2022; Ralph Hertwig and Till Grüne-Yanoff, 2017) rather than nudging. These are based on cultivating personal and social resources for actively shaping socio-economic and political contexts through participation and enhancing capability rather than behavioural modification (107).

It is a truism to say that the media acts as an unstoppable political force, but in Chapter Four Pedwell successfully unpacks the more psychological, emotional and visual processes that shape everyday engagement with media and confirm its importance as a driver of transformative change. With reference to the tragic death of Alan Kurdi, a three-year old Syrian refugee, and the images of his body published by media outlets in 2015, Pedwell examines the potential for such images to represent, shock, amplify and move to action, or conversely to desensitise (114).

To understand the political potential of the media image, Pedwell argues, it is necessary to set out the relationships between images in addition to ‘bodies, atmospheres, infrastructures and environments’ (132). This is articulated elsewhere in recent analysis of one of the most ubiquitous images of the pandemic: expectant fathers waiting anxiously – and alone – in hospital car parks whilst their partner is in labour (Alice Menzel, 2022). The absence of fathers’ bodies in maternity care spaces illuminates specific modes of habitual (gendered) emotional governance, taken to the extreme in times of crisis through institutional restriction policies. Pedwell’s approach is useful in reminding researchers and others of the social value of the arts, imagination and cultural production in shaping not only knowledge, information and understanding, but also new political sensibilities and possible futures.

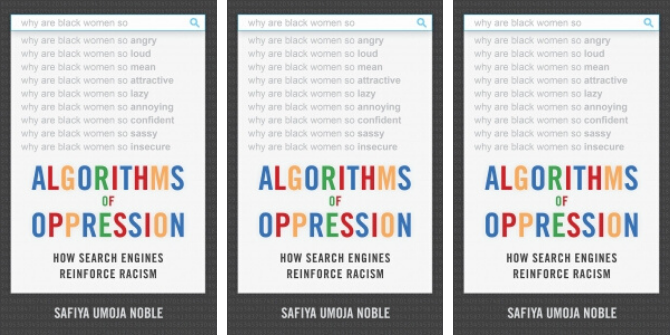

In Chapter Five on the habits of solidarity, this framework is put to work to examine the ‘progressive’ potential of habit assemblages through the examples of Black Lives Matter and Occupy activism in the US. In a careful articulation of habitual police violence and oppression of Black people and people of colour, Pedwell explores existing critiques of algorithmic biases, surveillance technologies and the deployment of digital technologies in the service of racialised capitalism (138).

Chapter Five draws attention to the radical potential of networked activisms which use the same techniques and technologies: for instance, using Twitter hashtags to create new forms of solidarity and shape community and to make visible and visceral the extent and impacts of racial oppression through online campaigning, image sharing, event organisation and international networking. Pedwell argues that Black Lives Matter exemplifies her notion of ‘“affective inhabitation”: an immersive experience that protracts our relationship with a visual image or environment, compelling us to inhabit the sensorial intensity of our encounter and its critical implications’ (144).

The inhabitation, particularly of urban space, and the limitations and boundaries set on this and experienced by Black people in the US, is a key facet of Pedwell’s ‘habit assemblage’. This spatialisation of habits is shared by both Black Lives Matter and the Occupy movement, who have collectively occupied specific places in cities to protest, to reclaim space and to enact idealised habits and routines – for example, cooking and caring together (148).

Revolutionary Routines is a quintessentially philosophical text, which offers possibilities for rethinking our understanding of the habitual nature of social oppression in its various guises. It will primarily be of interest to researchers and graduate students concerned with topics of social justice. Pedwell’s argument that such forms of prefigurative and speculative politics are as important as more strategic forms of political engagement is likely to remain a source of debate. However, her exploration of how popular culture, media, government techniques and digital ecologies are reshaping the mind, bodies and environment in ways that affect the conditions of political possibility remains an important endeavour.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.