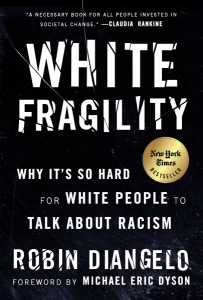

In White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism, Robin DiAngelo deftly articulates the need for white people to understand and discuss racism by showing how all white Americans share complicity in maintaining racism as the bedrock of US society. The book should encourage white people to intentionally take steps in their own lives to dismantle white supremacy, confront white privilege and deconstruct the racist structures that underpin society, writes Chelsey Dennis.

White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism. Robin DiAngelo. Beacon Press. 2018.

In response to the increasingly polarised ideological climate in the United States, Robin DiAngelo deftly articulates the need for white people to understand and discuss racism. Her book, White Fragility, comes at a time when the topic of racism does make its way into dinner conversations, political debates, social media posts and newspaper headlines. However, most of these discussions are premised on the widely held belief that racism is only perpetuated by individual people in individual situations who show prejudice towards a person of colour. DiAngelo masterfully explains how this definition of racism is harmfully limiting and flat-out wrong. Her book clearly lays out how racism is the bedrock of American society and how all white Americans are holding it in place.

In response to the increasingly polarised ideological climate in the United States, Robin DiAngelo deftly articulates the need for white people to understand and discuss racism. Her book, White Fragility, comes at a time when the topic of racism does make its way into dinner conversations, political debates, social media posts and newspaper headlines. However, most of these discussions are premised on the widely held belief that racism is only perpetuated by individual people in individual situations who show prejudice towards a person of colour. DiAngelo masterfully explains how this definition of racism is harmfully limiting and flat-out wrong. Her book clearly lays out how racism is the bedrock of American society and how all white Americans are holding it in place.

The term ‘white fragility’ was coined by DiAngelo in her 2011 article by the same name, published in The International Journal of Critical Pedagogy. White fragility refers to the intense emotions, the defensive stance and the argumentation white people experience, take and utilise when confronted with the topic of racism. DiAngelo gives many examples of white fragility, from her own experiences to those that she has observed in her job as a consultant on racial and social justice issues. One common example of white fragility is a white man who insists that white people are being discriminated against because of affirmative action. Another example is a woman of colour who claims a white woman is speaking over her; in response, the white woman says she speaks over everyone, therefore it is not a race issue. Other examples illustrate white fragility at a national level, such as the Black Lives Matter movement being contorted into ‘All Lives Matter’ by white people who feel threatened. Or the anxiety white people develop at the thought of being the minority (which studies indicate will be the case in America by 2044). White fragility also manifests in anti-immigration policies by President Donald Trump’s administration, as shown in the travel ban on people from majority Muslim countries. By the last chapter, most readers will not question what white fragility looks like as a result of the thorough and diverse examples provided by DiAngelo: it is present in innumerable situations and interactions that are seen and heard by most Americans on a daily basis.

DiAngelo skillfully walks the reader through many elements of white fragility. She provides a history of racism starting with colonialism. As white Europeans usurped indigenous peoples’ land around the world, colonisers needed a reason to justify treating indigenous people of colour as less than human, and so racism and white supremacy were born. DiAngelo dedicates a lot of the book to explaining this history to show the reader how race is a social construct rather than a biological one. She provides examples of how early Americans, like Thomas Jefferson, advocated for biological differences: ‘Jefferson suggested that there were natural differences between the races and asked scientists to find them’ (16). DiAngelo discusses how this history justified and propelled the transatlantic slave trade, American slavery, the Jim Crow South and today’s racism following the Civil Rights era and the fallacy of a so-called ‘post-racial’ America.

DiAngelo devotes Chapter Three of White Fragility to this later history, showing how racism was shaped after the American Civil Rights era of the 1950s and 1960s. During the Civil Rights movement, some white people’s ideas of racism began to change. Before this time, it was socially acceptable in certain parts of America to openly discriminate against people of colour. However, after the white middle class watched peaceful protestors get ambushed and people of colour being attacked on television, such as during the 1961 Freedom Rides, ideas shifted, social norms changed, and in 1964 the Civil Rights Act became law. After this, it was less acceptable to be prejudiced in public. Thus, DiAngelo argues, open racism made a person ‘bad’, while appearing to treat everyone equally meant a person was perceived as ‘good’.

