In Brexit and Beyond: Rethinking the Futures of Europe, editors Benjamin Martill and Uta Staiger bring together contributors to consider the possible implications of Brexit for the futures of Europe and the European Union. Available to download here, the book’s interdisciplinary approach makes clear the difficulties of predicting the potential outcomes of an unfolding process while nonetheless outlining a number of different scenarios and possibilities in detail, writes Anna Nadibaidze.

Brexit and Beyond: Rethinking the Futures of Europe. Benjamin Martill and Uta Staiger (eds). UCL Press. 2018.

With a deal on the post-Brexit transition period agreed in March, the UK and the European Union are getting closer towards building a framework for their new political, economic and security relationship. At the same time, both the process and consequences of Brexit remain complex and uncertain: as negotiators on both sides say, ‘nothing is agreed until everything is agreed.’

The difficulties of analysing the process and possible outcomes of Brexit are captured in Brexit and Beyond: Rethinking the Futures of Europe. The volume is a collection of short analytical essays that has for its main goal an examination of ‘the likely effects of Brexit for the futures of Europe and the EU’ (3). It points out that ‘neither the causes nor the consequences of Brexit can be adequately understood solely within the confines of the British state’ and that the UK’s departure is ‘of great significance for the future of Europe’ (260).

Acknowledging that Brexit is a unique phenomenon that needs to be examined from a multidimensional perspective and given the vast number of challenges that the EU27 need to address during the transition period and beyond, the editors make the case for an interdisciplinary approach. The first part of the book focuses on the impact of Brexit on actors including the UK, EU institutions and member states such as Germany, France and Ireland. The second part explores the effects of Brexit on various areas and policies, such as Europe’s political economy, legal and judicial issues, foreign and security policy and democratic legitimacy, and also offers a general evaluation of the future of Europe. Overall, five main questions are addressed: 1) How representative is Brexit?; 2) How do we define European integration?; 3) How to understand the crises that the EU is going through?; 4) What is the status of sovereignty and democracy in today’s globalised world?; and 5) What is the future of the EU after Brexit?

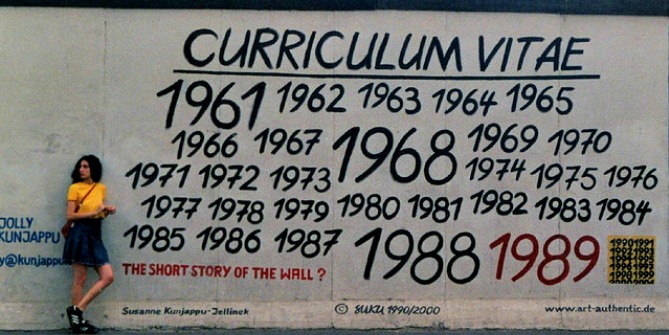

Image Credit: (Robyn Mack CC BY 2.0)

Image Credit: (Robyn Mack CC BY 2.0)

With regards to the last question, the authors and editors seem to agree that the effects of the UK’s departure on Europe will be significant, but the volume is not for those who expect a specific prediction of Brexit’s outcomes. Rather, a variety of possible developments is presented through different lenses. In terms of future consequences for the European economy, Waltraud Schelkle writes that the relocation of financial services from the City of London to the Euro area is likely to cause changes to the Eurozone’s regulatory approach and a strengthening of the euro in relation to the pound. Meanwhile, Christopher Bickerton warns that Brexit is just the tip of an iceberg of wider trends of discontent towards both European economic integration and national economic growth models. Elsewhere, Abby Innes points to a ‘crisis of ungovernability’ in the EU, caused by the pro-market reforms of the last thirty years.

In the field of legal and judicial issues, Deirdre Curtin assesses the options for future data-sharing arrangements between the UK and the EU, pointing out that while there is no precedent for the kind of deep partnership London is asking for, Brussels has been able to find flexible solutions before, as in the case with Denmark. Jo Shaw analyses the impacts on free movement, as well as the need to reassess the meaning of both national and European citizenship.

The future UK-EU relationship will also have an effect on European foreign and security policies. Amelia Hadfield points out that there are many formal and informal ways in which the UK can continue to be involved in European mechanisms while also seeking to be an independent ‘Global Britain’, and these interactions will have an effect on the future of European security. As Christopher Hill argues, the UK may not necessarily be ‘welcomed back to the centre of [EU] discussions’ on foreign policy (192). This could, for instance, lead the way for stronger Franco-German leadership in this sphere.

Last but not least, Brexit has important consequences for the future of the idea of the European Union, particularly the legitimacy of EU institutions. Euroscepticism is not a phenomenon exclusive to the UK. Many national election results suggest that citizens across the continent expect reforms at the EU level and an open debate on European policies. As Michael Shackleton observes, the EU27 will not ‘have the luxury, even if they had the desire, to stand still’ (204). Brexit has acted as a trigger for European leaders to search for a common post-Brexit European identity, produce visible and tangible benefits for citizens in the form of public goods and enable people to have a more direct role in EU politics.

The volume also puts forward a number of suggestions for the future of the EU, the changing nature of the EU27 and how European institutions could be modified in order to address the feeling that ‘something is rotten in Europe’ (10). Kalypso Nicolaïdis’s idea of ‘sustainable integration’ is one such proposal. She defines it as a ‘durable ability to sustain cooperation’ in the EU in the long term, a necessary change to make after Brexit in order to reshape a Union of which citizens want to be a part (213). In another chapter, Simon Hix suggests a model of ‘decentralised federalism’ for the EU: essentially a trade-off where member states would grant more competences to supranational institutions in some policy areas, while ‘granting a high degree of flexibility and discretion to the states in the application of central rules’ (78).

Elsewhere, Luuk van Middelaar urges the EU to show its commitment to protecting its citizens by finding a balance between providing economic freedoms and social protection in order to reassure both those who value the opportunities given by the EU and those who fear the ‘disorder and disruptions that the EU creates in terms of migration, competition for jobs, or the loss of national sovereignty’ (84).

Overall, while there is an agreement among contributors and editors that Brexit has served as a wake-up call that has encouraged an open public debate about the future of the EU, the diversity of the suggestions proposed in Brexit and Beyond demonstrates that there are many options on the table on how to move forward. This volume is also a good example of how comprehensive discussions can take place in an accessible format, not only in terms of its structure, but also as it is available to download for free, which opens the debate to the non-academic community as well.

From the time of the publication of Brexit and Beyond until now, much has already changed and much has already become outdated. As the editors admit: ‘Studying Brexit is like tracking a moving target’ (263). However, the book still fulfills its goal of demonstrating that Brexit has been a critical juncture for scholars and policymakers to ‘rethink the futures of Europe’, while exploring different types of scenarios and options, some of which have not been discussed before.

Anna Nadibaidze holds an MSc in International Relations from the LSE and has previously studied at McGill University and the University of Edinburgh. Her research interests include European and Russian/Eurasian politics, international institutions, and discourse in IR. She tweets: @AnnaRNad. Read more by Anna Nadibaidze.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Find this book:

Find this book:

7 Comments