In White Privilege: The Myth of a Post-Racial Society, Kalwant Bhopal draws on statistics and interview-based case studies to explore how Black and Minority Ethnic people in the UK and People of Colour in the US experience othering and encounter white privilege in their everyday lives, focusing particularly on education-to-work trajectories. This is a powerful critique of antidiscrimination policy that will serve as both an alarm and a call to action, writes Sinead D’Silva.

You can explore further resources on decolonisation in higher education at the Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa’s Decolonisation Hub.

White Privilege: The Myth of a Post-Racial Society. Kalwant Bhopal. Policy Press. 2018.

White Privilege is an attempt to collate various forms of evidence with a clear objective to disprove the myth of a ‘post-racial society’. Author Kalwant Bhopal offers an argument in support of the title through a critique of antidiscrimination policy by deploying an intersectional lens of analysis. The book uses statistics and interview-based case studies to shed light on the ways in which Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) people in the UK and People of Colour (PoC) in the US experience othering as they navigate everyday life that favours whiteness in both contexts. An additional layer of critique of the neoliberal knowledge economy and its inherent racism laces the book as Bhopal takes us through various stages of education-to-work trajectories to reveal how racism plays out in subtle and some not-so-subtle ways.

At the outset, we are provided with a criticism of arguments suggesting that neoliberalism negates racism, followed by an overview of the contents of the book. Chapter Two explains how whiteness and its associated privilege fit with the current contexts of Brexit in the UK and the election of Donald Trump in the USA, but also reflect a longstanding problem in British and US society. Here, we are introduced to how BME people and PoC are located within and confronted by the manifestation of whiteness in ‘Britishness’ and in the catchphrase of ‘making America great again’, alongside an attempt to make sense of the basis of white identity.

Following this, most chapters have case studies to explain their argument. Chapters Three and Four clarify who is othered from the mainstream white identity, revealing the racism faced by White Gypsy and Traveller people in the UK, and use Kimberlé Crenshaw’s notion of intersectionality to theoretically explain how BME and PoC individuals are further marginalised by other social disadvantages. Chapters Five to Eight trace manifestations of bullying and racism in different spheres from schooling to higher education, neighbourhoods, parenting and the labour market, despite the existence of antidiscrimination policies. Chapter Nine returns us to a brief overview of how these experiences of inequality relate to wealth and poverty. Finally, Chapter Ten offers some practical solutions to the problem.

White Privilege will be helpful for anyone willing to understand how white privilege manifests, as well as for those interested in addressing the problem. It is accessible and can satisfy those who want ‘evidence’ and statistics against the claim that we live in a post-racial society. Using a range of academic literature, policy documents, news articles and charity research reports as well as other data, it would not be difficult to find oneself slightly overwhelmed by the variety of sources cited. Nevertheless, Bhopal makes no excuse for focusing on the need to address this situation, and rightly so. The findings are not surprising; they are disturbing.

An aspect of the book that makes it most striking are the case studies. These give meaning to the (sometimes confusingly explained) statistics, contextualised by policy. They reveal the experiences of BME people and PoC as they come into contact with white people in neighbourhoods where they have made their homes, at school, university and at work, and serve as examples of how racial bullying and aggression manifest themselves. The narratives show that PoC and BME people, particularly those who are multiply disadvantaged, constantly have to prove their worth to the white people they meet, such as when Farah, a schoolteacher who wears a hijab, interacts with white parents. Similarly, Bernadette, an academic in a Higher Education Institution who identifies as black working-class Caribbean, has to confront racial stereotyping when interacting with colleagues in a white-dominated occupation. Through all the evidence presented, Pakistani and Bangladeshi (both largely Muslim) as well as black Caribbean women are repeatedly over-represented amongst populations of British society that experience inequality within contexts where antidiscrimination policies are said to be in place. It would have been beneficial to have case studies in all chapters with a comparable level of depth, given their importance in building the argument of the book.

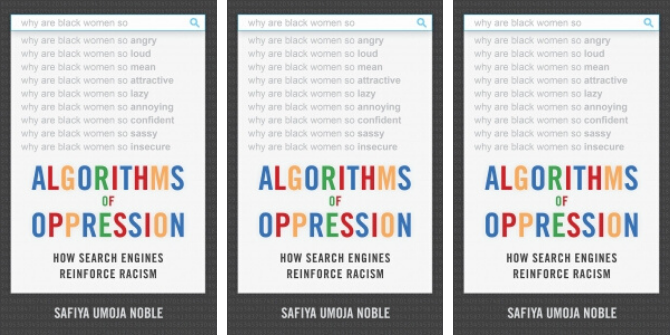

However, the focus of White Privilege is not only on BME and PoC experiences. That is a part of the story. There is a great irony as white people use defensive explanations of ‘not seeing colour’ or ‘banter’ when white privilege is identified as causing disparities. Bhopal explains this as a refusal to acknowledge historical discrimination and structural disadvantages against black people and other PoC (23, 101), which have in recent years given rise to questions like ‘Why is my curriculum white?’. This is much to the credit of the book in that it that does not merely make clear the disadvantages experienced by BME people and PoC, but locates the problem in white privilege.

The existing environment is one in which white stereotypes about minorities in society are permitted to play out, with antidiscrimination policy failing to challenge the situation: for example, by othering (indeed, victimising) Muslim children in school through arbitrary attempts to ‘prevent radicalisation’ and promote (White) ‘British values’ (74-76). This is permissible within a context that privileges a certain sense of belonging constructed along the lines of promoting whiteness. The long-terms effects of such a system, alongside the accumulation of disadvantage, serve to reproduce white privilege. In order to confront such disparities, White Privilege articulates the extent to which this practice is alive and kicking by locating it in contemporary British and US society, and offering practical solutions to address the situation, albeit largely in Higher Education. Suggestions include compulsory unconscious bias training; name-blind [sic] applications; and a quota system for BME students to Oxbridge and Russell Group universities. These sit alongside the very basic need to acknowledge the prevalence of structural racism – the book itself can assist this.

It must be mentioned that if you are looking for a detailed engagement with this problem across all spheres of society, it will be hard to find in this book. Bhopal focuses on the context of education. This relates to another aspect of White Privilege. A large portion is used to comment on discrimination in the trajectory from school to Higher Education to work, yet the book is not explicit in justifying this. There is also a slight imbalance in the national content, with the majority relating to the UK (unsurprising given the work done by the author on racial inequality in the UK). Nevertheless, the comments on the situation in the US enable us to understand both shared as well as different experiences of systematic, structural racism.

Despite the need to put the book down multiple times as it evoked my own struggles with making sense of white privilege (denial) as a PoC, I found this book appealing to my different roles and identities. As a student, I feel this book is very informative in making sense of the situation; as a researcher, the methods and sources of information are appealing; as someone engaged with policy implementation evaluation, the suggestions are very practical; as a person of colour, I feel able to recommend this book the next time I need to explain white privilege, with few questions to answer.

With solutions to offer, White Privilege is both an alarm and a call to action.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image Credit: (Golly Gforce CC BY 2.0).

Find this book:

Find this book:

4 Comments