Indeed, one of the reasons that white people have such a hard time discussing race in any form, DiAngelo suggests, is precisely because of what she calls the ‘good/bad binary’. Based on the horrific scenes that white Americans saw during the Civil Rights movement, the meaning of racism went through a transformation. Suddenly, racism was perceived as evil and only perpetuated by bad people through individual acts of violence. Hence, if a white person is called racist now, they take personal offence because they equate it with being called a horrible person. DiAngelo argues that this is one of the pillars holding white fragility in place and, ultimately, systemic racism and white supremacy. Every white person has racial biases and, through complicity and sensibility, holds up the structure of racism. As DiAngelo explains:

If we cannot discuss these dynamics or see ourselves within them, we cannot stop participating in racism. The good/bad binary made it effectively impossible for the average white person to understand— much less interrupt— racism (72).

Another significant part of today’s oppression is holding whiteness as the norm. Most white people do not see ‘white’ as a race because most only value white culture and traditions. This normative whiteness is on display virtually everywhere: ‘’‘flesh colored’’ makeup, standard emoji, depictions of Adam and Eve, Jesus and Mary, education models of the human body with white skin and blue eyes’ (57). Whiteness, then, becomes the benchmark against which all other races are measured. Accordingly, most white people do not acknowledge their whiteness and they develop a particular sensibility around the topic of race and try to avoid talking about it. The book illustrates this by describing a mother’s horror when her daughter points out a black man’s skin in public; DiAngelo suggests that if the daughter had pointed out white skin, it would not have been shocking to the mother.

DiAngelo describes many of the structures and systems in America that have held people of colour down and have, conversely, afforded white people many privileges. She holds the far right, the left and everyone in between at fault. In addressing people who consider themselves ‘progressive’, she discusses adverse racism: ‘a manifestation of racism that well intentioned people who see themselves as educated and progressive are more likely to exhibit […for example] rationalising racial segregation as unfortunate but necessary to access ‘‘good schools’’ (43).

She does not shy away from any topic or any type of person, including herself. DiAngelo has been on a long journey, trying to dismantle her own white fragility and racism. She provides a vignette detailing a recent example of speaking with one of her black colleagues, Angela. In a meeting with Angela, she made a comment that made Angela feel uncomfortable and chose to repair the harm and learn from the experience: ‘I open by asking Angela ‘‘Would you be willing to grant me to repair the racism I perpetrated towards you?’’ […] she agrees. ‘‘I realize my comment about Deborah’s hair was inappropriate.’’ Angela nods and explains she did not know me and did not want to be joking about a black woman’s hair’ (40). She continues with their detailed conversation about moving forward. This vignette gives the reader insight into what their own journey could look like and makes this process tangible.

This groundbreaking book ends as DiAngelo provides ways that other white people can work on their own white fragility and racism. She notes: ‘Interrupting racism takes courage and intentionality, the interruption is by definition not passive or complacent […] I offer that we must never consider ourselves finished with our learning’ (153). DiAngelo relates this work to a continuum:

I have found it much more useful to think of myself as on a continuum. Racism is so deeply woven into the fabric of our society that I do not see myself escaping from that continuum in my lifetime. But I can continually seek to move further along it […This idea] changes the question from whether I am or am not racist to […] am I actively seeking to interrupt racism in this context?

While DiAngelo does make references to other countries and acknowledges that ‘white supremacy is especially relevant in countries that have a history of colonialism by western nations’ (29), White Fragility ultimately focuses on white supremacy and racism as it exists in the United States. This may leave the reader wanting more analysis of how white fragility may be revealed in other countries; this limitation of scope also results in the book resonating most strongly with an American audience.

White Fragility therefore offers white American readers a window into the white supremacist society that they have been complicit in building, brick-by-brick. It is time for white people to intentionally and methodically take steps in their own lives to dismantle the white supremacy and racist structures that persist. Reading this book is an essential step in seeking to move further along the continuum. Whether you are a white scholar, nanny, lawyer, waitress, teacher or engineer, we all live in this broken system that holds up white supremacy and racism, and it is our job to work towards fixing it.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image Credit: (Alan Levine CC BY 2.0).

This book makes me cringe with its terribly flawed logic. As a progressive I am embarrassed this has become a best seller, no wonder the right is laughing at us.